Sex-Selective Abortion

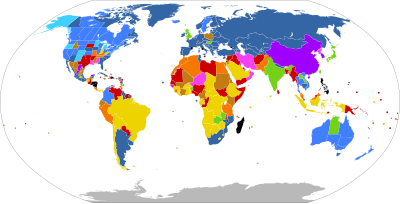

Sex-selective abortion is the practice of terminating a pregnancy based upon the predicted sex of the infant. The selective abortion of female fetuses is most common where male children are valued over female children, especially in parts of East Asia and South Asia (particularly in countries such as People's Republic of China, India and Pakistan), as well as in the Caucasus, Western Balkans, and to a lesser extent North America.

Sex selective abortion was first documented in 1975, and became commonplace by the late 1980s in South Korea and China and around the same time or slightly later in India.

Sex-selective abortion affects the human sex ratio—the relative number of males to females in a given age group, with China and India, the two most populous countries of the world, having unbalanced gender ratios. Studies and reports focusing on sex-selective abortion are predominantly statistical; they assume that birth sex ratio—the overall ratio of boys and girls at birth—for a regional population is an indicator of sex-selective abortion. This assumption has been questioned by some scholars.

According to demographic scholarship, the expected birth sex ratio range is 103 to 107 males to 100 females at birth.

Human sex ratio at birth

Sex-selective abortion affects the human sex ratio—the relative number of males to females in a given age group. Studies and reports that discuss sex-selective abortion are based on the assumption that birth sex ratio—the overall ratio of boys and girls at birth for a regional population, is an indicator of sex-selective abortion.

The natural human sex ratio at birth was estimated, in a 2002 study, to be close to 106 boys to 100 girls. Human sex ratio at birth that is significantly different from 106 is often assumed to be correlated to the prevalence and scale of sex-selective abortion. Countries considered to have significant practices of sex-selective abortion are those with birth sex ratios of 108 and above (selective abortion of females), and 102 and below (selective abortion of males). This assumption is controversial, and the subject of continuing scientific studies.

High or low human sex ratio implies sex-selective abortion

One school of scholars suggest that any birth sex ratio of boys to girls that is outside of the normal 105–107 range, necessarily implies sex-selective abortion. These scholars claim that both the sex ratio at birth and the population sex ratio are remarkably constant in human populations. Significant deviations in birth sex ratios from the normal range can only be explained by manipulation, that is sex-selective abortion.

In a widely cited article, Amartya Sen compared the birth sex ratio in Europe (106) and United States (105) with those in Asia (107+) and argued that the high sex ratios in East Asia, West Asia and South Asia may be due to excessive female mortality. Sen pointed to research that had shown that if men and women receive similar nutritional and medical attention and good health care then females have better survival rates, and it is the male which is the genetically fragile sex.

Sen estimated 'missing women' from extra women who would have survived in Asia if it had the same ratio of women to men as Europe and United States. According to Sen, the high birth sex ratio over decades, implies a female shortfall of 11% in Asia, or over 100 million women as missing from the 3 billion combined population of South Asia, West Asia, North Africa and China.

High or low human sex ratio may be natural

Other scholars question whether birth sex ratio outside 103–107 can be due to natural reasons. William James and others suggest that conventional assumptions have been:

- there are equal numbers of X and Y chromosomes in mammalian sperms

- X and Y stand equal chance of achieving conception

- therefore equal number of male and female zygotes are formed, and that

- therefore any variation of sex ratio at birth is due to sex selection between conception and birth.

James cautions that available scientific evidence stands against the above assumptions and conclusions. He reports that there is an excess of males at birth in almost all human populations, and the natural sex ratio at birth is usually between 102 and 108. However the ratio may deviate significantly from this range for natural reasons such as early marriage and fertility, teenage mothers, average maternal age at birth, paternal age, age gap between father and mother, late births, ethnicity, social and economic stress, warfare, environmental and hormonal effects. This school of scholars support their alternate hypothesis with historical data when modern sex-selection technologies were unavailable, as well as birth sex ratio in sub-regions, and various ethnic groups of developed economies. They suggest that direct abortion data should be collected and studied, instead of drawing conclusions indirectly from human sex ratio at birth.

James' hypothesis is supported by historical birth sex ratio data before technologies for ultrasonographic sex-screening were discovered and commercialized in the 1960s and 1970s, as well by reverse abnormal sex ratios currently observed in Africa. Michel Garenne reports that many African nations have, over decades, witnessed birth sex ratios below 100, that is more girls are born than boys. Angola, Botswana and Namibia have reported birth sex ratios between 94 and 99, which is quite different than the presumed 104 to 106 as natural human birth sex ratio.

John Graunt noted that in London over a 35-year period in the 17th century (1628–62), the birth sex ratio was 1.07; while Korea's historical records suggest a birth sex ratio of 1.13, based on 5 million births, in 1920s over a 10-year period. Other historical records from Asia too support James' hypothesis. For example, Jiang et al. claim that the birth sex ratio in China was 116–121 over a 100-year period in the late 18th and early 19th centuries; in the 120–123 range in the early 20th century; falling to 112 in the 1930s.

Data on human sex ratio at birth

In the United States, the sex ratios at birth over the period 1970–2002 were 105 for the white non-Hispanic population, 104 for Mexican Americans, 103 for African Americans and Native Americans, and 107 for mothers of Chinese or Filipino ethnicity. Among Western European countries c. 2001, the ratios ranged from 104 to 107. In the aggregated results of 56 Demographic and Health Surveys in African countries, the birth sex ratio was found to be 103, though there is also considerable country-to-country, and year-to-year variation.

In a 2005 study, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services reported sex ratio at birth in the United States from 1940 over 62 years. This statistical evidence suggested the following: For mothers having their first baby, the total sex ratio at birth was 106 overall, with some years at 107. For mothers having babies after the first, this ratio consistently decreased with each additional baby from 106 towards 103. The age of the mother affected the ratio: the overall ratio was 105 for mothers aged 25 to 35 at the time of birth; while mothers who were below the age of 15 or above 40 had babies with a sex ratio ranging between 94 and 111, and a total sex ratio of 104. This United States study also noted that American mothers of Hawaiian, Filipino, Chinese, Cuban and Japanese ethnicity had the highest sex ratio, with years as high as 114 and average sex ratio of 107 over the 62-year study period. Outside of United States, European nations with extensive birth records, such as Finland, report similar variations in birth sex ratios over a 250-year period, that is from 1751 to 1997 AD.

In 2017, according to CIA estimates, the countries with the highest birth sex ratio were Liechtenstein (125), Northern Mariana Islands (116), China (114), Armenia (112), Falkland Islands (112), India (112), Grenada (110), Hong Kong (110), Vietnam (110), Albania (109), Azerbaijan (109), San Marino (109), Isle of Man (108), Kosovo (108) and Macedonia (108). Also in 2017 the lowest ratio (i.e. more girls born) was in Nauru at (0.83). There were ratios of 102 and below in several countries, most of them African countries or Black/African majority population Caribbean countries: Angola, Aruba, Barbados, Bermuda, Burkina Faso, Burundi, Cabo Verde, Cameroon, Cayman Islands, Central African Republic, Chad, Comoros, Republic of the Congo, Côte d'Ivoire, Djibouti, Eritrea, Eswatini, Ethiopia, Gabon, The Gambia, Ghana, Guinea-Bissau, Haiti, Kazakhstan, Leshoto, Liberia, Madagascar, Malawi, Mali, Mauritania, Mozambique, Niger, Puerto Rico, Qatar, Senegal, Sierra Leone, Somalia, South Africa, Togo, Uganda, Zambia.

There is controversy about the notion of the exact natural sex ratio at birth. In a study around 2002, the natural sex ratio at birth was estimated to be close to 1.06 males/female. There is controversy whether sex ratios outside the 103-107 range are due to sex-selection, as suggested by some scholars, or due to natural causes. The claims that unbalanced sex ratios are necessary due to sex selection have been questioned by some researchers. Some researchers argue that an unbalanced sex ratio should not be automatically held as evidence of prenatal sex-selection; Michel Garenne reports that many African nations have, over decades, witnessed birth sex ratios below 100, that is more girls are born than boys. Angola, Botswana and Namibia have reported birth sex ratios between 94 and 99, which is quite different than the presumed "normal" sex ratio, meaning that significantly more girls have been born in such societies.

In addition, in many developing countries there are problems with birth registration and data collection, which can complicate the issue. With regard to the prevalence of sex selection, the media and international attention has focused mainly on a few countries, such as China, India and the Caucasus, ignoring other countries with a significant sex imbalance at birth. For example, Liechtenstein's sex ratio is far worse than that of those countries, but little has been discussed about it, and virtually no suggestions have been made that it may practice sex selection, although it is a very conservative country where women could not vote until 1984. At the same time, there have been accusations that the situation in some countries, such as Georgia, has been exaggerated. In 2017, Georgia' sex ratio at birth was 107, according to CIA statistics.

Data reliability

The estimates for birth sex ratios, and thus derived sex-selective abortion, are a subject of dispute as well. For example, United States' CIA projects the birth sex ratio for Switzerland to be 106, while the Switzerland's Federal Statistical Office that tracks actual live births of boys and girls every year, reports the latest birth sex ratio for Switzerland as 107. Other variations are more significant; for example, CIA projects the birth sex ratio for Pakistan to be 105, United Nations FPA office claims the birth sex ratio for Pakistan to be 110, while the government of Pakistan claims its average birth sex ratio is 111.

The two most studied nations with high sex ratio and sex-selective abortion are China and India. The CIA estimates a birth sex ratio of 112 for both in recent years. However, The World Bank claims the birth sex ratio for China in 2009 was 120 boys for every 100 girls; while United Nations FPA estimates China's 2011 birth sex ratio to be 118.

For India, the United Nations FPA claims a birth sex ratio of 111 over 2008–10 period, while The World Bank and India's official 2011 Census reports a birth sex ratio of 108. These variations and data reliability is important as a rise from 108 to 109 for India, or 117 to 118 for China, each with large populations, represent a possible sex-selective abortion of about 100,000 girls.

Prenatal sex discernment

The earliest post-implantation test, cell free fetal DNA testing, involves taking a blood sample from the mother and isolating the small amount of fetal DNA that can be found within it. When performed after week seven of pregnancy, this method is about 98% accurate.

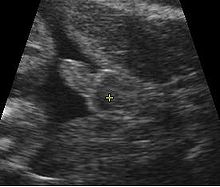

Obstetric ultrasonography, either transvaginally or transabdominally, checks for various markers of fetal sex. It can be performed at or after week 12 of pregnancy. At this point, 3⁄4 of fetal sexes can be correctly determined, according to a 2001 study. Accuracy for males is approximately 50% and for females almost 100%. When performed after week 13 of pregnancy, ultrasonography gives an accurate result in almost 100% of cases.

The most invasive measures are chorionic villus sampling (CVS) and amniocentesis, which involve testing of the chorionic villus (found in the placenta) and amniotic fluid, respectively. Both techniques typically test for chromosomal disorders but can also reveal the sex of the child and are performed early in the pregnancy. However, they are often more expensive and more dangerous than blood sampling or ultrasonography, so they are seen less frequently than other sex determination techniques.

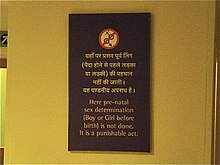

Prenatal sex determination is restricted in many countries, and so is the communication of the sex of the fetus to the pregnant woman or her family, in order to prevent sex selective abortion. In India, prenatal sex determination is regulated under the Pre-conception and Prenatal Diagnostic Techniques (Prohibition of Sex Selection) Act 1994.

- Availability

China launched its first ultrasonography machine in 1979. Chinese health care clinics began introducing ultrasound technologies that could be used to determine prenatal sex in 1982. By 1991, Chinese companies were producing 5,000 ultrasonography machines per year. Almost every rural and urban hospital and family planning clinics in China had a good quality sex discernment equipment by 2001.

The launch of ultrasonography technology in India too occurred in 1979, but its expansion was slower than China. Ultrasound sex discernment technologies were first introduced in major cities of India in the 1980s, its use expanded in India's urban regions in the 1990s, and became widespread in the 2000s.

Prevalence

The exact prevalence of sex-selective abortion is uncertain, with the practice taking place in some societies as an open secret, without formal data on its frequency. Some authors argue that it is quite difficult to explain why this practice takes place in some cultures and not others, and that sex-selective abortion cannot be explained merely by patriarchal social norms, because most societies are male dominated, but only a minority practice sex-selective abortion.

Africa and the Middle East

Sex selective abortion based on son preference is significant in North Africa and the Middle East. Son preference is also a common justification for sex-selective abortion in some sub-Saharan African countries such as Nigeria.

Asia

The vast majority of sex-selective abortions take place in China and India, with 11.9 million and 10.6 million out of 23 million world-wide, according to a 2019 study.

China

China, the most populous country in the world, has a serious problem with an unbalanced sex ratio population. A 2010 BBC article stated that the sex birth ratio was 119 boys born per 100 girls, which rose to 130 boys per 100 girls in some rural areas. The Chinese Academy of Social Sciences estimated that more than 24 million Chinese men of marrying age could find themselves without spouses by 2020. In 1979, China enacted the one child policy, which, within the country's deeply patriarchal culture, resulted in an unbalanced birth sex ratio. The one child policy was enforced throughout the years, including through forced abortions and forced sterilizations, but gradually loosened until it was formally abolished in 2015.

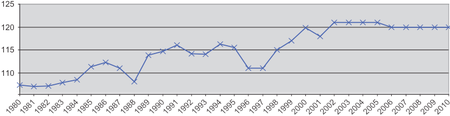

When sex ratio began being studied in China in 1960, it was still within the normal range. However, it climbed to 111.9 by 1990 and to 118 by 2010 per its official census. Researchers believe that the causes of this sex ratio imbalance are increased female infant mortality, underreporting of female births and sex-selective abortion. According to Zeng et al. (1993), the most prominent cause is probably sex-selective abortion, but this is difficult to prove that in a country with little reliable birth data because of the hiding of "illegal" (under the One-Child Policy) births.

These illegal births have led to underreporting of female infants. Zeng et al., using a reverse survival method, estimate that underreporting keeps about 2.26% male births and 5.94% female births off the books. Adjusting for unreported illegal births, they conclude that the corrected Chinese sex ratio at birth for 1989 was 111 rather than 115. These national averages over time, mask the regional sex ratio data. For example, in 2005 Anhui, Jiangxi, Shaanxi, Hunan and Guangdong, had a sex ratio at birth of more than 130.

Traditional Chinese techniques have been used to determine sex for hundreds of years, primarily with unknown accuracy. It was not until ultrasonography became widely available in urban and rural China that sex was able to be determined scientifically. In 1986, the Ministry of Health posted the Notice on Forbidding Prenatal Sex Determination, but it was not widely followed. Three years later, the Ministry of Health outlawed the use of sex determination techniques, except for in diagnosing hereditary diseases. However, many people have personal connections to medical practitioners and strong son preference still dominates culture, leading to the widespread use of sex determination techniques.

Hardy, Gu, and Xie suggest sex-selective abortion is more prevalent in rural China because son preference is much stronger there. Urban areas of China, on average, are moving toward greater equality for both sexes, while rural China tends to follow more traditional views of gender. This is partially due to the belief that, while sons are always part of the family, daughters are only temporary, going to a new family when they marry. Additionally, if a woman's firstborn child is a son, her position in society moves up, while the same is not true of a firstborn daughter. Families in China are aware of the critical lack of female children and its implication on marriage prospects in the future; many parents are beginning to work extra when their sons are young so that they will be able to pay for a bride for them.

In a 2005 study, Zhu, Lu, and Hesketh found that the highest sex ratio was for those ages 1–4, and two provinces, Tibet and Xinjiang, had sex ratios within normal limits. Two other provinces had a ratio over 140, four had ratios between 130–139, and seven had ratios between 120–129, each of which is significantly higher than the natural sex ratio.

The birth sex ratio in China, according to a 2012 news report, has decreased to 117 males born for every 100 females. The sex ratio peaked in 2004 at around 121, and had declined to around 112 in 2017. The ratio was forecast to drop below 112 by 2020 and 107 by 2030, according to the National Population Development Outline by the State Council.

India

India's 2001 census revealed a national 0–6 age child sex ratio of 108, which increased to 109 according to 2011 census (927 girls per 1000 boys and 919 girls per 1000 boys respectively, compared to expected normal ratio of 943 girls per 1000 boys). The national average masks the variations in regional numbers according to 2011 census—Haryana's ratio was 120, Punjab's ratio was 118, Jammu & Kashmir was 116, and Gujarat's ratio was 111. The 2011 Census found eastern states of India had birth sex ratios between 103 and 104, lower than normal. In contrast to decadal nationwide census data, small non-random sample surveys report higher child sex ratios in India.

The child sex ratio in India shows a regional pattern. India's 2011 census found that all eastern and southern states of India had a child sex ratio between 103 and 107, typically considered as the “natural ratio.” The highest sex ratios were observed in India's northern and northwestern states – Haryana (120), Punjab (118) and Jammu & Kashmir (116). The western states of Maharashtra and Rajasthan 2011 census found a child sex ratio of 113, Gujarat at 112 and Uttar Pradesh at 111.

The Indian census data suggests there is a positive correlation between abnormal sex ratio and better socio-economic status and literacy. Urban India has higher child sex ratio than rural India according to 1991, 2001 and 2011 Census data, implying higher prevalence of sex selective abortion in urban India. Similarly, child sex ratio greater than 115 boys per 100 girls is found in regions where the predominant majority is Hindu, Muslim, Sikh or Christian; furthermore "normal" child sex ratio of 104 to 106 boys per 100 girls are also found in regions where the predominant majority is Hindu, Muslim, Sikh or Christian. These data contradict any hypotheses that may suggest that sex selection is an archaic practice which takes place among uneducated, poor sections or particular religion of the Indian society.

Rutherford and Roy, in their 2003 paper, suggest that techniques for determining sex prenatally that were pioneered in the 1970s, gained popularity in India. These techniques, claim Rutherford and Roy, became broadly available in 17 of 29 Indian states by the early 2000s. Such prenatal sex determination techniques, claim Sudha and Rajan in a 1999 report, where available, favored male births.

Arnold, Kishor, and Roy, in their 2002 paper, too hypothesize that modern fetal sex screening techniques have skewed child sex ratios in India. Ganatra et al., in their 2000 paper, use a small survey sample to estimate that 1⁄6 of reported abortions followed a sex determination test.

The Indian government and various advocacy groups have continued the debate and discussion about ways to prevent sex selection. The immorality of prenatal sex selection has been questioned, with some arguments in favor of prenatal discrimination as more humane than postnatal discrimination by a family that does not want a female child. Others question whether the morality of sex selective abortion is any different over morality of abortion when there is no risk to the mother nor to the fetus, and abortion is used as a means to end an unwanted pregnancy.

India passed its first abortion-related law, the so-called Medical Termination of Pregnancy Act of 1971, making abortion legal in most states, but specified legally acceptable reasons for abortion such as medical risk to mother and rape. The law also established physicians who can legally provide the procedure and the facilities where abortions can be performed, but did not anticipate sex selective abortion based on technology advances.

With increasing availability of sex screening technologies in India through the 1980s in urban India, and claims of its misuse, the Government of India passed the Pre-natal Diagnostic Techniques Act (PNDT) in 1994. This law was further amended into the Pre-Conception and Pre-natal Diagnostic Techniques (Regulation and Prevention of Misuse) (PCPNDT) Act in 2004 to deter and punish prenatal sex screening and sex selective abortion. The impact of the law and its enforcement is unclear. United Nations Population Fund and India's National Human Rights Commission, in 2009, asked the Government of India to assess the impact of the law. The Public Health Foundation of India, an activist NGO in its 2010 report, claimed a lack of awareness about the Act in parts of India, inactive role of the Appropriate Authorities, ambiguity among some clinics that offer prenatal care services, and the role of a few medical practitioners in disregarding the law.

The Ministry of Health and Family Welfare of India has targeted education and media advertisements to reach clinics and medical professionals to increase awareness. The Indian Medical Association has undertaken efforts to prevent prenatal sex selection by giving its members Beti Bachao (save the daughter) badges during its meetings and conferences.

In November 2007, MacPherson estimated that 100,000 abortions every year continue to be performed in India solely because the fetus is female.

Pakistan

For Pakistan, the United Nations Population Fund, in its 2012 report estimates the Pakistan birth sex ratio to be 110. In the urban regions, particularly its densely populated region of Punjab, report a sex ratio above 112 (less than 900 females per 1000 males). Hudson and Den Boer estimate the resulting deficit to be about 6 million missing girls in Pakistan than what would normally be expected. Three different research studies, according to Klausen and Wink, note that Pakistan had the world's highest percentage of missing girls, relative to its total pre-adult female population.

In 2017, two Pakistani organisations discovered large cases of infanticide in Pakistani cities. This was lead by the Edhi Foundation and Chhipa Welfare Foundation. The infanticide was mainly almost all were female infants. The reason given by the local authorities were poverty and local customs, where boys are preferred to girls. However, the large discovery in Karachi shows that many of the female infants were killed because of the local Islamic clerics, who ordered out of wedlock babies should be disregarded. As, babies born out of wedlock in Islam is considered a sin.

From January 2017 to April 2018, Edhi Center foundation and Chhipa Welfare organisation have found 345 such new born babies dumped in garbage in Karachi only and 99 percent of them were girls.

“We have been dealing with such cases for years and there are a few such incidents which shook our souls as much. It left us wondering whether our society is heading back to primitive age,” Anwar Kazmi, a senior manager in Edhi Foundation Karachi, told The News.

Edhi Foundation has found 355 such dead infants from the garbage dumps across the country in 2017; 99 percent of them were identified girls. And Karachi has topped in this notorious ranking with 180 cases in 2017. As many as 72 dead girls have been buried in the first four months of this year by Edhi Foundation alone in the metropolitan city. The given data is just tip of the iceberg as Edhi foundation maintains the data of those cities where it provides services.

South Korea

Further information: Sex-selective abortion in South Korea

Sex-selective abortion gained popularity in the mid-1980s to early 1990s in South Korea, where selective female abortions were commonplace as male children were preferred. Historically, much of Korea's values and traditions were based on Confucianism that dictated the patriarchal system, motivating the heavy preference for sons. Additionally, even though the abortion ban existed, the combination of son preference and availability of sex-selective technology led to an increasing number of sex-selective abortions and boys born. As a result, South Korea experienced drastically high sex ratios around mid-1980s to early 1980s. However, in recent years, with the changes in family policies and modernization, attitudes towards son preference have changed, normalizing the sex ratio and lowering the number of sex-selective abortions. With that being said, there has been no explicit data on the number of induced sex selective abortions reportedly performed due to the abortion ban and controversiality surrounding the topic. Therefore, scholars have been continuously analyzing and generating connections among sex-selection, abortion policies, gender discrimination, and other cultural factors.

Other Asian countries

Other countries with large populations but high sex ratios include Vietnam. The United Nations Population Fund, in its 2012 report, claims the birth sex ratio of Vietnam at 111 with its densely populated Red River Delta region at 116.

Taiwan has reported a sex ratio at birth between 1.07 and 1.11 every year, across 4 million births, over the 20-year period from 1991 to 2011, with the highest birth sex ratios in the 2000s. Sex-selective abortion is reported to be common in South Korea too, but its incidence has declined in recent years. As of 2015, South Korea's sex ratio at birth was 1.07 male/female. In 2015, Hong Kong had a sex ratio at birth of 1.12 male/female. A 2001 study on births in the late 1990s concluded that "sex selection or sex-selective abortion might be practiced among Hong Kong Chinese women".

Recently, a rise in the sex ratio at birth has been noted in some parts of Nepal, most notably in the Kathmandu Valley, but also in districts such as Kaski. High sex ratios at birth are most notable amongst richer, more educated sections of the population in urban areas.

Europe

Abnormal sex ratios at birth, possibly explained by growing incidence of sex-selective abortion, have also been noted in some other countries outside South and East Asia. According to CIA, the most imbalanced birth sex ratios in Europe (2017) are in Liechtenstein, Armenia, Albania, Azerbaijan, San Marino, Kosovo and Macedonia; with Liechtenstein having the most imbalanced sex ratio in the world.

Caucasus

The Caucasus has been named a "male-dominated region", and as families have become smaller in recent years, the pressures to have sons has increased. Before the dissolution of the Soviet Union in the early 1990s, the birth sex ratio in Caucasus countries such as Azerbaijan, Armenia and Georgia was in the 105 to 108 range. After the collapse, the birth sex ratios sharply climbed and have remained high for the last 20 years. Armenia, Georgia, and Azerbaijan have seen strongly imbalanced birth sex ratios in the first decade of the 21st century. In Georgia, the birth sex ratio for the years 2005–2009 was cited by The Economist to be about 120, a trend The Economist claims suggests that the practice of sex-selective abortion in the Caucasus has been similar to those in East Asia and South Asia in recent decades.

According to an article in The Economist the sex ratio in Armenia is seen to be a function of birth order. The article claimed that among first born children, there are 138 boys for every 100 girls. Overall, the birth sex ratio in Armenia exceeded 115 in some years, far higher than India's which was cited at 108. While these high birth sex ratios suggest sex-selective abortion, there is no direct evidence of observed large-scale sex-selective abortions in Caucasus.

According to latest CIA data, the 2017 sex ratio in the region is 112 for Armenia, 109 for Azerbaijan, and 107 for Georgia.

Southeast Europe

An imbalanced birth sex ratio has been present in the 21st century in the Western Balkans, in countries such as Albania, Macedonia, Kosovo and Montenegro. Scholars claim this suggests that sex-selective abortions are common in southeast Europe. As of 2017, according to CIA estimates, Albania's birth sex ratio is 109. According to Eurostat and birth record data over 2008–11, the birth sex ratios of Albania and Montenegro for that period were 112 and 110 respectively. In recent years, Montenegrin health authorities have expressed concern with regard to the significant imbalance between the number of male and female births. However the data from CIA in 2017 cites the birth ratio for Montenegro within the normal range, at 106. In recent years, the birth registration data for Macedonia and Kosovo indicate unbalanced birth sex ratios, including a birth rate in 2010 of 112 for Kosovo. As 2017, CIA cited both Macedonia and Kosovo at 108.

United States

Like in other countries, sex-selective abortion is difficult to track in the United States because of lack of data.

While some parents in United States do not practice sex-selective abortion, there is certainly a trend toward male preference. According to a 2011 Gallup poll, if they were only allowed to have one child, 40% of respondents said they would prefer a boy, while only 28% preferred a girl. When told about prenatal sex selection techniques such as sperm sorting and in vitro fertilization embryo selection, 40% of Americans surveyed thought that picking embryos by sex was an acceptable manifestation of reproductive rights. These selecting techniques are available at about half of American fertility clinics, as of 2006. However, other studies show a larger preference for females. According to the Parliamentary Office of Science and Technology, 80% of American couples who wanted to get gender selection wanted girls over boys.

However, it is notable that minority groups that immigrate into the United States bring their cultural views and mindsets into the country with them. A study carried out at a Massachusetts infertility clinic shows that the majority of couples using these techniques, such as Preimplantation genetic diagnosis came from a Chinese or Asian background. This is thought to branch from the social importance of giving birth to male children in China and other Asian countries.

A study of the 2000 United States Census suggests possible male bias in families of Chinese, Korean and Indian immigrants, which was getting increasingly stronger in families where the first one or two children were female. In those families where the first two children were girls, the birth sex ratio of the third child was 1.51:1.

Because of this movement toward sex preference and selection, many bans on sex-selective abortion have been proposed at the state and federal level. In 2010 and 2011, sex-selective abortions were banned in Oklahoma and Arizona, respectively. Legislators in Georgia, West Virginia, Michigan, Minnesota, New Jersey, and New York have also tried to pass acts banning the procedure.

Other countries

A 2013 study by John Bongaarts based on surveys in 61 major countries calculates the sex ratios that would result if parents had the number of sons and daughters they want. In 35 countries, claims Bongaarts, the desired birth sex ratio in respective countries would be more than 110 boys for every 100 girls if parents in these countries had a child matching their preferred gender (higher than India's, which The Economist claims is 108).

Estimates of missing women

Estimates of implied missing girls, considering the "normal" birth sex ratio to be the 103–107 range, vary considerably between researchers and underlying assumptions for expected post-birth mortality rates for men and women. For example, a 2005 study estimated that over 90 million females were "missing" from the expected population in Afghanistan, Bangladesh, China, India, Pakistan, South Korea and Taiwan alone, and suggested that sex-selective abortion plays a role in this deficit. For early 1990s, Sen estimated 107 million missing women, Coale estimated 60 million as missing, while Klasen estimated 89 million missing women in China, India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Nepal, West Asia and Egypt. Guilmoto, in his 2010 report, uses recent data (except for Pakistan), and estimates a much lower number of missing girls, but notes that the higher sex ratios in numerous countries have created a gender gap – shortage of girls – in the 0–19 age group.

| Country | Gender gap 0–19 age group (2010) |

% of minor females |

Region | Religious situation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Afghanistan | 265,000 | 3.0 | South Asia | Mostly Islam |

| Albania | 21,000 | 4.2 | Southeast Europe | Religiously diverse |

| Armenia | 35,000 | 8.4 | Caucasus | Mostly Christianity |

| Azerbaijan | 111,000 | 8.3 | Caucasus | Mostly Islam |

| Bangladesh | 416,000 | 1.4 | South Asia | Mostly Islam |

| China | 25,112,000 | 15.0 | East Asia | Religiously diverse |

| Georgia | 24,000 | 4.6 | Caucasus | Mostly Christianity |

| India | 12,618,000 | 5.3 | South Asia | Mostly Hinduism |

| Montenegro | 3,000 | 3.6 | Southeast Europe | Mostly Christianity |

| Nepal | 125,000 | 1.8 | South Asia | Mostly Hinduism |

| Pakistan | 206,000 | 0.5 | South Asia | Mostly Islam |

| South Korea | 336,000 | 6.2 | East Asia | Religiously diverse |

| Singapore | 21,000 | 3.5 | Southeast Asia | Religiously diverse |

| Vietnam | 139,000 | 1.0 | Southeast Asia | Religiously diverse |

Disparate gendered access to resources

Although there is significant evidence of the prevalence of sex-selective abortions in many nations (especially India and China), there is also evidence to suggest that some of the variation in global sex ratios is due to disparate access to resources. As MacPherson (2007) notes, there can be significant differences in gender violence and access to food, healthcare, immunizations between male and female children. This leads to high infant and childhood mortality among girls, which causes changes in sex ratio.

Disparate, gendered access to resources appears to be strongly linked to socioeconomic status. Specifically, poorer families are sometimes forced to ration food, with daughters typically receiving less priority than sons. However, Klasen's 2001 study revealed that this practice is less common in the poorest families, but rises dramatically in the slightly less poor families. Klasen and Wink's 2003 study suggests that this is "related to greater female economic independence and fewer cultural strictures among the poorest sections of the population". In other words, the poorest families are typically less bound by cultural expectations and norms, and women tend to have more freedom to become family breadwinners out of necessity.

Increased sex ratios can be caused by disparities in aspects of life other than vital resources. According to Sen (1990), differences in wages and job advancement also have a dramatic effect on sex ratios. This is why high sex ratios are sometimes seen in nations with little sex-selective abortion. Additionally, high female education rates are correlated with lower sex ratios (World Bank 2011).

Lopez and Ruzikah (1983) found that, when given the same resources, women tend to outlive men at all stages