Testicular Cancer

Overview

Testicular cancer is a growth of cells that starts in the testicles. The testicles, which are also called testes, are in the scrotum. The scrotum is a loose bag of skin underneath the penis. The testicles make sperm and the hormone testosterone.

Testicular cancer isn't a common type of cancer. It can happen at any age, but it happens most often between the ages of 15 and 45.

The first sign of testicular cancer often is a bump or lump on a testicle. The cancer cells can grow quickly. They often spread outside the testicle to other parts of the body.

Testicular cancer is highly treatable, even when it spreads to other parts of the body. Treatments depend on the type of testicular cancer that you have and how far it has spread. Common treatments include surgery and chemotherapy.

Symptoms

Signs and symptoms of testicular cancer include:

- A lump or swelling in either testicle

- A feeling of heaviness in the scrotum

- A dull ache in the lower belly or groin

- Sudden swelling in the scrotum

- Pain or discomfort in a testicle or the scrotum

- Enlargement or tenderness of the breast tissue

- Back pain

Usually testicular cancer only happens in one testicle.

When to see a doctor

See your health care provider if you detect any symptoms that last longer than two weeks. These include pain, swelling or lumps in your testicles or groin area.

Causes

It's not clear what causes most testicular cancers.

Testicular cancer starts when something causes changes to the DNA of testicle cells. A cell's DNA holds the instructions that tell the cell what to do. The changes tell the cells to grow and multiply quickly. The cancer cells go on living when healthy cells would die as part of their natural life cycle. This causes a lot of extra cells in the testicle that can form a mass called a tumor.

In time, the tumor can grow beyond the testicle. Some cells might break away and spread to other parts of the body. Testicular cancer most often spreads to the lymph nodes, liver and lungs. When testicular cancer spreads, it's called metastatic testicular cancer.

Nearly all testicular cancers begin in the germ cells. The germ cells in the testicle make sperm. It's not clear what causes DNA changes in the germ cells.

Risk factors

Factors that may increase your risk of testicular cancer include:

- Having an undescended testicle, which is called cryptorchidism. The testes form in the belly during fetal development. They typically descend into the scrotum before birth. If you have a testicle that never descended, your risk of testicular cancer is higher. The risk is increased even if you've had surgery to move the testicle to the scrotum.

- Having a family history of testicular cancer. If testicular cancer runs in your family, you might have an increased risk.

- Being a young adult. Testicular cancer can happen at any age. But it's most common in teens and young adults between 15 and 45.

- Being white. Testicular cancer is most common in white people.

Prevention

There's no way to prevent testicular cancer. If you get testicular cancer, there's nothing you could have done to prevent it.

Testicular cancer screening

Some health care providers recommend regular testicle self-exams. During a testicular self-exam you feel your testicles for any lumps or other changes.

Not all health care providers agree with this recommendation. There's no research to show that self-exams can lower the risk of dying of testicular cancer. Even when it is found at a late stage, testicular cancer is likely to be cured.

Still, you might find it helpful to become aware of the usual feel of your testicles. You can do this by doing a testicular self-exam. If you notice any changes that last longer than two weeks, make an appointment with your health care provider.

Diagnosis

You might find lumps, swelling or other symptoms of testicular cancer on your own. They can be detected during an exam by a health care provider too. You'll need other tests to see if testicular cancer is causing your symptoms.

Tests used to diagnose testicular cancer include:

-

Ultrasound. A testicular ultrasound test uses sound waves to make pictures. It can be used to make pictures of the scrotum and testicles. During an ultrasound you lie on your back with your legs spread. A health care provider puts a clear gel on the scrotum. A hand-held probe is moved over the scrotum to make the pictures.

Ultrasound gives your provider more clues about any lumps around the testicle. It can help your provider see whether the lumps look like something that isn't cancer or if they look like cancer. An ultrasound shows whether the lumps are inside or outside the testicle. Lumps inside the testicle are more likely to be testicular cancer.

- Blood tests. A blood test can detect proteins made by testicular cancer cells. This type of test is called a tumor marker test. Tumor markers for testicular cancer include beta-human chorionic gonadotropin, alpha-fetoprotein and lactate dehydrogenase. Having these substances in your blood doesn't mean you have cancer. Having levels higher than is typical is a clue your health care team uses to understand what's going on in your body.

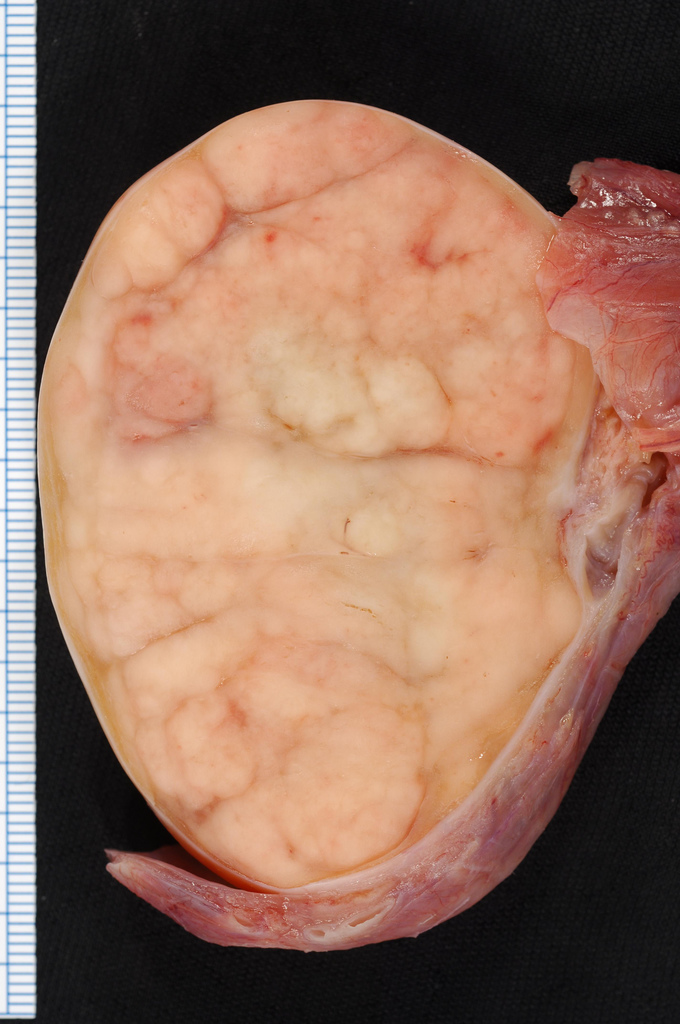

- Surgery to remove a testicle. If your health care provider thinks a lump on your testicle may be cancerous, you might have surgery to remove the testicle. The testicle is sent to a lab for testing. The tests can show whether it's cancerous.

Determining the type of cancer

Tests on your cancer cells give your health care team information about the type of testicular cancer that you have. Your care team considers your cancer type when deciding on your treatment.

The most common types of testicular cancer include:

- Seminoma. Seminoma testicular cancers tend to happen at an older age. Seminomas often grow and spread more slowly than nonseminomas.

- Nonseminoma. Nonseminoma testicular cancers tend to happen earlier in life. They grow and spread quickly. Several types of nonseminomas exist. They include choriocarcinoma, embryonal carcinoma, teratoma and yolk sac tumor.

Other types of testicular cancer exist, but they are very rare.

Staging the cancer

Once your doctor confirms your diagnosis, the next step is to see whether the cancer has spread beyond the testicle. This is called the cancer's stage. It helps your health care team understand your prognosis and how likely your cancer is to be cured.

Tests for staging testicular cancer include:

- Computerized tomography (CT) scan. CT scans take a series of X-ray pictures of your belly, chest and pelvis. A health care provider checks the pictures for signs that cancer has spread.

- Blood tests. Tumor marker tests are often repeated after surgery to remove the testicle. The results help your health care provider decide whether you might need additional treatments to kill the cancer cells. Tumor marker tests might be used during and after cancer treatment to monitor your condition.

The stages of testicular cancer range from 0 to 3. In general, stage 0 and stage 1 cancers only affect the testicle and the area around it. At these early stages, the cancer hasn't spread to the lymph nodes or other parts of the body. Stage 2 testicular cancers have spread to the lymph nodes. When testicular cancer spreads to other parts of the body, it is stage 3. Not all stage 3 cancers have spread though. Stage 3 can also mean that the cancer is in the lymph nodes and the tumor marker results are very high.

Treatment

Testicular cancer treatment often involves surgery and chemotherapy. Which treatment options are best for you depends on the type of testicular cancer you have and its stage. Your health care team also considers your overall health and your preferences.

Surgery

Operations used to treat testicular cancer include:

- Surgery to remove the testicle. This procedure is called a radical inguinal orchiectomy. It's the first treatment for most testicular cancers. To remove the testicle, a surgeon makes a cut in the groin. The entire testicle is pulled out through the opening. A prosthetic, gel-filled testicle can be inserted if you choose. This might be the only treatment needed if the cancer hasn't spread beyond the testicle.

- Surgery to remove nearby lymph nodes. If there's concern that your cancer may have spread beyond your testicle, you might have surgery to remove some lymph nodes. To remove the lymph nodes, the surgeon makes a cut in the belly. The lymph nodes are tested in a lab to look for cancer. Surgery to remove lymph nodes is often used to treat the nonseminoma type of testicular cancer.

Testicular cancer surgery carries a risk of bleeding and infection. If you have surgery to remove lymph nodes, there's also a risk that a nerve might be cut. Surgeons take great care to protect the nerves. Sometimes cutting a nerve can't be avoided. This can lead to problems with ejaculating, but it generally doesn't affect your ability to get an erection. Ask your health care provider about options for preserving your sperm before surgery.

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy treatment uses strong medicines to kill cancer cells. Chemotherapy travels throughout the body. It can kill cancer cells that may have spread beyond the testicle.

Chemotherapy is often used after surgery. It can help kill any cancer cells that are still in the body. When testicular cancer is very advanced, sometimes chemotherapy is used before surgery.

Side effects of chemotherapy depend on the specific medicines being used. Common side effects include fatigue, hearing loss and an increased risk of infection.

Chemotherapy also may cause your body to stop making sperm. Often, sperm production starts again as you get better after cancer treatment. But sometimes losing sperm production is permanent. Ask your health care provider about your options for preserving your sperm before chemotherapy.

Radiation therapy

Radiation therapy uses high-powered energy beams to kill cancer cells. The radiation can come from X-rays, protons and other sources. During radiation therapy, you're positioned on a table and a large machine moves around you. The machine points the energy beams at precise points on your body.

Radiation therapy is sometimes used to treat the seminoma type of testicular cancer. Radiation therapy may be recommended after surgery to remove your testicle.

Radiation therapy typically isn't used to treat the nonseminoma type of testicular cancer.

Side effects may include nausea and fatigue. Radiation therapy also can temporarily lower sperm counts. This can affect your fertility. Ask your health care provider about your options for preserving your sperm before radiation therapy.

Immunotherapy

Immunotherapy is treatment with medicine that helps your body's immune system kill cancer cells. Your immune system fights off diseases by attacking germs and other cells that shouldn't be in your body. Cancer cells survive by hiding from the immune system. Immunotherapy helps the immune system cells find and kill the cancer cells.

Immunotherapy is sometimes used for advanced testicular cancer. It might be an option if the cancer doesn't respond to other treatments.

Clinical trials

Explore Mayo Clinic studies testing new treatments, interventions and tests as a means to prevent, detect, treat or manage this condition.

Coping and support

Each person comes to terms with a testicular cancer diagnosis in an individual way. You may feel scared and unsure of your future after your diagnosis. While feelings of anxiety may never go away, you can make a plan to help manage your emotions. Try to:

- Learn enough about testicular cancer to feel comfortable making decisions about your care. Write down questions and ask them at your next appointment. Ask your health care team for sources that can help you learn more about testicular cancer. Good places to start include the National Cancer Institute and the American Cancer Society.

- Take care of yourself. Make healthy choices in your everyday life to prepare for cancer treatment. Eat a healthy diet with a variety of fruits and vegetables. Get plenty of rest so that you wake each morning feeling refreshed. Find ways to reduce stress so that you can concentrate on getting well. Try to exercise most days of the week. If you smoke, stop. Talk to your doctor about medicines and other ways to help you stop smoking.

- Connect with other cancer survivors. Find other testicular cancer survivors in your community or online. Contact the American Cancer Society for support groups in your area.

- Stay connected with loved ones. Your family and friends are just as concerned for your health as you are. They want to help, so don't turn down their offers to assist. Close friends and family will listen when you need someone to talk to or provide a distraction when you're feeling down.

Preparing for your appointment

Make an appointment with your usual health care provider if you have any symptoms that worry you.

If your provider suspects you could have testicular cancer, you may be referred to a specialist. This might be a doctor who diagnoses and treats conditions of the urinary tract and male reproductive system. This doctor is called a urologist. Or you might see a doctor who specializes in treating cancer. This doctor is called an oncologist.

What you can do

Because appointments can be brief, it's a good idea to be prepared. Try to:

- Be aware of any pre-appointment restrictions. At the time you make the appointment, ask if there's anything you need to do in advance.

- Write down any symptoms you're experiencing, including any that may seem unrelated to the reason for which you scheduled the appointment.

- Write down key personal information, including any other medical conditions, major stresses or recent life changes.

- Make a list of all medications, vitamins or supplements you're taking.

- Consider taking a family member or friend along. Sometimes it's hard to take in all the information provided during an appointment. Someone who comes with you may remember something that you missed or forgot.

What to expect from your doctor

Your health care provider is likely to ask you many questions. Being ready to answer them may allow more time to cover other points you want to address. Your provider may ask:

- When did you begin experiencing symptoms?

- Have your symptoms been continuous or occasional?

- How severe are your symptoms?

- What, if anything, seems to improve your symptoms?

- What, if anything, seems to worsen your symptoms?

What you can do in the meantime

Your time with your provider is limited. Make a list of questions so you're ready to make the most of your time together. List your questions from most important to least important in case time runs out. For testicular cancer, some basic questions to ask include:

- Do I have testicular cancer?

- What type of testicular cancer do I have?

- Can you explain my pathology report to me? May I have a copy of my pathology report?

- What is the stage of my testicular cancer?

- Will I need any additional tests?

- What are my treatment options?

- What are the chances that treatment will cure my testicular cancer?

- What are the side effects and risks of each treatment option?

- Is there one treatment that you think is best for me?

- What would you recommend to a friend or family member in my situation?

- Should I see a specialist? What will that cost, and will my insurance cover it?

- If I would like a second opinion, can you recommend a specialist?

- I'm concerned about my ability to have children in the future. What can I do before treatment to plan for the possibility of infertility?

- Are there brochures or other printed material that I can take with me? What websites do you recommend?

In addition to the questions that you've prepared to ask your doctor, don't hesitate to ask questions you think of during your appointment.