Schizencephaly

A number sign (#) is used with this entry because evidence suggests that some patients with schizencephaly have mutations in the EMX2 (600035), SIX3 (603714), or SHH (600725) genes.

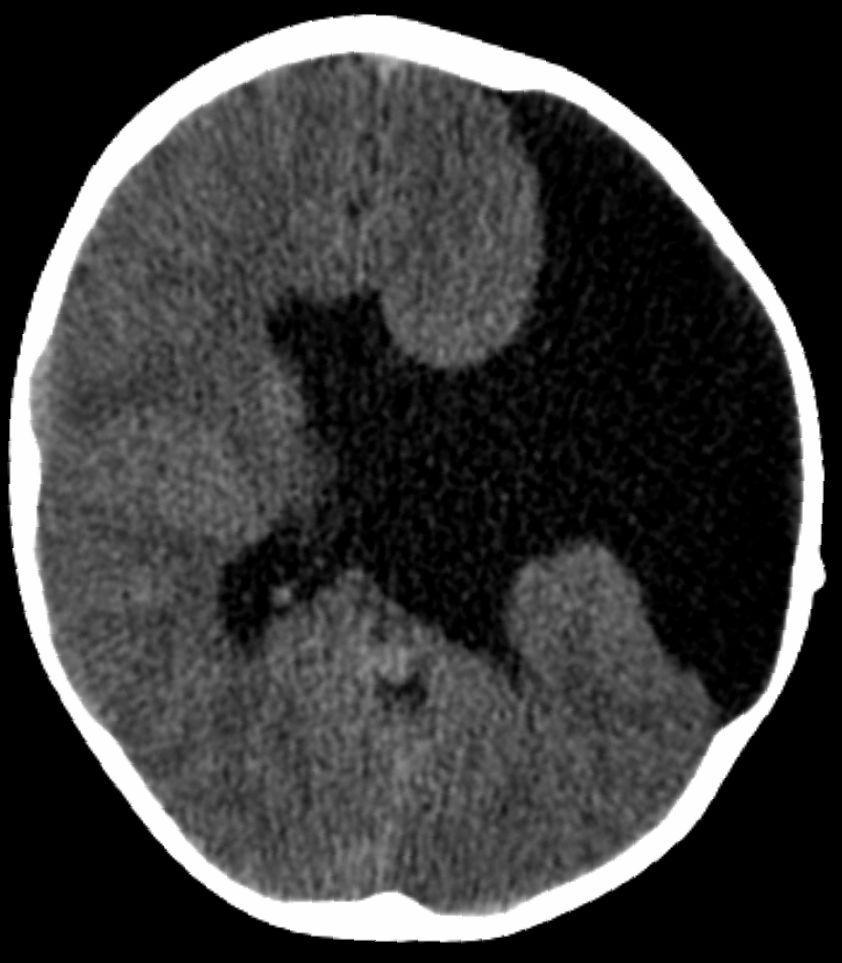

DescriptionBrunelli et al. (1996) described schizencephaly as an extremely rare congenital disorder characterized by a full-thickness cleft within the cerebral hemispheres. The clefts are lined with gray matter and most commonly involve the parasylvian regions (Wolpert and Barnes, 1992). Large portions of the cerebral hemispheres may be absent and replaced by cerebrospinal fluid. Two types of schizencephaly have been described, depending on the size of the area involved and the separation of the cleft lips (Wolpert and Barnes, 1992). Type I schizencephaly consists of a fused cleft. This fused pial-ependymal seam forms a furrow in the developing brain, and is lined by polymicrogyric gray matter. In type II schizencephaly, there is a large defect, a holohemispheric cleft in the cerebral cortex filled with fluid and lined by polymicrogyric gray matter. The clinical manifestations depend on the severity of the lesion. Patients with type I are often almost normal; they may have seizures and spasticity. In type II abnormalities, there is usually mental retardation, seizures, hypotonia, spasticity, inability to walk or speak, and blindness.

Schizencephaly may be part of the larger phenotypic spectrum of holoprosencephaly (HPE; see 236100).

Clinical FeaturesSchizencephaly is a brain malformation characterized by infolding of cortical gray matter along a hemispheric cleft near the primary cerebral fissures. The malformation was described by Yakovlev and Wadsworth (1946) who coined the term schizencephaly. Schizencephaly is thought to represent a defect in neuronal migration, i.e., a true malformation, in contrast to the porencephalies which may be encephaloclastic. Early understanding of schizencephaly was derived from pathologic specimens; subsequently, pneumoencephalography, CT, and MRI demonstrated the defects in life.

InheritanceFamilial schizencephaly was reported by Robinson (1991), Hosley et al. (1992), and Hilburger et al. (1993).

Hilburger et al. (1993) described the cases of sisters, aged 7 and 8 years, with hemiparesis and mental retardation.

Molecular GeneticsMutations in the EMX2 Gene

Brunelli et al. (1996) found that 3 of 8 patients with severe schizencephaly were heterozygous for different mutations in the EMX2 gene (600035.0001-600035.0003). The patients with EMX2 mutations belonged to the type II schizencephaly category.

Patients with mild forms of schizencephaly are often almost normal but may show partial epileptic seizures and mild spastic hemiparesis. Conversely, patients with bilateral open-lip clefts usually have microcephaly, severe developmental delay with serious mental retardation, and spastic quadriparesis. Adding to the previously reported analysis of EMX2 mutations in 7 of 8 sporadic cases of schizencephaly, Faiella et al. (1997) analyzed 10 additional patients, including 2 brothers (600035.0004). Six patients were found to be heterozygous for de novo mutations in EMX2.

Tietjen et al. (2007) sequenced the EMX2 gene in a cohort of 84 probands with schizencephaly, 53 of whom had been previously described by Curry et al. (2005), and found no pathologic mutations. The authors suggested that EMX2 mutations are an uncommon cause of schizencephaly.

Merello et al. (2008) found no mutations in the EMX2 gene in 39 patients with schizencephaly. Two of the patients were sisters, and 2 additional patients each had a family history, representing a total of 3 families in the series. Merello et al. (2008) noted that the findings of Brunelli et al. (1996) and Faiella et al. (1997), which are the same group, had never been replicated, which calls into question the validity of the findings. Merello et al. (2008) concluded that, at best, EMX2 mutations are a very rare cause of schizencephaly.

Hehr et al. (2010) also found no EMX2 mutations in 52 patients with schizencephaly, raising doubt about the functional significance of EMX2 mutations as a cause.

Mutations in the SHH Gene

Schell-Apacik et al. (2009) identified a heterozygous mutation (600725.0011) in a boy with schizencephaly and developmental delay. Brain MRI at age 5 months showed a complex brain malformation with partial absence of the corpus callosum, bilateral parietotemporal closed-lip schizencephaly, polymicrogyria, and optic atrophy. Dysmorphic features included microbrachycephaly, hypotelorism, broad nasal root, short philtrum, and a thin upper lip. The patient's unaffected mother was also heterozygous for the mutation. The findings expanded the phenotypic spectrum resulting from SHH mutations.

Mutations in the SIX3 Gene

In 2 unrelated patients and a fetus with schizencephaly, only 1 of whom also had holoprosencephaly, Hehr et al. (2010) identified 3 different heterozygous mutations in the SIX3 gene (603714.0008-603714.0010). Two of the mutations had previously been found in patients with variable manifestations of holoprosencephaly-2 (HPE2; 157170). The findings indicated that schizencephaly may be considered part of the larger phenotypic spectrum of HPE.

Population GeneticsCurry et al. (2005) reported a population-based study of schizencephaly involving 4 million births in the state of California from 1985 to 2001. The population prevalence was 1.54 in 100,000. A non-CNS abnormality was present in one-third of cases, over half of which could be classified as secondary to vascular disruption, including gastroschisis, bowel atresias, and amniotic band disruption sequence.