Neurodegeneration With Brain Iron Accumulation 3

A number sign (#) is used with this entry because of evidence that this form of neurodegeneration with brain iron accumulation (NBIA), here designated 'NBIA3,' is caused by heterozygous mutation in the FTL gene (134790) on chromosome 19q13. See NOMENCLATURE section.

For a general phenotypic description and a discussion of genetic heterogeneity of NBIA, see NBIA1 (234200).

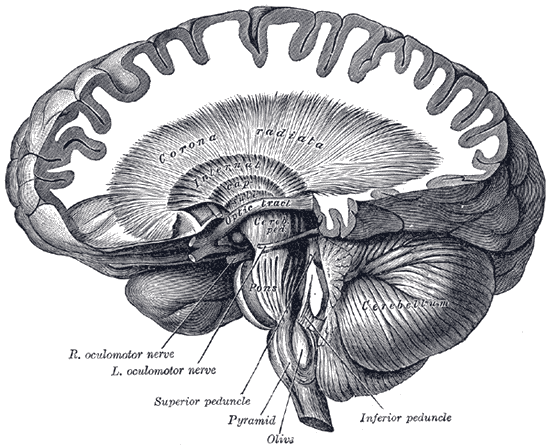

DescriptionNeurodegeneration with brain iron accumulation is a genetically heterogeneous disorder characterized by progressive iron accumulation in the basal ganglia and other regions of the brain, resulting in extrapyramidal movements, such as parkinsonism and dystonia. Age at onset, cognitive involvement, and mode of inheritance is variable (review by Gregory et al., 2009).

Clinical FeaturesCurtis et al. (2001) described a dominantly inherited late-onset basal ganglia disease variably presenting with extrapyramidal features similar to those of Huntington disease (143100) or parkinsonism. The disorder typically presented with involuntary movements at 40 to 55 years of age. Symptoms of extrapyramidal dysfunction included choreoathetosis, dystonia, spasticity, and rigidity, sometimes showing acute progression but not associated with significant cognitive decline or cerebellar involvement. MRI scan showed cavitation of the basal ganglia confirmed by brain pathology. Surviving affected family members lived within a 40-km radius of the home of the earliest founder that was traced (from records circa 1790), a member of a local family from the Cumbrian region of northern England. Patients had low serum ferritin levels and abnormal aggregates of ferritin and iron in the brain. Curtis et al. (2001) noted that iron deposition in the brain increases normally with age, especially in the basal ganglia, and is a suspected causative factor in several neurodegenerative diseases in which it correlates with visible pathology, possibly by its involvement in toxic free-radical reactions. Known neurologic disorders were excluded by routine diagnostic tests.

Chinnery et al. (2003) reported a French family in which 7 members developed dystonia between the ages of 24 and 58 years of age. Inheritance was autosomal dominant. Additional clinical features included dysarthria, chorea, parkinsonism, blepharospasm, and cerebellar signs. Two affected members had a frontal lobe syndrome, and 1 had dementia. MRI of 3 affected family members showed cystic changes in the basal ganglia. Skeletal muscle biopsy from 4 patients showed abnormalities of the mitochondrial respiratory chain. Devos et al. (2009) provided further information on 4 of the affected members from the French family reported by Chinnery et al. (2003). These patients developed symptoms between 24 and 44 years of age. Presenting features included dystonia, causing writing difficulties or a gait disorder, followed by rapid progression to orofacial, pharyngeal, and laryngeal dystonia. L-DOPA was not effective. None developed spasticity, abnormal reflexes, or marked tremor. Three deceased family members developed cerebellar ataxia. All developed a moderate subcortical/frontal dementia. Other atypical features included a limitation of vertical eye movements and mild dysautonomia, including orthostatic hypotension, constipation, and urinary incontinence. Brain imaging showed iron deposition and cystic cavitation of the basal ganglia. Serum ferritin levels were decreased.

Vidal et al. (2004) reported a large 5-generation French family in which 11 members had neuroferritinopathy inherited in an autosomal dominant pattern. Six affected family members were living at the time of the report. The proband first developed tremor at age 20 years. Thereafter, she had a progressive neurologic decline, characterized by frontal and subcortical cognitive impairment and involuntary movements in her mid-fifties, and pyramidal signs in her late fifties. She had dyskinesias, rigidity, hypertonicity, buccolingual dyskinesia, and dystonic posturing of the hands and feet. She became wheelchair-bound, was unable to feed herself, and died in a comatose state. Neuropathologic examination showed cerebellar and cerebral atrophy, cavitation of the putamen, and widespread ferritin inclusions in neurons and glia throughout the brain. Ferritin inclusions were also seen in extraneural tissue, including skin, muscle, and kidney. Serum ferritin was not measured. Vidal et al. (2004) noted the earlier age at onset in this family compared to the family reported by Curtis et al. (2001), as well as the prominent tremor and cognitive decline in the French family.

Maciel et al. (2005) reported a 19-year-old man with parkinsonism, ataxia, and corticospinal signs consistent with neuroferritinopathy. Genetic analysis detected a mutation in the FTL gene (A96T; 134790.0013) in the patient, his asymptomatic mother, and his asymptomatic 13-year-old brother. MRI showed bilateral pallidal necrosis in the patient and his mother, and all 3 mutation carriers had decreased serum ferritin. The patient also had mild nonprogressive cognitive deficit and episodic psychosis, which may have been unrelated since a noncarrying uncle had schizophrenia.

Chinnery et al. (2007) reported the clinical features of 41 individuals with neuroferritinopathy due to a 460insA mutation in the FTL gene (134790.0010). The mean age of onset was 39.4 years (range, 13-63), presenting with chorea in 50%, focal lower limb dystonia in 42.5%, and parkinsonism in 7.5%. Other variable features included writer's cramp, blepharospasm, and palatal tremor. The disease showed progression over 5 to 10 years, resulting in a generalized disorder with severe asymmetric motor disability and dystonia, dysphagia, and aphonia, although most remained ambulatory. None developed overt spasticity, ophthalmologic changes, or seizures. The majority of patients had normal psychometric profiles and no cognitive dysfunction except for defects in verbal fluency, even after 10 years. Two patients had evidence of a frontal/subcortical dementia after 10 years, but 1 had normal cognition 36 years after onset. Overall, however, many had subtle features of disinhibition and emotional lability. Five of 6 studied had mitochondrial chain respiratory defects in skeletal muscle biopsies. Laboratory studies showed low levels in most males and postmenopausal females, but normal levels in premenopausal females. Brain imaging showed iron deposition predominantly in the basal ganglia in all affected individuals and in 1 presymptomatic carrier. Some with advanced disease showed cystic degenerative changes. The majority of patients reported a family history of a movement disorder, which was often misdiagnosed as Huntington disease, and admission to a psychiatric institution. Treatment with iron depletion therapy did not provide any benefit, at least in the short term. Chinnery et al. (2007) concluded that isolated parkinsonism is unusual in neuroferritinopathy, and that cognitive changes are absent or subtle in the early stages. Devos et al. (2009) noted that 3 French patients reported by Chinnery et al. (2007) were found to carry a different mutation in the FTL gene (458dupA; 134790.0016).

Ohta et al. (2008) reported a Japanese mother and son with neuroferritinopathy confirmed by genetic analysis (134790.0015). The son developed hand tremors in his mid-teens and foot dragging at age 35. By age 42, he had generalized hypotonia, hyperextensibility, unsteady gait, aphonia, micrographia, hyperreflexia, and cognitive impairment. Rigidity, spasticity, dystonia, and chorea were not observed. His mother had hand tremors at age 10, difficulty walking at age 35, developed cognitive impairment and akinetic mutism, and died at age 64. Brain imaging in both patients showed symmetric cystic changes in the basal ganglia. The son had hyperintense lesions in the basal ganglia and substantia nigra on MRI. Ohta et al. (2008) suggested that the mutant FTL protein was unable to retain iron, which was released in the nervous system, causing oxidative damage.

Keogh et al. (2012) found that 3 asymptomatic descendants of known FTL mutation carriers who themselves were carriers of a mutation (460insA; 134790.0010) had evidence of iron deposition on brain imaging. In each case, the signal abnormalities were visible on T2*-weighted MRI. The abnormalities increased with age: 1 patient between 6 and 16 years had involvement of the substantia nigra, globus pallidus, and motor cortex; a patient between 17 and 25 years had additional involvement of the red nucleus and thalamus, but not the motor cortex; and the third patient, between 26 and 36 years, had additional involvement of the caudate. The findings indicated that iron deposition in neuroferritinopathy can begin decades before symptomatic presentation, and suggested that iron deposition initiates neurodegeneration.

MappingIn a family with adult-onset basal ganglia disease, Curtis et al. (2001) found linkage to a 3.5-cM region between D19S596 and D19S866 (maximum multipoint lod score of 6.38 for HRC.PCR3).

Molecular GeneticsIn an individual with adult-onset basal ganglia disease and in 5 apparently unrelated subjects with similar extrapyramidal symptoms, Curtis et al. (2001) identified an insertion mutation in the FTL gene (134790.0010). Curtis et al. (2001) proposed a dominant-negative or dominant gain-of-function effect rather than haploinsufficiency. An abnormality in ferritin strongly indicated a primary function for iron in the pathogenesis of this disease, for which they proposed the name 'neuroferritinopathy.'

In affected members of a French family with neuroferritinopathy reported by Chinnery et al. (2003), Devos et al. (2009) identified a mutation in the FTL gene (458dupA; 134790.0016). The family had originally been thought to have a different mutation (134790.0010) (Chinnery et al., 2003).

Vidal et al. (2004) identified a mutation in the FTL gene (498insTC; 134790.0014) in affected members of a French family with neuroferritinopathy.

In a healthy 52-year-old woman who was a control subject in a genetic study of hyperferritinemia-cataract syndrome, Cremonesi et al. (2004) identified a heterozygous mutation in the ATG start codon of the FTL gene (M1V; 134790.0018), predicted to disable protein translation and expression. She had no history of iron deficiency anemia or neurologic dysfunction. Hematologic examination was normal except for decreased serum L-ferritin (615604). The findings suggested that L-ferritin has no effect on systemic iron metabolism. The report also indicated that neuroferritinopathy is not a consequence of haploinsufficiency of L-ferritin, but likely results from gain-of-function mutations in the FTL gene.

Population GeneticsIn a nationwide survey of Japanese patients, Hirayama et al. (1994) estimated the prevalence of all forms of spinocerebellar degeneration to be 4.53 per 100,000. Of these, 1.5% were thought to have striatonigral degeneration, defined by the authors as a sporadic disorder with onset after middle age with mainly parkinsonian signs and occasionally accompanied by cerebellar ataxia, autonomic disturbance, and cerebellar atrophy on scanning.

NomenclatureAlthough some (see, e.g., Chinnery et al., 2007) have referred to neuroferritinopathy due to FTL mutations as 'neurodegeneration with brain iron accumulation-2 (NBIA2),' this disorder in OMIM is designated 'NBIA3.' The designation 'NBIA2' is reserved for disorders caused by mutation in the PLA2G6 gene (603604) on chromosome 22q13 (see NBIA2A, 256600 and NBIA2B, 610217).