Noise-Induced Hearing Loss

Noise-induced hearing loss (NIHL) is hearing impairment resulting from exposure to loud sound. People may have a loss of perception of a narrow range of frequencies or impaired perception of sound including sensitivity to sound or ringing in the ears. When exposure to hazards such as noise occur at work and is associated with hearing loss, it is referred to as occupational hearing loss.

Hearing may deteriorate gradually from chronic and repeated noise exposure (such as to loud music or background noise) or suddenly from exposure to impulse noise, which is a short high intensity noise (such as a gunshot or airhorn). In both types, loud sound overstimulates delicate hearing cells, leading to the permanent injury or death of the cells. Once lost this way, hearing cannot be restored in humans.

There are a variety of prevention strategies available to avoid or reduce hearing loss. Lowering the volume of sound at its source, limiting the time of exposure and physical protection can reduce the impact of excessive noise. If not prevented, hearing loss can be managed through assistive devices and communication strategies.

The largest burden of NIHL has been through occupational exposures; however, noise-induced hearing loss can also be due to unsafe recreational, residential, social and military service-related noise exposures. It is estimated that 15% of young people are exposed to sufficient leisure noises (i.e. concerts, sporting events, daily activities, personal listening devices, etc.) to cause NIHL. There is not a limited list of noise sources that can cause hearing loss; rather, exposure to excessively high levels from any sound source over time can cause hearing loss.

Signs and symptoms

The first symptom of NIHL may be difficulty hearing a conversation against a noisy background. The effect of hearing loss on speech perception has two components. The first component is the loss of audibility, which may be perceived as an overall decrease in volume. Modern hearing aids compensate this loss with amplification. The second component is known as "distortion" or "clarity loss" due to selective frequency loss. Consonants, due to their higher frequency, are typically affected first. For example, the sounds "s" and "t" are often difficult to hear for those with hearing loss, affecting clarity of speech. NIHL can affect either one or both ears. Unilateral hearing loss causes problems with directional hearing, affecting the ability to localize sound.

Temporary and permanent hearing changes

- PTS (Permanent Threshold Shift) is a permanent change of the hearing threshold (the intensity necessary for one to detect a sound) following an event, which will never recover. PTS is measured in decibels.

- TTS (Temporary Threshold Shift) is a temporary change of the hearing threshold the hearing loss that will be recovered after a few hours to couple of days. Also called auditory fatigue. TTS is also measured in decibels.

In addition to hearing loss, other external symptoms of an acoustic trauma can be:

- Tinnitus

- Otalgia

- Hyperacusis

- Dizziness or vertigo; in the case of vestibular damages, in the inner-ear

Tinnitus

Tinnitus is described as hearing a sound when an external sound is not present. Noise-induced hearing loss can cause high-pitched tinnitus. An estimated 50 million Americans have some degree of tinnitus in one or both ears; 16 million of them have symptoms serious enough for them to see a doctor or hearing specialist. As many as 2 million become so debilitated by the unrelenting ringing, hissing, chirping, clicking, whooshing or screeching, that they cannot carry out normal daily activities.

Tinnitus is the largest single category for disability claims in the military, with hearing loss a close second. The third largest category is post-traumatic stress disorder, which itself may be accompanied by tinnitus and may exacerbate it.

Quality of life

NIHL has implications on quality of life that extend beyond related symptoms and the ability to hear. The annual disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) were estimated for noise-exposed U.S. workers.[20] DALYs represent the number of healthy years lost due to a disease or other health condition. They were defined by the 2013 Global Burden of Disease (GBD) Study. The DALYs calculation accounts for life limitations experienced because of hearing loss as a lost portion of a healthy year of life. So the results indicate the number of healthy years lost by a group of people over a specific time period.

NIOSH used DALYs to estimate the impact of hearing loss on quality of life in the CDC Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report article "Hearing Impairment Among Noise-Exposed Workers in the United States, 2003-2012." It reported that 2.5 healthy years were lost each year for every 1,000 noise-exposed U.S. workers because of hearing impairment (hearing loss that impacts day-to-day activities). These lost years were shared among the 13% of workers with hearing impairment (about 130 workers out of each 1,000 workers). Mining, Construction and Manufacturing workers lost more healthy years than workers in other industry sectors; specifically and respectively in those sectors, 3.5, 3.1 and 2.7 healthy years were lost each year for every 1,000 workers.

Negative impacts

The negative impacts of NIHL on one's ability to reciprocate communication, socialize and interact with society are largely invisible. Hearing loss, in general, is not just an issue of volume; individuals may experience difficulty in understanding what is said over the phone, when several people are talking at once, in a large space, or when the speaker's face cannot be seen. Subsequently, challenging social interactions can negatively lead to decreased self-esteem, shame, and fear. This can be more acutely felt by those who experience hearing impairment or loss earlier in life, rather than later when it is more socially accepted. Such psychosocial states, regardless of age, can lead to social isolation, which is known to negatively impact one's overall health and well-being. The compounding impacts can also lead to depression, especially if hearing impairment leads to tinnitus. Research suggests that those with hearing impairment or loss may be at a greater risk for deterioration of quality of life, as captured by a quote from Helen Keller: "Blindness cuts us off from things, but deafness cuts us off from people." Hearing impairment and loss of hearing, regardless of source or age, also limits experiencing the many benefits of sound on quality of life. In addition to the interpersonal social benefits, new studies suggest the effects of nature sounds, such as birds chirping and water, can positively affect an individual's capacity to recover after being stressed or to increase cognitive focus.

Quality of life questionnaire

Hearing loss is typically quantified by results from an audiogram; however, the degree of loss of hearing does not predict the impact on one's quality of life. The impact that NIHL can have on daily life and psychosocial function can be assessed and quantified using a validated questionnaire tool, such as the Hearing Handicap Inventory for the Elderly (HHIE). The HHIE is considered a "useful tool for quantifying the perceived emotional and social/situational consequences of hearing loss." The original tool was designed to test adults 65 years of age and older; however, modified versions exist. For adults the Hearing Handicap Inventory for Adults (HHIA) can be used and for adolescents the modified 28-item Hearing Environments And Reflection on Quality of Life (HEAR-QL-28) can be used. The HHIA, for example, is a 25-item questionnaire that asks both social and emotional-specific questions such as: Does a hearing problem cause you to avoid groups of people?" (social) and "Does a hearing problem cause you to feel frustrated when talking to members of your family?" (emotional). Response options are yes, no and sometimes. A greater score indicates greater perceived handicap.

Cause

The ear can be exposed to short periods of sound in excess of 120 dB without permanent harm — albeit with discomfort and possibly pain; but long term exposure to sound levels over 85 dB(A) can cause permanent hearing loss.

There are two basic types of NIHL:

- NIHL caused by acoustic trauma and

- gradually developing NIHL.

Acute acoustic trauma

NIHL caused by acute acoustic trauma refers to permanent cochlear damage from a one-time exposure to excessive sound pressure. This form of NIHL commonly results from exposure to high-intensity sounds such as explosions, gunfire, a large drum hit loudly, and firecrackers. According to one US study, excessive noise levels in cinemas are sufficiently brief that movie-goers do not experience hearing loss.

Perceived harmfulness vs. actual harmfulness

The discomfort threshold is the loudness level from which a sound starts to be felt as too loud and thus painful by an individual. Industry workers tend to have a higher discomfort threshold (i.e. the sounds must be louder to feel painful than for non-industry workers), but the sound is just as harmful to their ears. Industry workers often suffer from NIHL because the discomfort threshold is not a relevant indicator of the harmfulness of a sound.

Gradually developing

Gradually developing NIHL refers to permanent cochlear damage from repeated exposure to loud sounds over a period of time. Unlike acoustic trauma, this form of NIHL does not occur from a single exposure to a high-intensity sound pressure level. Gradually developing NIHL can be caused by multiple exposures to excessive noise in the workplace or any source of repetitive, frequent exposures to sounds of excessive volume, such as home and vehicle stereos, concerts, nightclubs, and personal media players. Earplugs have been recommended for those people who regularly attend live music concerts. A range of earplugs are now available ranging from inexpensive disposable sets to custom fit, attenuated earplugs which provide true fidelity at reduced audio levels.

Personal listening devices

Although research is limited, it suggests that increased exposure to loud noise through personal listening devices is a risk factor for noise induced hearing loss. More than half of people are exposed to sound through music exposure on personal devices greater than recommended levels. Research suggests stronger correlations between extended duration or elevated usage of personal listening devices and hearing loss.

Workplace

About 22 million workers are exposed to hazardous noise, with additional millions exposed to solvents and metals that could put them at increased risk for hearing loss. Occupational hearing loss is one of the most common occupational diseases. 49% of male miners have hearing loss by the age of 50. By the age of 60, this number goes up to 70%. Construction workers also suffer an elevated risk. A screening program focused on construction workers employed at US Department of Energy facilities found 58% with significant abnormal hearing loss due to noise exposures at work. Occupational hearing loss is present in up to 33% of workers overall. Occupational exposure to noise causes 16% of adult disabling hearing loss worldwide.

The following is a list of occupations that are most susceptible to hearing loss:

- Agriculture

- Mining

- Construction

- Manufacturing

- Utilities

- Transportation

- Military

- Musicians

- Orchestra conductors

Among musicians

Musicians, from classical orchestras to rock groups, are exposed to high decibel ranges. Some rock musicians experience noise-induced hearing loss from their music, and some studies have found that "symphonic musicians suffer from hearing impairment and that the impairment might be ascribed to symphonic music."

In terms of the population of musicians, usually the rates of hearing disorders is lower than other occupational groups. However, many exposure scenarios can be considered a risk of hearing disorders, and many individuals are negatively impacted by tinnitus and other hearing problems. While some population studies have shown that the risk for hearing loss increases as music exposure increases, other studies found little to no correlation between the two. Experts at the 2006 "Noise-Induced Hearing Loss in Children at Work and Play" Conference agreed that further research into this field was still required before making a broad generalization about music-induced hearing loss.

Given the extensive research suggesting that industrial noise exposure can cause sensorineural hearing loss, a link between hearing loss and music exposures of similar level and duration (to industrial noise) seems highly plausible. Determining which individuals or groups are at risk for such exposures may be a difficult task. Despite concerns about the proliferation of personal music players, there is only scarce evidence supporting their impact on hearing loss, and some small-sample studies suggest that only a fraction of users are affected. People from ages to 6–19 have an approximately 15% rate of hearing loss. Recommendations for musicians to protect their hearing were released in 2015 by NIOSH. The recommendations emphasized education of musicians and those who work in or around the music industry. Annual hearing assessments were also recommended to monitor thresholds as were sound level assessments to help determine the amount of time musicians and related professionals should spend in that environment. Hearing protection was also recommended, and the authors of the NIOSH recommendations even suggested that musicians consider custom earplugs as a way to combat NIHL. Despite these recommendations, musicians continue to face unique challenges in protecting their hearing when compared to individuals in industrial settings. Typically environmental controls are the first line of defense in a hearing conservation program, and depending on the type of musicians some recommendations have been set in place. These recommendations can include adjusting risers or level of the speakers and adjusting the layout of a band or orchestra. These changes in the environment can be beneficial to musicians, but the ability to accomplish them is not always possible. In the cases where these changes cannot be made, hearing protection is recommended. Hearing protection in musicians offers its own sets of benefits and complications. When used properly, hearing protection can limit the exposure of noise in individuals. Musicians have the ability to pick from several different types of hearing protection from conventional ear plugs to custom or high fidelity hearing protection. Despite this, use of hearing protection among musicians is low for several different reasons. Musicians often feel that hearing protective devices can distort how music sounds or makes it too quiet for them to hear important cues which makes them less likely to wear hearing protection even when aware of the risks. Research suggests that educations programs can be beneficial to musicians as well as working with hearing care professionals to help address the specific issues that musicians face.[1]

In 2018, a musician named Chris Goldscheider won a case against Royal Opera House for damaging his hearing in a rehearsal of Wagner's thunderous opera Die Walkure.

Workplace standards

In the United States, the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) describes standards for occupational noise exposure in articles 1910.95 and 1926.52. OSHA states that an employer must implement hearing conservation programs for employees if the noise level of the workplace is equal to or above 85 dB(A) for an averaged eight-hour time period. OSHA also states that "exposure to impulsive or impact noise should not exceed 140 dB peak sound pressure level". The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) recommends that all worker exposures to noise should be controlled below a level equivalent to 85 dBA for eight hours to minimize occupational noise induced hearing loss. NIOSH also recommends a 3 dBA exchange rate so that every increase by 3 dBA doubles the amount of the noise and halves the recommended amount of exposure time. The United States Department of Defense (DoD) instruction 605512 has some differences from OSHA 1910.95 standard, for example, OSHA 1910.95 uses a 5 dB exchange rate and DoD instruction 605512 uses a 3 dB exchange rate.

There are programs that seek to increase compliance and therefore effectiveness of hearing protection rules; the programs include the use of hearing tests and educating people that loud sound is dangerous

Employees are required to wear hearing protection when it is identified that their eight-hour time weighted average (TWA) is above the exposure action value of 90 dB. If subsequent monitoring shows that 85 dB is not surpassed for an eight-hour TWA, the employee is no longer required to wear hearing protection.

In the European Union, directive 2003/10/EC mandates that employers shall provide hearing protection at noise levels exceeding 80 dB(A), and that hearing protection is mandatory for noise levels exceeding 85 dB(A). Both values are based on 8 hours per day, with a 3 dB exchange rate.

A 2017 Cochrane review found low-quality evidence that legislation to reduce noise in the workplace was successful in reducing exposure both immediately and long-term.

Sporting events

Several sports stadiums pride themselves in having louder stadiums than their opponents because it may create a more difficult environment for opposing teams to play in. Currently, there are few studies on noise in sports stadiums, but some preliminary measurements show noise levels reaching 120 dB, and informal studies suggest that people may receive up to a 117% noise dose in one game. There are many challenges that face hearing conservationists such as sports culture. Sports fans will create noise in an attempt to distract other teams, and some sports teams have been known to create artificial noise in an attempt to make the stadium louder. In doing that, workers, teams, and fans may be at potential risk for damage to the auditory system.

NIOSH conducted a health hazard evaluation and studies at Monster Trucking and Stock Car racing events, spectators average noise levels ranged from 95 to 100 dBA at the Monster Truck event and over 100 dBA at the stock car racing event. NIOSH researchers also published noise exposure levels for drivers, crew members, and staff. Noise levels at the Bristol Motor Speedway ranged from 96 dBA in the stands to 114 dBA for a driver inside a car during practice. Peak noise levels in the Pit area reached or exceeded 130 dB SPL, a level often associated with human hearing threshold for pain. Several prominent NASCAR drivers have complete or partial hearing loss and other symptoms from their many years of exposure.

During the FIFA World Cup in 2010, noise levels created by fans blowing Vuvuzela averaged 131 dBA at the horn opening and 113 dBA at 2 meter distance. Peak levels reached 144 dB SPL, louder than a jet engine at takeoff.

A study of occupational and recreational noise exposure at indoor hockey arenas found noise levels from 81 dBA to 97 dBA, with peak sound pressure levels ranging from 105 dB SPLto 124 dB SPL. Another study examined the hearing threshold of hockey officials and found mean noise exposures of 93 dBA. Hearing threshold shifts were observed in 86% of the officials (25/29).

In a study of noise levels at 10 intercollegiate basketball games showed noise levels in 6 of the 10 basketball games to exceed the national workplace noise exposure standards, with participants showing temporary threshold levels at one of the games.

While there is no agency that currently monitors sports stadium noise exposure, organizations such as NIOSH or OSHA use occupational standards for industrial settings that some experts feel could be applied for those working at sporting events. Workers often will not exceed OSHA standards of 90 dBA, but NIOSH, whose focus is on best practice, has stricter standards which say that when exposed to noise at or exceeding 85 dBA workers need to be put on a hearing conservation program. Workers may also be at risk for overexposure because of impact noises that can cause instant damage. Experts are suggesting that sports complexes create hearing conservation programs for workers and warn fans of the potential damage that may occur with their hearing.

Studies are still being done on fan exposure, but some preliminary findings show that there are often noises that can be at or exceed 120 dB which, unprotected, can cause damage to the ears in seconds.

Mechanisms

Play media

Play media

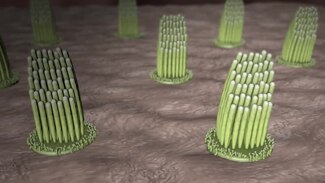

NIHL occurs when too much sound intensity is transmitted into and through the auditory system. An acoustic signal from a sound source, such as a radio, enters into the external auditory canal (ear canal), and is funneled through to the tympanic membrane (eardrum), causing it to vibrate. The vibration of the tympanic membrane drives the middle ear ossicles, the malleus, incus, and stapes to vibrate in sync with the eardrum. The middle ear ossicles transfer mechanical energy to the cochlea by way of the stapes footplate hammering against the oval window of the cochlea, effectively amplifying the sound signal. This hammering causes the fluid within the cochlea (perilymph and endolymph) to be displaced. Displacement of the fluid causes movement of the hair cells (sensory cells in the cochlea) and an electrochemical signal to be sent from the auditory nerve (CN VIII) to the central auditory system within the brain. This is where sound is perceived. Different groups of hair cells are responsive to different frequencies. Hair cells at or near the base of the cochlea are most sensitive to higher frequency sounds while those at the apex are most sensitive to lower frequency sounds. There are two known biological mechanisms of NIHL from excessive sound intensity: damage to the structures called stereocilia that sit atop hair cells and respond to sound, and damage to the synapses that the auditory nerve makes with hair cells, also termed "hidden hearing loss".

Physiological response

The symptoms mentioned above are the external signs of the physiological response to cochlear overstimulation. Here are some elements of this response:

- Damaged sensory hairs (stereocilia) of the hair cells; damaged hair cells degenerate and die. In humans and other mammals, dead hair-cells are never replaced; the resulting hearing loss is permanent.

- Inflammation of the exposed areas. This inflammation causes poor blood flow in the exposed blood vessels (vascular stasis), and poor oxygen supply for the liquid inside the cochlea (endolymphatic hypoxia) Those noxious conditions worsen the damaged hair cell degeneration.

- Synaptic damages, by excitotoxicity. Noise over-stimulation causes an excessive release of glutamate, causing the postsynaptic bouton to swell and burst. However the neuron connection can be repaired, and the hearing loss only caused by the "wiring" (i.e. excitotoxicity) can thus be recovered within 2–3 days.

Hair cell damage or death

When the ear is exposed to excessive sound levels or loud sounds over time, the overstimulation of the hair cells leads to heavy production of reactive oxygen species, leading to oxidative cell death. In animal experiments, antioxidant vitamins have been found to reduce hearing loss even when administered the day after noise exposure. They were not able to fully prevent it. Damage ranges from exhaustion of the hair (hearing) cells in the ear to loss of those cells. NIHL is, therefore, the consequence of overstimulation of the hair cells and supporting structures. Structural damage to hair cells (primarily the outer hair cells) will result in hearing loss that can be characterized by an attenuation and distortion of incoming auditory stimuli.

During hair cell death ‘scars’ develop, which prevent potassium rich fluid of the endolymph from mixing with the fluid on the basal domain. The potassium rich fluid is toxic to the neuronal endings and can damage hearing of the entire ear. If the endolymph fluid mixes with the fluid on the basal domain the neurons become depolarized, causing complete hearing loss. In addition to complete hearing loss, if the area is not sealed and leakage continues further tissue damage will occur. The ‘scars’ that form to replace the damaged hair cell are caused by supporting hair cells undergoing apoptosis and sealing the reticular lamina, which prevents fluid leakage. The cell death of two supporting hair cells rapidly expands their apical domain, which compresses the hair cell beneath its apical domain.

Nerve damage

Recent studies have investigated additional mechanisms of NIHL involving delayed or disabled electrochemical transmission of nerve impulses from the hair cell to and along the auditory nerve. In cases of extreme acute acoustic trauma, a portion of the postsynaptic dendrite (where the hair cell transfers electrochemical signals to the auditory nerve) can rupture from overstimulation, temporarily stopping all transmission of auditory input to the auditory nerve. This is known as excitotoxicity. Usually, this sort of rupture heals within about five days, resulting in functional recovery of that synapse. While healing, an over-expression of glutamate receptors can result in temporary tinnitus, or ringing in the ears. Repeated ruptures at the same synapse may eventually fail to heal, leading to permanent hearing loss.

Prolonged exposure to high intensity noise has also been linked to the disruption of ribbon synapses located in the synaptic cleft between inner hair cells and spiral ganglion nerve fibers, leading to a disorder referred to as cochlear synaptopathy or hidden hearing loss. This disorder is cumulative and over time, leads to degeneration of the spiral ganglion cells of the inner ear and overall dysfunction in the neural transmission between auditory nerve fibers and the central auditory pathway. The most common symptom of cochlear synaptopathy is difficulty understanding speech, especially in the presence of competing noise. However, this type of hearing impairment is often undetectable by conventional pure tone audiometry, thus the name "hidden" hearing loss.

Acoustic over-exposure can also result in decreased myelination at specific points on the auditory nerve. Myelin, an insulating sheath surrounding nerve axons, expedites electrical impulses along nerves throughout the nervous system. Thinning of the myelin sheath on the auditory nerve significantly slows the transmission of electrical signals from hair cell to auditory cortex, reducing comprehension of auditory stimuli by delaying auditory perception, particularly in noisy environments.

Individual susceptibility towards noise

There appear to be large differences in individual susceptibility to NIHL. The following factors have been implicated:

- missing acoustic reflex

- previous sensorineural hearing loss

- a bad general health state: bad cardiovascular function, insufficient intake of oxygen, a high platelet aggregation rate; and most importantly, a high viscosity of the blood

- cigarette smoking

- exposure to ototoxic chemicals (medication or environmental chemicals that can damage the ear), including certain solvents and heavy metals

- type 2 diabetes

Diagnosis

Both NIHL caused by acoustic trauma and gradually-developed-NIHL can often be characterized by a specific pattern presented in audiological findings. NIHL is generally observed to decrease hearing sensitivity in the higher frequencies, also called an audiometric notch, especially at 4000 Hz, but sometimes at 3000 or 6000 Hz. The symptoms of NIHL are usually presented equally in both ears.

This typical 4000 Hz notch is due to the transfer function of the ear. As does any object facing a sound, the ear acts as a passive filter, although the inner ear is not an absolute passive filter because the outer hair cells provide active mechanisms. A passive filter is a low pass: the high frequencies are more absorbed by the object because high frequencies impose a higher pace of compression-decompression to the object. The high frequency harmonics of a sound are more harmful to the inner-ear.

However, not all audiological results from people with NIHL match this typical notch. Often a decline in hearing sensitivity will occur at frequencies other than at the typical 3000–6000 Hz range. Variations arise from differences in people's ear canal resonance, the frequency of the harmful acoustic signal, and the length of exposure. As harmful noise exposure continues, the commonly affected frequencies will broaden to lower frequencies and worsen in severity.

Prevention

Play media

Play mediaNIHL can be prevented through the use of simple, widely available, and economical tools. This includes but is not limited to personal noise reduction through the use of ear protection (i.e. earplugs and earmuffs), education, and hearing conservation programs. For the average person, there are three basic things that one can do to prevent NIHL: turn down the volume on devices, move away from the source of noise, and wear hearing protectors in loud environments.

Non-occupational noise exposure is not regulated or governed in the same manner as occupational noise exposure; therefore prevention efforts rely heavily on education awareness campaigns and public policy. The WHO cites that nearly half of those affected by hearing loss could have been prevented through primary prevention efforts such as: "reducing exposure (both occupational and recreational) to loud sounds by raising awareness about the risks; developing and enforcing relevant legislation; and encouraging individuals to use personal protective devices such as earplugs and noise-cancelling earphones and headphones."

Personal noise reduction devices

Personal noise reduction devices can be passive, active or a combination. Passive ear protection includes earplugs or earmuffs which can block noise up to a specific frequency. Earplugs and earmuffs can provide the wearer with 10 dB to 40 dB of attenuation. However, use of earplugs is only effective if the users have been educated and use them properly; without proper use, protection falls far below manufacturer ratings. A Cochrane review found that training of earplug insertion can reduce noise exposure at short term follow-up compared to workers wearing earplugs without training. Higher consistency of performance has been found with custom-molded earplugs. Because of their ease of use without education, and ease of application or removal, earmuffs have more consistency with both compliance and noise attenuation. Active ear protection (electronic pass-through hearing protection devices or EPHPs) electronically filter out noises of specific frequencies or decibels while allowing the remaining noise to pass through. A personal attenuation rating can be objectively measured by using a hearing protection fit testing system.

Education

Education is key to prevention. Before hearing protective actions will take place, a person must understand they are at risk for NIHL and know their options for prevention. Hearing protection programs have been hindered by people not wearing the protection for various reasons, including the desire to converse, uncomfortable devices, lack of concern about the need for protection, and social pressure against wearing protection. Although youth are at risk for hearing loss, one study found that 96.3% of parents did not believe their adolescents were at risk, and only 69% had talked to their children about hearing protection; those aware of NIHL risks were more likely to talk to their teens.

A systematic review of the effectiveness of interventions to promote the use of hearing protection devices such as earplugs and earmuffs among workers found that tailored interventions improve the average use of such devices when compared with no intervention. Tailored interventions involve the use of communication or other types of interventions that are specific to an individual or a group and aim to change behavior. Mixed interventions such as mailings, distribution of hearing protection devices, noise assessments, and hearing testing are also more effective in improving the use of hearing protection devices compared with hearing testing alone. Programs that increased the proportion of workers wearing hearing protection equipment did reduce overall hearing loss.

Hearing conservation programs

Workers in general industry who are exposed to noise levels above 85 dBA are required by the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) to be in a hearing conservation program (HCP), which includes noise measurement, noise control, periodic audiometric testing, hearing protection, worker education, and record keeping. Twenty-four states, Puerto Rico, and the U.S. Virgin Islands have OSHA-approved state plans and have adopted their own standards and enforcement policies. Most of these state standards are identical to those of federal OSHA. However, some states have adopted different standards or may have different enforcement policies. Most health and safety regulations are designed to keep damage risk within "acceptable limits" — that is, some people are likely to incur a hearing loss even when exposed to less than the maximum daily amount of noise specified in a regulation. Hearing conservation programs in other arenas (schools, military) have become more common, and it has been established that unsafe listening behaviors, such as listening to loud noise for extended periods of time without protection, persist despite knowledge of potential hearing loss effects.

However, it is understood that HCPs are designed to change behavior, which is known to be a complex issue that requires a multi-faceted approach. According to Keppler et al. in their 2015 study of such programming, they cite the necessary attitude change towards the susceptibility of risk and degree of severity of hearing loss. Among young adults, the concept of severity is most crucial because it has been found that behavior change may not occur unless an individual experiences NIHL or similarly related NIHL tinnitus, furthering warranting a multi-pronged approach based on hearing conservation programming and education.

Interventions to prevent noise-induced hearing loss often have many components. A 2017 Cochrane review found that hearing loss prevention programs suggest that stricter legislation might reduce noise levels. Giving workers information on their noise exposure levels by itself was not shown to decrease exposure to noise. Ear protection, if used correctly, has the potential to reduce noise to safer levels, but does not necessarily prevent hearing loss. External solutions such as proper maintenance of equipment can lead to noise reduction, but further study of this issue under real-life conditions is needed. Other possible solutions include improved enforcement of existing legislation and better implementation of well-designed prevention programmes, which have not yet been proven conclusively to be effective. The implications is that further research could affect conclusions reached.

Several hearing conservation programs have been developed to educate a variety of audiences about the dangers of NIHL and how to prevent it. Dangerous Decibels aims to significantly reduce the prevalence of noise induced hearing loss and tinnitus through exhibits, education and research. We’re hEAR for You is a small non-profit that distributes information and ear plugs at concert and music festival venues. The Buy Quiet program was created to combat occupational noise exposures by promoting the purchase of quieter tools and equipment and encourage manufacturers to design quieter equipment. The National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders developed the It's a Noisy Planet. Protect their Hearing educational campaign to inform preteens, parents, and educators about the causes and prevention of NIHL. The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health partnered with the National Hearing Conservation Association in 2007 to establish the Safe-in-Sound Excellence and Innovation in Hearing Loss Prevention Awards to recognize organizations that are successfully implementing hearing loss prevention concepts into their daily routines.

Medication

Medications are still being researched to determine if they can prevent NIHL. No medication has been proven to prevent or repair NIHL in humans.

There is evidence that hearing loss can be minimized by taking high doses of magnesium for a few days, starting as soon as possible after exposure to the loud noise. A magnesium-high diet also seems to be helpful as an NIHL-preventative if taken in advance of exposure to loud noises