Toxic Heavy Metal

A toxic heavy metal is any relatively dense metal or metalloid that is noted for its potential toxicity, especially in environmental contexts. The term has particular application to cadmium, mercury and lead, all of which appear in the World Health Organization's list of 10 chemicals of major public concern. Other examples include manganese, chromium, cobalt, nickel, copper, zinc, silver, antimony and thallium.

Heavy metals are found naturally in the earth. They become concentrated as a result of human caused activities and can enter plant, animal, and human tissues via inhalation, diet, and manual handling. Then, they can bind to and interfere with the functioning of vital cellular components. The toxic effects of arsenic, mercury, and lead were known to the ancients, but methodical studies of the toxicity of some heavy metals appear to date from only 1868. In humans, heavy metal poisoning is generally treated by the administration of chelating agents. Some elements otherwise regarded as toxic heavy metals are essential, in small quantities, for human health.

Contamination sources

Heavy metals are found naturally in the earth, and become concentrated as a result of human activities, or, in some cases geochemical processes, such as accumulation in peat soils that are then released when drained for agriculture. Common sources are mining and industrial wastes; vehicle emissions; lead-acid batteries; fertilisers; paints; treated woods; aging water supply infrastructure; and microplastics floating in the world's oceans. Arsenic, cadmium and lead may be present in children's toys at levels that exceed regulatory standards. Lead can be used in toys as a stabilizer, color enhancer, or anti-corrosive agent. Cadmium is sometimes employed as a stabilizer, or to increase the mass and luster of toy jewelry. Arsenic is thought to be used in connection with coloring dyes. Regular imbibers of illegally distilled alcohol may be exposed to arsenic or lead poisoning the source of which is arsenic-contaminated lead used to solder the distilling apparatus. Rat poison used in grain and mash stores may be another source of the arsenic.

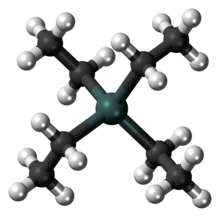

Lead is the most prevalent heavy metal contaminant. As a component of tetraethyl lead, (CH

3CH

2)

4Pb, it was used extensively in gasoline during the 1930s–1970s. Lead levels in the aquatic environments of industrialised societies have been estimated to be two to three times those of pre-industrial levels. Although the use of leaded gasoline was largely phased out in North America by 1996, soils next to roads built before this time retain high lead concentrations. Lead (from lead(II) azide or lead styphnate used in firearms) gradually accumulates at firearms training grounds, contaminating the local environment and exposing range employees to a risk of lead poisoning.

Entry routes

Heavy metals enter plant, animal and human tissues via air inhalation, diet, and manual handling. Motor vehicle emissions are a major source of airborne contaminants including arsenic, cadmium, cobalt, nickel, lead, antimony, vanadium, zinc, platinum, palladium and rhodium. Water sources (groundwater, lakes, streams and rivers) can be polluted by heavy metals leaching from industrial and consumer waste; acid rain can exacerbate this process by releasing heavy metals trapped in soils. Transport through soil can be facilitated by the presence of preferential flow paths (macropores) and dissolved organic compounds. Plants are exposed to heavy metals through the uptake of water; animals eat these plants; ingestion of plant- and animal-based foods are the largest sources of heavy metals in humans. Absorption through skin contact, for example from contact with soil, or metal containing toys and jewelry, is another potential source of heavy metal contamination. Toxic heavy metals can bioaccumulate in organisms as they are hard to metabolize.

Detrimental effects

Heavy metals "can bind to vital cellular components, such as structural proteins, enzymes, and nucleic acids, and interfere with their functioning". Symptoms and effects can vary according to the metal or metal compound, and the dose involved. Broadly, long-term exposure to toxic heavy metals can have carcinogenic, central and peripheral nervous system, and circulatory effects. For humans, typical presentations associated with exposure to any of the "classical" toxic heavy metals, or chromium (another toxic heavy metal) or arsenic (a metalloid), are shown in the table.

| Element | Acute exposure usually a day or less |

Chronic exposure often months or years |

| Cadmium | Pneumonitis (lung inflammation) | Lung cancer Osteomalacia (softening of bones) Proteinuria (excess protein in urine; possible kidney damage) |

| Mercury | Diarrhea Fever Vomiting |

Stomatitis (inflammation of gums and mouth) Nausea Nephrotic syndrome (nonspecific kidney disorder) Neurasthenia (neurotic disorder) Parageusia (metallic taste) Pink Disease (pain and pink discoloration of hands and feet) Tremor |

| Lead | Encephalopathy (brain dysfunction) Nausea Vomiting |

Anemia Encephalopathy Foot drop/wrist drop (palsy) Nephropathy (kidney disease) |

| Chromium | Gastrointestinal hemorrhage (bleeding) Hemolysis (red blood cell destruction) Acute renal failure |

Pulmonary fibrosis (lung scarring) Lung cancer |

| Arsenic | Nausea Vomiting Diarrhea Encephalopathy Multi-organ effects Arrhythmia Painful neuropathy |

Diabetes Hypopigmentation/Hyperkeratosis Cancer |

History

The toxic effects of arsenic, mercury and lead were known to the ancients but methodical studies of the overall toxicity of heavy metals appear to date from only 1868. In that year, Wanklyn and Chapman speculated on the adverse effects of the heavy metals "arsenic, lead, copper, zinc, iron and manganese" in drinking water. They noted an "absence of investigation" and were reduced to "the necessity of pleading for the collection of data". In 1884, Blake described an apparent connection between toxicity and the atomic weight of an element. The following sections provide historical thumbnails for the "classical" toxic heavy metals (arsenic, mercury and lead) and some more recent examples (chromium and cadmium).

Arsenic

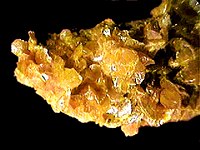

Arsenic, as realgar (As

4S

4) and orpiment (As

2S

3), was known in ancient times. Strabo (64–50 BCE – c. AD 24?), a Greek geographer and historian, wrote that only slaves were employed in realgar and orpiment mines since they would inevitably die from the toxic effects of the fumes given off from the ores. Arsenic-contaminated beer poisoned over 6,000 people in the Manchester area of England in 1900, and is thought to have killed at least 70 victims. Clare Luce, American ambassador to Italy from 1953 to 1956, suffered from arsenic poisoning. Its source was traced to flaking arsenic-laden paint on the ceiling of her bedroom. She may also have eaten food contaminated by arsenic in flaking ceiling paint in the embassy dining room. Ground water contaminated by arsenic, as of 2014, "is still poisoning millions of people in Asia".

Mercury

The first emperor of unified China, Qin Shi Huang, it is reported, died of ingesting mercury pills that were intended to give him eternal life. The phrase "mad as a hatter" is likely a reference to mercury poisoning among milliners (so-called "mad hatter disease"), as mercury-based compounds were once used in the manufacture of felt hats in the 18th and 19th century. Historically, gold amalgam (an alloy with mercury) was widely used in gilding, leading to numerous casualties among the workers. It is estimated that during the construction of Saint Isaac's Cathedral alone, 60 workers died from the gilding of the main dome. Outbreaks of methylmercury poisoning occurred in several places in Japan during the 1950s due to industrial discharges of mercury into rivers and coastal waters. The best-known instances were in Minamata and Niigata. In Minamata alone, more than 600 people died due to what became known as Minamata disease. More than 21,000 people filed claims with the Japanese government, of which almost 3000 became certified as having the disease. In 22 documented cases, pregnant women who consumed contaminated fish showed mild or no symptoms but gave birth to infants with severe developmental disabilities. Since the industrial Revolution, mercury levels have tripled in many near-surface seawaters, especially around Iceland and Antarctica.

Lead

The adverse effects of lead were known to the ancients. In the 2nd century BC the Greek botanist Nicander described the colic and paralysis seen in lead-poisoned people. Dioscorides, a Greek physician who is thought to have lived in the 1st century CE, wrote that lead "makes the mind give way". Lead was used extensively in Roman aqueducts from about 500 BC to 300 AD. Julius Caesar's engineer, Vitruvius, reported, "water is much more wholesome from earthenware pipes than from lead pipes. For it seems to be made injurious by lead, because white lead is produced by it, and this is said to be harmful to the human body." During the Mongol period in China (1271−1368 AD), lead pollution due to silver smelting in the Yunnan region exceeded contamination levels from modern mining activities by nearly four times. In the 17th and 18th centuries, people in Devon were afflicted by a condition referred to as Devon colic; this was discovered to be due to the imbibing of lead-contaminated cider. In 2013, the World Health Organization estimated that lead poisoning resulted in 143,000 deaths, and "contribute[d] to 600,000 new cases of children with intellectual disabilities", each year. In the U.S. city of Flint, Michigan, lead contamination in drinking water has been an issue since 2014. The source of the contamination has been attributed to "corrosion in the lead and iron pipes that distribute water to city residents". In 2015, the lead concentration of drinking water in north-eastern Tasmania, Australia, reached a level over 50 times the prescribed national drinking water guidelines. The source of the contamination was attributed to "a combination of dilapidated drinking water infrastructure, including lead jointed pipelines, end-of-life polyvinyl chloride pipes and household plumbing".

Chromium

Chromium(III) compounds and chromium metal are not considered a health hazard, while the toxicity and carcinogenic properties of chromium(VI) have been known since at least the late 19th century. In 1890, Newman described the elevated cancer risk of workers in a chromate dye company. Chromate-induced dermatitis was reported in aircraft workers during World War II. In 1963, an outbreak of dermatitis, ranging from erythema to exudative eczema, occurred amongst 60 automobile factory workers in England. The workers had been wet-sanding chromate-based primer paint that had been applied to car bodies. In Australia, chromium was released from the Newcastle Orica explosives plant on August 8, 2011. Up to 20 workers at the plant were exposed as were 70 nearby homes in Stockton. The town was only notified three days after the release and the accident sparked a major public controversy, with Orica criticised for playing down the extent and possible risks of the leak, and the state Government attacked for their slow response to the incident.

Cadmium

Cadmium exposure is a phenomenon of the early 20th century, and onwards. In Japan in 1910, the Mitsui Mining and Smelting Company began discharging cadmium into the Jinzugawa river, as a byproduct of mining operations. Residents in the surrounding area subsequently consumed rice grown in cadmium-contaminated irrigation water. They experienced softening of the bones and kidney failure. The origin of these symptoms was not clear; possibilities raised at the time included "a regional or bacterial disease or lead poisoning". In 1955, cadmium was identified as the likely cause and in 1961 the source was directly linked to mining operations in the area. In February 2010, cadmium was found in Walmart exclusive Miley Cyrus jewelry. Wal-Mart continued to sell the jewelry until May, when covert testing organised by Associated Press confirmed the original results. In June 2010 cadmium was detected in the paint used on promotional drinking glasses for the movie Shrek Forever After, sold by McDonald's Restaurants, triggering a recall of 12 million glasses.

Remediation

2[CaEDTA] to give Na

2[PbEDTA], which is passed out of the body in urine.

In humans, heavy metal poisoning is generally treated by the administration of chelating agents. These are chemical compounds, such as CaNa2 EDTA (calcium disodium ethylenediaminetetraacetate) that convert heavy metals to chemically inert forms that can be excreted without further interaction with the body. Chelates are not without side effects and can also remove beneficial metals from the body. Vitamin and mineral supplements are sometimes co-administered for this reason.

Soils contaminated by heavy metals can be remediated by one or more of the following technologies: isolation; immobilization; toxicity reduction; physical separation; or extraction. Isolation involves the use of caps, membranes or below-ground barriers in an attempt to quarantine the contaminated soil. Immobilization aims to alter the properties of the soil so as to hinder the mobility of the heavy contaminants. Toxicity reduction attempts to oxidise or reduce the toxic heavy metal ions, via chemical or biological means into less toxic or mobile forms. Physical separation involves the removal of the contaminated soil and the separation of the metal contaminants by mechanical means. Extraction is an on or off-site process that uses chemicals, high-temperature volatization, or electrolysis to extract contaminants from soils. The process or processes used will vary according to contaminant and the characteristics of the site.

Benefits

Some elements otherwise regarded as toxic heavy metals are essential, in small quantities, for human health. These elements include vanadium, manganese, iron, cobalt, copper, zinc, selenium, strontium and molybdenum. A deficiency of these essential metals may increase susceptibility to heavy metal poisoning.

See also

- Bento Rodrigues dam disaster

- Heavy metal detoxification

- Kingston Fossil Plant coal fly ash slurry spill

- Light metal

- Metal toxicity

Notes

- ^ Up to one-sixth of China's arable land might be affected by heavy metal contamination.

Citations

- ^ Dewan 2008

- ^ Dewan 2009

- ^ Poovey 2001

- ^ Pourret, Olivier; Hursthouse, Andrew (2019). "It's Time to Replace the Term "Heavy Metals" with "Potentially Toxic Elements" When Reporting Environmental Research". Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 16 (22): 4446. doi:10.3390/ijerph16224446. PMC 6887782. PMID 31766104.

- ^ Zhang, Hongling; Walker, Tony R.; Davis, Emily; Ma, Guofeng (September 2019). "Ecological risk assessment of metals in small craft harbour sediments in Nova Scotia, Canada". Marine Pollution Bulletin. 146: 466–475. doi:10.1016/j.marpolbul.2019.06.068. PMID 31426182.

- ^ Srivastava & Goyal 2010, p. 2

- ^ Brathwaite & Rabone 1985, p. 363

- ^ Pourret, Olivier (August 2018). "On the Necessity of Banning the Term "Heavy Metal" from the Scientific Literature". Sustainability. 10 (8): 2879. doi:10.3390/su10082879.

- ^ Wright 2002, p. 288

- ^ Qureshi, Shabnam; Richards, Brian K.; McBride, Murray B.; Baveye, Philippe; Steenhuis, Tammo S. (2003). "Temperature and Microbial Activity Effects on Trace Element Leaching from Metalliferous Peats". Journal of Environmental Quality. 32 (6): 2067–75. doi:10.2134/jeq2003.2067. PMID 14674528.

- ^ Harvey, Handley & Taylor 2015

- ^ Howell et al. 2012; Cole et al. 2011, pp. 2589‒2590

- ^ Finch, Hillyer & Leopold 2015, pp. 849–850

- ^ Aggrawal 2014, p. 680

- ^ Di Maio 2001, p. 527

- ^ Lovei 1998, p. 15

- ^ Perry & Vanderklein 1996, p. 336

- ^ Houlton 2014, p. 50

- ^ Balasubramanian, He & Wang 2009, p. 476

- ^ Worsztynowicz & Mill 1995, p. 361

- ^ Camobreco, Vincent J.; Richards, Brian K.; Steenhuis, Tammo S.; Peverly, John H.; McBride, Murray B. (November 1996). "Movement of heavy metals through undisturbed and homogenized soil columns". Soil Science. 161 (11): 740–750. Bibcode:1996SoilS.161..740C. doi:10.1097/00010694-199611000-00003.

- ^ Radojevic & Bashkin 1999, p. 406

- ^ Guney, Mert; Zagury, Gerald J. (4 January 2014). "Bioaccessibility of As, Cd, Cu, Ni, Pb, and Sb in Toys and Low-Cost Jewelry". Environmental Science & Technology. 48 (2): 1238–1246. Bibcode:2014EnST...48.1238G. doi:10.1021/es4036122. PMID 24345102.

- ^ Qu et al. 2014, p. 144

- ^ Pezzarossa, Gorini & Petruzelli 2011, p. 94

- ^ Lanids, Sofield & Yu 2000, p. 269

- ^ Neilen & Marvin 2008, p. 10

- ^ Afal & Wiener 2014

- ^ Wanklyn & Chapman 1868, pp. 73–8; Cameron 1871, p. 484

- ^ Blake 1884

- ^ Dueck 2000, pp. 1–3, 46, 53

- ^ Dyer 2009

- ^ Whorton 2011, p. 356

- ^ Notman 2014

- ^ Zhao, Zhu & Sui 2006

- ^ Waldron 1983

- ^ Emsely 2011, p. 326

- ^ Davidson, Myers & Weiss 2004, p. 1025

- ^ New Scientist August 2014, p. 4

- ^ Pearce 2007; Needleman 2004

- ^ Rogers 2000, p. 41

- ^ Gilbert & Weiss 2006

- ^ Prioreschi 1998, p. 279

- ^ Hillman et al. 2015, pp. 3353–3354

- ^ Hillman et al. 2015, p. 3349

- ^ World Health Organization 2013

- ^ Torrice 2016

- ^ Harvey, Handley & Taylor 2015

- ^ Barceloux & Barceloux 1999

- ^ Newman 1890

- ^ Haines & Nieboer 1988, p. 504

- ^ National Research Council 1974, p. 68

- ^ Tovey 2011; Jones 2011; O'Brien & Aston

- ^ Vallero & Letcher 2013, p. 240

- ^ Vallero & Letcher 2013, pp. 239–241

- ^ Pritchard 2010

- ^ Mulvihill & Pritchard 2010

- ^ Cs uros 1997, p. 124

- ^ Blann & Ahmed 2014, p. 465

- ^ American Cancer Society 2008; National Capital Poison Center 2010

- ^ Evanko & Dzombak 1997, pp. 1, 14–40

- ^ Bánfalvi 2011, p. 12

- ^ Chowdhury 1987