Osteoarthritis

Osteoarthritis (OA) is a type of joint disease that results from breakdown of joint cartilage and underlying bone. The most common symptoms are joint pain and stiffness. Usually the symptoms progress slowly over years. Initially they may occur only after exercise but can become constant over time. Other symptoms may include joint swelling, decreased range of motion, and, when the back is affected, weakness or numbness of the arms and legs. The most commonly involved joints are the two near the ends of the fingers and the joint at the base of the thumbs; the knee and hip joints; and the joints of the neck and lower back. Joints on one side of the body are often more affected than those on the other. The symptoms can interfere with work and normal daily activities. Unlike some other types of arthritis, only the joints, not internal organs, are affected.

Causes include previous joint injury, abnormal joint or limb development, and inherited factors. Risk is greater in those who are overweight, have legs of different lengths, or have jobs that result in high levels of joint stress. Osteoarthritis is believed to be caused by mechanical stress on the joint and low grade inflammatory processes. It develops as cartilage is lost and the underlying bone becomes affected. As pain may make it difficult to exercise, muscle loss may occur. Diagnosis is typically based on signs and symptoms, with medical imaging and other tests used to support or rule out other problems. In contrast to rheumatoid arthritis, in osteoarthritis the joints do not become hot or red.

Treatment includes exercise, decreasing joint stress such as by rest or use of a cane, support groups, and pain medications. Weight loss may help in those who are overweight. Pain medications may include paracetamol (acetaminophen) as well as NSAIDs such as naproxen or ibuprofen. Long-term opioid use is not recommended due to lack of information on benefits as well as risks of addiction and other side effects. Joint replacement surgery may be an option if there is ongoing disability despite other treatments. An artificial joint typically lasts 10 to 15 years.

Osteoarthritis is the most common form of arthritis, affecting about 237 million people, or 3.3% of the world's population. In the United States, 30 to 53 million people are affected, and in Australia, about 1.9 million people are affected. It becomes more common as people become older. Among those over 60 years old, about 10% of males and 18% of females are affected. Osteoarthritis is the cause of about 2% of years lived with disability.

Signs and symptoms

The main symptom is pain, causing loss of ability and often stiffness. The pain is typically made worse by prolonged activity and relieved by rest. Stiffness is most common in the morning, and typically lasts less than thirty minutes after beginning daily activities, but may return after periods of inactivity. Osteoarthritis can cause a crackling noise (called "crepitus") when the affected joint is moved, especially shoulder and knee joint. A person may also complain of joint locking and joint instability. These symptoms would affect their daily activities due to pain and stiffness. Some people report increased pain associated with cold temperature, high humidity, or a drop in barometric pressure, but studies have had mixed results.

Osteoarthritis commonly affects the hands, feet, spine, and the large weight-bearing joints, such as the hips and knees, although in theory, any joint in the body can be affected. As osteoarthritis progresses, movement patterns (such as gait), are typically affected. Osteoarthritis is the most common cause of a joint effusion of the knee.

In smaller joints, such as at the fingers, hard bony enlargements, called Heberden's nodes (on the distal interphalangeal joints) or Bouchard's nodes (on the proximal interphalangeal joints), may form, and though they are not necessarily painful, they do limit the movement of the fingers significantly. Osteoarthritis of the toes may be a factor causing formation of bunions, rendering them red or swollen.

Causes

Damage from mechanical stress with insufficient self repair by joints is believed to be the primary cause of osteoarthritis. Sources of this stress may include misalignments of bones caused by congenital or pathogenic causes; mechanical injury; excess body weight; loss of strength in the muscles supporting a joint; and impairment of peripheral nerves, leading to sudden or uncoordinated movements. However exercise, including running in the absence of injury, has not been found to increase the risk of knee osteoarthritis. Nor has cracking one's knuckles been found to play a role.

Primary

The development of osteoarthritis is correlated with a history of previous joint injury and with obesity, especially with respect to knees. Changes in sex hormone levels may play a role in the development of osteoarthritis, as it is more prevalent among post-menopausal women than among men of the same age. Conflicting evidence exists for the differences in hip and knee osteoarthritis in African American and Caucasians.

Occupational

Increased risk of developing knee and hip osteoarthritis was found among those who work with manual handling (e.g. lifting), have physically demanding work, walk at work, and have climbing tasks at work (e.g. climb stairs or ladders). With hip osteoarthritis in particular, increased risk of development over time was found among those who work in bent or twisted positions. For knee osteoarthritis in particular, increased risk was found among those who work in a kneeling or squatting position, experience heavy lifting in combination with a kneeling or squatting posture, and work standing up. Women and men have similar occupational risks for the development of osteoarthritis.

Secondary

This type of osteoarthritis is caused by other factors but the resulting pathology is the same as for primary osteoarthritis:

- Alkaptonuria

- Congenital disorders of joints

- Diabetes doubles the risk of having a joint replacement due to osteoarthritis and people with diabetes have joint replacements at a younger age than those without diabetes.

- Ehlers-Danlos syndrome

- Hemochromatosis and Wilson's disease

- Inflammatory diseases (such as Perthes' disease), (Lyme disease), and all chronic forms of arthritis (e.g., costochondritis, gout, and rheumatoid arthritis). In gout, uric acid crystals cause the cartilage to degenerate at a faster pace.

- Injury to joints or ligaments (such as the ACL), as a result of an accident or orthopedic operations.

- Ligamentous deterioration or instability may be a factor.

- Marfan syndrome

- Obesity

- Joint infection

Pathophysiology

While osteoarthritis is a degenerative joint disease that may cause gross cartilage loss and morphological damage to other joint tissues, more subtle biochemical changes occur in the earliest stages of osteoarthritis progression. The water content of healthy cartilage is finely balanced by compressive force driving water out and hydrostatic and osmotic pressure drawing water in. Collagen fibres exert the compressive force, whereas the Gibbs–Donnan effect and cartilage proteoglycans create osmotic pressure which tends to draw water in.

However, during onset of osteoarthritis, the collagen matrix becomes more disorganized and there is a decrease in proteoglycan content within cartilage. The breakdown of collagen fibers results in a net increase in water content. This increase occurs because whilst there is an overall loss of proteoglycans (and thus a decreased osmotic pull), it is outweighed by a loss of collagen. Without the protective effects of the proteoglycans, the collagen fibers of the cartilage can become susceptible to degradation and thus exacerbate the degeneration. Inflammation of the synovium (joint cavity lining) and the surrounding joint capsule can also occur, though often mild (compared to the synovial inflammation that occurs in rheumatoid arthritis). This can happen as breakdown products from the cartilage are released into the synovial space, and the cells lining the joint attempt to remove them.

Other structures within the joint can also be affected. The ligaments within the joint become thickened and fibrotic and the menisci can become damaged and wear away. Menisci can be completely absent by the time a person undergoes a joint replacement. New bone outgrowths, called "spurs" or osteophytes, can form on the margins of the joints, possibly in an attempt to improve the congruence of the articular cartilage surfaces in the absence of the menisci. The subchondral bone volume increases and becomes less mineralized (hypomineralization). All these changes can cause problems functioning. The pain in an osteoarthritic joint has been related to thickened synovium and to subchondral bone lesions.

Diagnosis

| Type | WBC per mm3 | % neutrophils | Viscosity | Appearance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal | <200 | 0 | High | Transparent |

| Osteoarthritis | <5000 | <25 | High | Clear yellow |

| Trauma | <10,000 | <50 | Variable | Bloody |

| Inflammatory | 2,000-50,000 | 50-80 | Low | Cloudy yellow |

| Septic arthritis | >50,000 | >75 | Low | Cloudy yellow |

| Gonorrhea | ~10,000 | 60 | Low | Cloudy yellow |

| Tuberculosis | ~20,000 | 70 | Low | Cloudy yellow |

| Inflammatory = gout, rheumatoid arthritis, rheumatic fever | ||||

Diagnosis is made with reasonable certainty based on history and clinical examination. X-rays may confirm the diagnosis. The typical changes seen on X-ray include: joint space narrowing, subchondral sclerosis (increased bone formation around the joint), subchondral cyst formation, and osteophytes. Plain films may not correlate with the findings on physical examination or with the degree of pain. Usually other imaging techniques are not necessary to clinically diagnose osteoarthritis.

In 1990, the American College of Rheumatology, using data from a multi-center study, developed a set of criteria for the diagnosis of hand osteoarthritis based on hard tissue enlargement and swelling of certain joints. These criteria were found to be 92% sensitive and 98% specific for hand osteoarthritis versus other entities such as rheumatoid arthritis and spondyloarthropathies.

Severe osteoarthritis and osteopenia of the carpal joint and 1st carpometacarpal joint.

MRI of osteoarthritis in the knee, with characteristic narrowing of the joint space.

Primary osteoarthritis of the left knee. Note the osteophytes, narrowing of the joint space (arrow), and increased subchondral bone density (arrow).

Damaged cartilage from sows. (a) cartilage erosion (b)cartilage ulceration (c)cartilage repair (d)osteophyte (bone spur) formation.

Histopathology of osteoarthrosis of a knee joint in an elderly female.

Histopathology of osteoarthrosis of a knee joint in an elderly female.

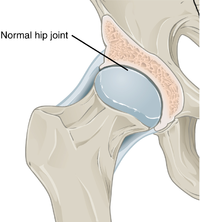

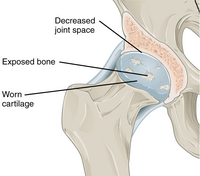

In a healthy joint, the ends of bones are encased in smooth cartilage. Together, they are protected by a joint capsule lined with a synovial membrane that produces synovial fluid. The capsule and fluid protect the cartilage, muscles, and connective tissues.

With osteoarthritis, the cartilage becomes worn away. Spurs grow out from the edge of the bone, and synovial fluid increases. Altogether, the joint feels stiff and sore.

Osteoarthritis

Bone (left) and clinical (right) changes of the hand in osteoarthritis

Classification

A number of classification systems are used for gradation of osteoarthritis:

- WOMAC scale, taking into account pain, stiffness and functional limitation.

- Kellgren-Lawrence grading scale for osteoarthritis of the knee. It uses only projectional radiography features.

- Tönnis classification for osteoarthritis of the hip joint, also using only projectional radiography features.

- Knee injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (KOOS) and Hip disability and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (HOOS) surveys.

Osteoarthritis can be classified into either primary or secondary depending on whether or not there is an identifiable underlying cause.

Both primary generalized nodal osteoarthritis and erosive osteoarthritis (EOA, also called inflammatory osteoarthritis) are sub-sets of primary osteoarthritis. EOA is a much less common, and more aggressive inflammatory form of osteoarthritis which often affects the distal interphalangeal joints of the hand and has characteristic articular erosive changes on x-ray.

Osteoarthritis can be classified by the joint affected:

- Hand:

- Trapeziometacarpal osteoarthritis

- Wrist (wrist osteoarthritis)

- Vertebral column (spondylosis)

- Facet joint arthrosis

- Hip osteoarthritis

- Knee osteoarthritis

Management

Lifestyle modification (such as weight loss and exercise) and pain medications are the mainstays of treatment. Acetaminophen (also known as paracetamol) is recommended first line with NSAIDs being used as add on therapy only if pain relief is not sufficient. Medications that alter the course of the disease have not been found as of 2018. Recommendations include modification of risk factors through targeted interventions including 1) obesity and overweight, 2) physical activity, 3) dietary exposures, 4) comorbidity, 5) biomechanical factors, 6) occupational factors.

Lifestyle changes

For overweight people, weight loss may be an important factor. Patient education has been shown to be helpful in the self-management of arthritis. It decreases pain, improves function, reduces stiffness and fatigue, and reduces medical usage. Patient education can provide on average 20% more pain relief when compared to NSAIDs alone.

Physical measures

Moderate exercise may be beneficial with respect to pain and function in those with osteoarthritis of the knee and hip. These exercises should occur at least three times per week. While some evidence supports certain physical therapies, evidence for a combined program is limited. Providing clear advice, making exercises enjoyable, and reassuring people about the importance of doing exercises may lead to greater benefit and more participation. Limited evidence suggests that supervised exercise therapy may improve exercise adherence. There is not enough evidence to determine the effectiveness of massage therapy. The evidence for manual therapy is inconclusive. Functional, gait, and balance training have been recommended to address impairments of position sense, balance, and strength in individuals with lower extremity arthritis as these can contribute to a higher rate of falls in older individuals. For people with hand osteoarthritis, exercises may provide small benefits for improving hand function, reducing pain, and relieving finger joint stiffness.

Lateral wedge insoles and neutral insoles do not appear to be useful in osteoarthritis of the knee. Knee braces may help but their usefulness has also been disputed. For pain management heat can be used to relieve stiffness, and cold can relieve muscle spasms and pain. Among people with hip and knee osteoarthritis, exercise in water may reduce pain and disability, and increase quality of life in the short term. Also therapeutic exercise programs such as aerobics and walking reduce pain and improve physical functioning for up to 6 months after the end of the program for people with knee osteoarthritis.

Medication

| Treatment recommendations by risk factors | ||

|---|---|---|

| GI risk | CVD risk | Option |

| Low | Low | NSAID, or paracetamol |

| Moderate | Low | Paracetamol, or low dose NSAID with antacid |

| Low | Moderate | Paracetamol, or low dose aspirin with an antacid |

| Moderate | Moderate | Low dose paracetamol, aspirin, and antacid. Monitoring for abdominal pain or black stool. |

By mouth

The pain medication paracetamol (acetaminophen) is the first line treatment for osteoarthritis. Pain relief does not differ according to dosage. However, a 2015 review found acetaminophen to have only a small short term benefit with some laboratory concerns of liver inflammation. For mild to moderate symptoms effectiveness of acetaminophen is similar to non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) such as naproxen, though for more severe symptoms NSAIDs may be more effective. NSAIDs are associated with greater side effects such as gastrointestinal bleeding.

Another class of NSAIDs, COX-2 selective inhibitors (such as celecoxib) are equally effective when compared to nonselective NSAIDs, and have lower rates of adverse gastrointestinal effects, but higher rates of cardiovascular disease such as myocardial infarction. They are also more expensive than non-specific NSAIDs. Benefits and risks vary in individuals and need consideration when making treatment decisions, and further unbiased research comparing NSAIDS and COX-2 selective inhibitors is needed. NSAIDS applied topically are effective for a small number of people. The COX-2 selective inhibitor rofecoxib was removed from the market in 2004, as cardiovascular events were associated with long term use.

Failure to achieve desired pain relief in osteoarthritis after 2 weeks should trigger reassessment of dosage and pain medication. Opioids by mouth, including both weak opioids such as tramadol and stronger opioids, are also often prescribed. Their appropriateness is uncertain, and opioids are often recommended only when first line therapies have failed or are contraindicated. This is due to their small benefit and relatively large risk of side effects. The use of tramadol likely does not improve pain or physical function and likely increases the incidence of adverse side effects. Oral steroids are not recommended in the treatment of osteoarthritis.

Use of the antibiotic doxycycline orally for treating osteoarthritis is not associated with clinical improvements in function or joint pain. Any small benefit related to the potential for doxycycline therapy to address the narrowing of the joint space is not clear, and any benefit is outweighed by the potential harm from side effects.

Topical

There are several NSAIDs available for topical use, including diclofenac. A Cochrane review from 2016 concluded that reasonably reliable evidence is available only for use of topical diclofenac and ketoprofen in people aged over 40 years with painful knee arthritis. Transdermal opioid pain medications are not typically recommended in the treatment of osteoarthritis. The use of topical capsaicin to treat osteoarthritis is controversial, as some reviews found benefit while others did not.

Joint injections

Steroids

Joint injection of glucocorticoids (such as hydrocortisone) leads to short term pain relief that may last between a few weeks and a few months. A 2015 Cochrane review found that intra-articular corticosteroid injections of the knee did not benefit quality of life and had no effect on knee joint space; clinical effects one to six weeks after injection could not be determined clearly due to poor study quality. Another 2015 study reported negative effects of intra-articular corticosteroid injections at higher doses, and a 2017 trial showed reduction in cartilage thickness with intra-articular triamcinolone every 12 weeks for 2 years compared to placebo. A 2018 study found that intra-articular triamcinolone is associated with an increase in intraocular pressure.

Hyaluronic acid

Injections of hyaluronic acid have not produced improvement compared to placebo for knee arthritis, but did increase risk of further pain. In ankle osteoarthritis, evidence is unclear.

Platelet rich plasma

The effectiveness of injections of platelet-rich plasma is unclear; there are suggestions that such injections improve function but not pain, and are associated with increased risk. A Cochrane review of studies involving PRP found the evidence to be insufficient.

Surgery

Bone fusion

Arthrodesis (fusion) of the bones may be an option in some types of osteoarthritis. An example is ankle osteoarthritis, in which ankle fusion is considered to be the gold standard treatment in end-stage cases.

Joint replacement

If the impact of symptoms of osteoarthritis on quality of life is significant and more conservative management is ineffective, joint replacement surgery or resurfacing may be recommended. Evidence supports joint replacement for both knees and hips as it is both clinically effective and cost-effective. For people who have shoulder osteoarthritis and do not respond to medications, surgical options include a shoulder hemiarthroplasty (replacing a part of the joint), and total shoulder arthroplasty (replacing the joint).

Biological joint replacement involves replacing the diseased tissues with new ones. This can either be from the person (autograft) or from a donor (allograft). People undergoing a joint transplant (osteochondral allograft) do not need to take immunosuppressants as bone and cartilage tissues have limited immune responses. Autologous articular cartilage transfer from a non-weight-bearing area to the damaged area, called osteochondral autograft transfer system (OATS), is one possible procedure that is being studied. When the missing cartilage is a focal defect, autologous chondrocyte implantation is also an option.

Other surgical options

Osteotomy may be useful in people with knee osteoarthritis, but has not been well studied and it is unclear whether it is more effective than non-surgical treatments or other types of surgery. Arthroscopic surgery is largely not recommended, as it does not improve outcomes in knee osteoarthritis, and may result in harm. It is unclear whether surgery is beneficial in people with mild to moderate knee osteoarthritis.

Alternative medicine

Glucosamine and chondroitin

The effectiveness of glucosamine is controversial. Reviews have found it to be equal to or slightly better than placebo. A difference may exist between glucosamine sulfate and glucosamine hydrochloride, with glucosamine sulfate showing a benefit and glucosamine hydrochloride not. The evidence for glucosamine sulfate having an effect on osteoarthritis progression is somewhat unclear and if present likely modest. The Osteoarthritis Research Society International recommends that glucosamine be discontinued if no effect is observed after six months and the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence no longer recommends its use. Despite the difficulty in determining the efficacy of glucosamine, it remains a viable treatment option. The European Society for Clinical and Economic Aspects of Osteoporosis and Osteoarthritis (ESCEO) recommends glucosamine sulfate and chondroitin sulfate for knee osteoarthritis. Its use as a therapy for osteoarthritis is usually safe.

A 2015 Cochrane review of clinical trials of chondroitin found that most were of low quality, but that there was some evidence of short-term improvement in pain and few side effects; it does not appear to improve or maintain the health of affected joints.

Other remedies

Avocado–soybean unsaponifiables (ASU) is an extract made from avocado oil and soybean oil that is sold under many brand names worldwide as a dietary supplement and as a drug in France. A 2014 Cochrane review found that while ASU might help relieve pain in the short term for some people with osteoarthritis, it does not appear to improve or maintain the health of affected joints. The review noted a high-quality two-year clinical trial comparing ASU to chondroitin, which has uncertain efficacy in osteoarthritis; the study found no difference between the two. The review also found that although ASU appears to be safe, it has not been adequately studied for its safety to be determined.

A few high-quality studies of Boswellia serrata show consistent, but small, improvements in pain and function. Curcumin, phytodolor, and s-adenosyl methionine (SAMe) may be effective in improving pain. A 2009 Cochrane review recommended against the routine use of SAMe as there have not been sufficient high-quality trials performed to evaluate its effect. There is tentative evidence to support hyaluronan, methylsulfonylmethane (MSM), and rose hip.

There is little evidence supporting benefits for some supplements, including: the Ayurvedic herbal preparations with brand names Articulin F and Eazmov; Duhuo Jisheng Wan, a Chinese herbal preparation; fish liver oil; ginger; russian olive; the herbal preparation gitadyl; omega-3 fatty acids; the brand-name product Reumalax; stinging nettle; vitamins A, C, and E in combination; vitamin E alone; vitamin K; vitamin D; collagen; and willow bark. There is insufficient evidence to make a recommendation about the safety and efficacy of these treatments.

Acupuncture and other interventions

While acupuncture leads to improvements in pain relief, this improvement is small and may be of questionable importance. Waiting list–controlled trials for peripheral joint osteoarthritis do show clinically relevant benefits, but these may be due to placebo effects. Acupuncture does not seem to produce long-term benefits.

Electrostimulation techniques such as TENS have been used for twenty years to treat osteoarthritis in the knee, however there is no conclusive evidence to show that it reduces pain or disability. A Cochrane review of low-level laser therapy found unclear evidence of benefit, whereas another review found short-term pain relief for osteoarthritic knees.

Further research is needed to determine if balnotherapy for osteoarthritis (mineral baths or spa treatments) improves a person's quality of life or ability to function. The use of ice or cold packs may be beneficial; however, further research is needed. There is no evidence of benefit from placing hot packs on joints.

There is low quality evidence that therapeutic ultrasound may be beneficial for people with osteoarthritis of the knee; however, further research is needed to confirm and determine the degree and significance of this potential benefit.

There is weak evidence suggesting that electromagnetic field treatment may result in moderate pain relief; however, further research is necessary and it is not known if electromagnetic field treatment can improve quality of life or function.

Viscosupplementation for osteoarthritis of the knee may have positive effects on pain and function at 5 to 13 weeks post-injection.

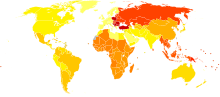

Epidemiology

| no data ≤ 200 200–220 220–240 240–260 260–280 280–300 | 300–320 320–340 340–360 360–380 380–400 ≥ 400 |

Globally, as of 2010[update], approximately 250 million people had osteoarthritis of the knee (3.6% of the population). Hip osteoarthritis affects about 0.85% of the population.

As of 2004[update], osteoarthritis globally causes moderate to severe disability in 43.4 million people. Together, knee and hip osteoarthritis had a ranking for disability globally of 11th among 291 disease conditions assessed.

As of 2012[update], osteoarthritis affected 52.5 million people in the United States, approximately 50% of whom were 65 years or older. It is estimated that 80% of the population have radiographic evidence of osteoarthritis by age 65, although only 60% of those will have symptoms. The rate of osteoarthritis in the United States is forecast to be 78 million (26%) adults by 2040.

In the United States, there were approximately 964,000 hospitalizations for osteoarthritis in 2011, a rate of 31 stays per 10,000 population. With an aggregate cost of $14.8 billion ($15,400 per stay), it was the second-most expensive condition seen in U.S. hospital stays in 2011. By payer, it was the second-most costly condition billed to Medicare and private insurance.

History

Evidence for osteoarthritis found in the fossil record is studied by paleopathologists, specialists in ancient disease and injury.

Etymology

Osteoarthritis is derived from the prefix osteo- (from Ancient Greek: ὀστέον, romanized: ostéon, lit. 'bone') combined with arthritis (from ἀρθρῖτῐς, arthrîtis, lit. ''of or in the joint''), which is itself derived from arthr- (from ἄρθρον, árthron, lit. ''joint, limb'') and -itis (from -ῖτις, -îtis, lit. ''pertaining to''), the latter suffix having come to be associated with inflammation. The -itis of osteoarthritis could be considered misleading as inflammation is not a conspicuous feature. Some clinicians refer to this condition as osteoarthrosis to signify the lack of inflammatory response, the suffix -osis (from -ωσις, -ōsis, lit. ''(abnormal) state, condition, or action'') simply referring to the pathosis itself.

Other animals

Osteoarthritis has been reported in fossils of the large carnivorous dinosaur Allosaurus fragilis.

Research

Therapies

Therapies under investigation include the following:

- Strontium ranelate - may decrease degeneration in osteoarthritis and improve outcomes

- Gene therapy - Gene transfer strategies aim to target the disease process rather than the symptoms. Cell-mediated gene therapy is also being studied. One version was approved in South Korea for the treatment of moderate knee osteoarthritis, but later revoked for the mislabeling and the false reporting of an ingredient used. The drug was administered intra-articularly.

Cause

As well as attempting to find disease-modifying agents for osteoarthritis, there is emerging evidence that a system-based approach is necessary to find the causes of osteoarthritis.

Diagnostic biomarkers

Guidelines outlining requirements for inclusion of soluble biomarkers in osteoarthritis clinical trials were published in 2015, but as of 2015[update], there are no validated biomarkers for osteoarthritis.

A 2015 systematic review of biomarkers for osteoarthritis looking for molecules that could be used for risk assessments found 37 different biochemical markers of bone and cartilage turnover in 25 publications. The strongest evidence was for urinary C-terminal telopeptide of type II collagen (uCTX-II) as a prognostic marker for knee osteoarthritis progression, and serum cartilage oligomeric matrix protein (COMP) levels as a prognostic marker for incidence of both knee and hip osteoarthritis. A review of biomarkers in hip osteoarthritis also found associations with uCTX-II. Procollagen type II C-terminal propeptide (PIICP) levels reflect type II collagen synthesis in body and within joint fluid PIICP levels can be used as a prognostic marker for early osteoarthritis.