Chronic Granulomatous Disease

A rare primary immunodeficiency, mainly affecting phagocytes, which is characterized by an increased susceptibility to severe and recurrent bacterial and fungal infections, along with the development of granulomas.

Epidemiology

Chronic granulomatous disease (CGD) average worldwide birth prevalence is estimated between 1/100,000 and 1/217,000.

Clinical description

CGD can present at any age but is most commonly diagnosed before the age of 5 years. Manifestations include severe and recurrent infections most often due to a characteristic group of pathogens (including Staphylococcus aureus and Aspergillus spp) as well as granulomatous lesions mainly localized to the lung, lymph nodes, gastrointestinal tract and liver. Up to 50% of patients present with diarrhea, abdominal pain, and failure to thrive. Pneumonia, abscesses, cellulitis, adenitis and osteomyelitis are common. Mycobacterial diseases are usually limited to tuberculosis or regional and disseminated Bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG) infections. Invasive fungal infections are frequent. Dysregulated inflammation and granuloma formation can cause chorioretinal lesions, functional gastric outlet obstruction, inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), and wound dehiscence. Most female carriers are asymptomatic (unless >80% of their neutrophils are dysfunctional). Autoimmune disorders such as discoid lupus erythematosus and antiphospholipid syndrome can occur in some.

Etiology

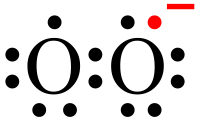

CGD is caused by mutations in any one of the 6 genes encoding the phagocyte nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) oxidase subunits or a critical stabilizer. A mutation in the CYBB gene (Xp21.1) is seen in 65% of cases in North America and Western Europe. The other 35% of cases are due to mutations in the CYBA (16q24), NCF1 (7q11.23), NCF2 (1q25), NCF4 (22q13.1) and CYBC1(17q25.3) genes. A deficiency in the NADPH oxidase enzyme complex leads to decreased production of reactive oxygen species (used by phagocytes to kill bacteria and fungi). The X-linked form of CGD typically presents with infection or IBD earlier than the NCF1-related form. To date, the NCF4-related form has only been associated with IBD but no severe infections.

Diagnostic methods

Diagnosis is suspected on clinical findings and confirmed by laboratory tests. Nitroblue tetrazolium (NBT) or dihydrorhodamine (DHR) oxidation assays measure the neutrophil superoxide production by the NADPH oxidase complex, which is absent or greatly reduced. Molecular genetic testing can be used to confirm the diagnosis and identify the specific subunit affected, but is not necessary unless gene therapy or allogeneic transplantation are anticipated. Immunoblot analysis can confirm the absence of the specific NADPH oxidase complex subunit involved.

Differential diagnosis

Differential diagnosis includes cystic fibrosis, Crohn disease, hyper-IgE syndrome, allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis, glutathione synthetase deficiency, and secondary hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Myeloperoxidase deficiency must also be excluded, as it gives a false positive for the DHR assay test.

Antenatal diagnosis

Prenatal diagnosis is possible in families with a disease-causing mutation.

Genetic counseling

CGD follows an X-linked pattern of inheritance in those with a CYBB mutation. It can also be inherited autosomal recessively (due to CYBA, NCF1, NCF2, NCF4 and CYBC1 mutations). Genetic counseling is possible in families when a disease-causing gene has been identified.

Management and treatment

Antibacterial and antifungal prophylaxis is essential in preventing the infections seen in CGD. Lifelong daily doses of trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (antibacterial) and itraconazole (anti-fungal) are recommended. Interferon-gamma, 3 times weekly, is also recommended. Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation may be curative and is increasingly used. Gene therapy has been successful in a few cases and is expanding. In those with severe infections, granulocyte transfusions are sometimes used.

Prognosis

The prognosis has greatly improved with the use of antibacterial and antifungal prophylaxis therapy, with most patients living well into adulthood.