Mccarthyism

McCarthyism is the practice of making accusations of subversion or treason, especially when related to communism, without any proper regard for evidence. The term refers to U.S. senator Joseph McCarthy (R-Wisconsin) and has its origins in the period in the United States known as the Second Red Scare, lasting from the late 1940s through the 1950s. It was characterized by heightened political repression and a campaign spreading fear of communist influence on American institutions and of espionage by Soviet agents. After the mid-1950s, McCarthyism began to decline, mainly due to the gradual loss of public popularity and opposition from the U.S. Supreme Court led by Chief Justice Earl Warren. The Warren Court made a series of rulings that helped bring an end to McCarthyism.

What would become known as the McCarthy era began before McCarthy's rise to national fame. Following the First Red Scare, President Harry S. Truman signed an executive order in 1947 to screen federal employees for association with organizations deemed "totalitarian, fascist, communist, or subversive", or advocating "to alter the form of Government of the United States by unconstitutional means." In 1949, a high-level State Department official was convicted of perjury in a case of espionage, and the Soviet Union tested an atomic bomb. The Korean War started the next year, raising tensions in the United States. In a speech in February 1950, McCarthy presented a list of alleged members of the Communist Party USA working in the State Department, which attracted press attention. McCarthyism was published for the first time in late March of that year in The Christian Science Monitor, and in a political cartoon by Herblock in The Washington Post. The term has since taken on a broader meaning, describing the excesses of similar efforts. In the early 21st century, the term is used more generally to describe reckless, unsubstantiated accusations, and demagogic attacks on the character or patriotism of political adversaries.

During the McCarthy era, hundreds of Americans were accused of being "communists" or "communist sympathizers"; they became the subject of aggressive investigations and questioning before government or private industry panels, committees, and agencies. The primary targets of such suspicions were government employees, those in the entertainment industry, academics, and labor-union activists. Suspicions were often given credence despite inconclusive or questionable evidence, and the level of threat posed by a person's real or supposed leftist associations or beliefs were sometimes exaggerated. Many people suffered loss of employment or destruction of their careers; some were imprisoned. Most of these punishments came about through trial verdicts that were later overturned, laws that were later declared unconstitutional, dismissals for reasons later declared illegal or actionable, or extra-legal procedures, such as informal blacklists, that would come into general disrepute. The most notable examples of McCarthyism include the so-called investigations conducted by Senator McCarthy, and the hearings conducted by the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC).

In his book The Bureau: The Secret History of the FBI, journalist Ronald Kessler quoted former FBI agent Robert J. Lamphere, who participated in all of the FBI's major spy cases during the McCarthy period, as saying that FBI agents who worked counterintelligence were aghast that FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover supported McCarthy. Lamphere told Kessler that "McCarthyism did all kinds of harm because he was pushing something that wasn't so." The VENONA intercepts showed that over several decades, "[t]here were a lot of spies in the government, but not all in the State Department," Lamphere said. However, "[t]he problem was that McCarthy lied about his information and figures. He made charges against people that weren't true. McCarthyism harmed the counterintelligence effort against the Soviet threat because of the revulsion it caused. All along, Hoover was helping him."

Origins

President Harry S. Truman's Executive Order 9835 of March 21, 1947, required that all federal civil-service employees be screened for "loyalty". The order said that one basis for determining disloyalty would be a finding of "membership in, affiliation with or sympathetic association" with any organization determined by the attorney general to be "totalitarian, fascist, communist or subversive" or advocating or approving the forceful denial of constitutional rights to other persons or seeking "to alter the form of Government of the United States by unconstitutional means."

The historical period that came to be known as the McCarthy era began well before Joseph McCarthy's own involvement in it. Many factors contributed to McCarthyism, some of them with roots in the First Red Scare (1917–20), inspired by communism's emergence as a recognized political force and widespread social disruption in the United States related to unionizing and anarchist activities. Owing in part to its success in organizing labor unions and its early opposition to fascism, and offering an alternative to the ills of capitalism during the Great Depression, the Communist Party of the United States increased its membership through the 1930s, reaching a peak of about 75,000 members in 1940–41. While the United States was engaged in World War II and allied with the Soviet Union, the issue of anti-communism was largely muted. With the end of World War II, the Cold War began almost immediately, as the Soviet Union installed communist puppet régimes in areas it had occupied across Central and Eastern Europe. The United States backed anti-communist forces in Greece and China.

Although the Igor Gouzenko and Elizabeth Bentley affairs had raised the issue of Soviet espionage in 1945, events in 1949 and 1950 sharply increased the sense of threat in the United States related to communism. The Soviet Union tested an atomic bomb in 1949, earlier than many analysts had expected, raising the stakes in the Cold War. That same year, Mao Zedong's communist army gained control of mainland China despite heavy American financial support of the opposing Kuomintang. Many U.S. policy people did not fully understand the situation in China, despite the efforts of China experts to explain conditions. In 1950, the Korean War began, pitting U.S., U.N., and South Korean forces against communists from North Korea and China.

During the following year, evidence of increased sophistication in Soviet Cold War espionage activities was found in the West. In January 1950, Alger Hiss, a high-level State Department official, was convicted of perjury. Hiss was in effect found guilty of espionage; the statute of limitations had run out for that crime, but he was convicted of having perjured himself when he denied that charge in earlier testimony before the HUAC. In Britain, Klaus Fuchs confessed to committing espionage on behalf of the Soviet Union while working on the Manhattan Project at Los Alamos National Laboratory during the War. Julius and Ethel Rosenberg were arrested in 1950 in the United States on charges of stealing atomic-bomb secrets for the Soviets, and were executed in 1953.

Other forces encouraged the rise of McCarthyism. The more conservative politicians in the United States had historically referred to progressive reforms, such as child labor laws and women's suffrage, as "communist" or "Red plots", trying to raise fears against such changes. They used similar terms during the 1930s and the Great Depression when opposing the New Deal policies of President Franklin D. Roosevelt. Many conservatives equated the New Deal with socialism or Communism, and thought the policies were evidence of too much influence by allegedly communist policy makers in the Roosevelt administration. In general, the vaguely defined danger of "Communist influence" was a more common theme in the rhetoric of anti-communist politicians than was espionage or any other specific activity.

McCarthy's involvement in these issues began publicly with a speech he made on Lincoln Day, February 9, 1950, to the Republican Women's Club of Wheeling, West Virginia. He brandished a piece of paper, which he claimed contained a list of known communists working for the State Department. McCarthy is usually quoted as saying: "I have here in my hand a list of 205—a list of names that were made known to the Secretary of State as being members of the Communist Party and who nevertheless are still working and shaping policy in the State Department." This speech resulted in a flood of press attention to McCarthy and helped establish his path to becoming one of the most recognized politicians in the United States.

The first recorded uses of the term "McCarthyism" were in the Christian Science Monitor on March 28, 1950 ("Their little spree with McCarthyism is no aid to consultation"); and then, on the following day, in a political cartoon by Washington Post editorial cartoonist Herbert Block (Herblock). The cartoon depicts four leading Republicans trying to push an elephant (the traditional symbol of the Republican Party) to stand on a platform atop a teetering stack of ten tar buckets, the topmost of which is labeled "McCarthyism". Block later wrote:

"nothing [was] particularly ingenious about the term, which is simply used to represent a national affliction that can hardly be described in any other way. If anyone has a prior claim on it, he's welcome to the word and to the junior senator from Wisconsin along with it. I will also throw in a set of free dishes and a case of soap."

Institutions

A number of anti-communist committees, panels, and "loyalty review boards" in federal, state, and local governments, as well as many private agencies, carried out investigations for small and large companies concerned about possible Communists in their work forces.

In Congress, the primary bodies that investigated Communist activities were the HUAC, the Senate Internal Security Subcommittee, and the Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations. Between 1949 and 1954, a total of 109 investigations were carried out by these and other committees of Congress.

On December 2, 1954, the United States Senate voted 67 to 22 to condemn McCarthy for "conduct that tends to bring the Senate into dishonor and disrepute".

Executive branch

Loyalty-security reviews

In the federal government, President Truman's Executive Order 9835 initiated a program of loyalty reviews for federal employees in 1947. It called for dismissal if there were "reasonable grounds ... for belief that the person involved is disloyal to the Government of the United States." Truman, a Democrat, was probably reacting in part to the Republican sweep in the 1946 Congressional election and felt a need to counter growing criticism from conservatives and anti-communists.

When President Dwight Eisenhower took office in 1953, he strengthened and extended Truman's loyalty review program, while decreasing the avenues of appeal available to dismissed employees. Hiram Bingham, chairman of the Civil Service Commission Loyalty Review Board, referred to the new rules he was obliged to enforce as "just not the American way of doing things." The following year, J. Robert Oppenheimer, scientific director of the Manhattan Project that built the first atomic bomb, then working as a consultant to the Atomic Energy Commission, was stripped of his security clearance after a four-week hearing. Oppenheimer had received a top-secret clearance in 1947, but was denied clearance in the harsher climate of 1954.

Similar loyalty reviews were established in many state and local government offices and some private industries across the nation. In 1958, an estimated one of every five employees in the United States was required to pass some sort of loyalty review. Once a person lost a job due to an unfavorable loyalty review, finding other employment could be very difficult. "A man is ruined everywhere and forever," in the words of the chairman of President Truman's Loyalty Review Board. "No responsible employer would be likely to take a chance in giving him a job."

The Department of Justice started keeping a list of organizations that it deemed subversive beginning in 1942. This list was first made public in 1948, when it included 78 groups. At its longest, it comprised 154 organizations, 110 of them identified as Communist. In the context of a loyalty review, membership in a listed organization was meant to raise a question, but not to be considered proof of disloyalty. One of the most common causes of suspicion was membership in the Washington Bookshop Association, a left-leaning organization that offered lectures on literature, classical music concerts, and discounts on books.

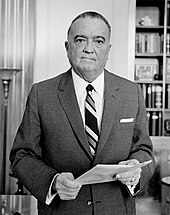

J. Edgar Hoover and the FBI

FBI director J. Edgar Hoover designed President Truman's loyalty-security program, and its background investigations of employees were carried out by FBI agents. This was a major assignment that led to the number of agents in the bureau being increased from 3,559 in 1946 to 7,029 in 1952. Hoover's sense of the communist threat and the standards of evidence applied by his bureau resulted in thousands of government workers losing their jobs. Due to Hoover's insistence upon keeping the identity of his informers secret, most subjects of loyalty-security reviews were not allowed to cross-examine or know the identities of those who accused them. In many cases, they were not even told of what they were accused.

Hoover's influence extended beyond federal government employees and beyond the loyalty-security programs. The records of loyalty review hearings and investigations were supposed to be confidential, but Hoover routinely gave evidence from them to congressional committees such as HUAC.

From 1951 to 1955, the FBI operated a secret "Responsibilities Program" that distributed anonymous documents with evidence from FBI files of communist affiliations on the part of teachers, lawyers, and others. Many people accused in these "blind memoranda" were fired without any further process.

The FBI engaged in a number of illegal practices in its pursuit of information on communists, including burglaries, opening mail, and illegal wiretaps. The members of the left-wing National Lawyers Guild were among the few attorneys who were willing to defend clients in communist-related cases, and this made the NLG a particular target of Hoover's. The office of this organization was burgled by the FBI at least 14 times between 1947 and 1951. Among other purposes, the FBI used its illegally obtained information to alert prosecuting attorneys about the planned legal strategies of NLG defense lawyers.

The FBI also used illegal undercover operations to disrupt communist and other dissident political groups. In 1956, Hoover was becoming increasingly frustrated by Supreme Court decisions that limited the Justice Department's ability to prosecute communists. At this time, he formalized a covert "dirty tricks" program under the name COINTELPRO. COINTELPRO actions included planting forged documents to create the suspicion that a key person was an FBI informer, spreading rumors through anonymous letters, leaking information to the press, calling for IRS audits, and the like. The COINTELPRO program remained in operation until 1971.

Historian Ellen Schrecker calls the FBI "the single most important component of the anti-communist crusade" and writes: "Had observers known in the 1950s what they have learned since the 1970s, when the Freedom of Information Act opened the Bureau's files, 'McCarthyism' would probably be called 'Hooverism'."

Congress

House Committee on Un-American Activities

The House Committee on Un-American Activities – commonly referred to as the HUAC – was the most prominent and active government committee involved in anti-communist investigations. Formed in 1938 and known as the Dies Committee, named for Rep. Martin Dies, who chaired it until 1944, HUAC investigated a variety of "activities", including those of German-American Nazis during World War II. The committee soon focused on Communism, beginning with an investigation into Communists in the Federal Theatre Project in 1938. A significant step for HUAC was its investigation of the charges of espionage brought against Alger Hiss in 1948. This investigation ultimately resulted in Hiss's trial and conviction for perjury, and convinced many of the usefulness of congressional committees for uncovering Communist subversion.

HUAC achieved its greatest fame and notoriety with its investigation into the Hollywood film industry. In October 1947, the Committee began to subpoena screenwriters, directors, and other movie-industry professionals to testify about their known or suspected membership in the Communist Party, association with its members, or support of its beliefs. At these testimonies, this question was asked: "Are you now or have you ever been a member of the Communist Party of the United States?" Among the first film industry witnesses subpoenaed by the committee were ten who decided not to cooperate. These men, who became known as the "Hollywood Ten", cited the First Amendment's guarantee of free speech and free assembly, which they believed legally protected them from being required to answer the committee's questions. This tactic failed, and the ten were sentenced to prison for contempt of Congress. Two of them were sentenced to six months, the rest to a year.

In the future, witnesses (in the entertainment industries and otherwise) who were determined not to cooperate with the committee would claim their Fifth Amendment protection against self-incrimination. William Grooper and Rockwell Kent, the only two visual artists to be questioned by McCarthy, both took this approach, and emerged relatively unscathed by the experience. However, while this usually protected witnesses from a contempt-of-Congress citation, it was considered grounds for dismissal by many government and private-industry employers. The legal requirements for Fifth Amendment protection were such that a person could not testify about his own association with the Communist Party and then refuse to "name names" of colleagues with communist affiliations. Thus, many faced a choice between "crawl[ing] through the mud to be an informer," as actor Larry Parks put it, or becoming known as a "Fifth Amendment Communist"—an epithet often used by Senator McCarthy.

Senate committees

In the Senate, the primary committee for investigating communists was the Senate Internal Security Subcommittee (SISS), formed in 1950 and charged with ensuring the enforcement of laws relating to "espionage, sabotage, and the protection of the internal security of the United States." The SISS was headed by Democrat Pat McCarran and gained a reputation for careful and extensive investigations. This committee spent a year investigating Owen Lattimore and other members of the Institute of Pacific Relations. As had been done numerous times before, the collection of scholars and diplomats associated with Lattimore (the so-called China Hands) were accused of "losing China", and while some evidence of pro-communist attitudes was found, nothing supported McCarran's accusation that Lattimore was "a conscious and articulate instrument of the Soviet conspiracy". Lattimore was charged with perjuring himself before the SISS in 1952. After many of the charges were rejected by a federal judge and one of the witnesses confessed to perjury, the case was dropped in 1955.

McCarthy headed the Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations in 1953 and 1954, and during that time, used it for a number of his communist-hunting investigations. McCarthy first examined allegations of communist influence in the Voice of America, and then turned to the overseas library program of the State Department. Card catalogs of these libraries were searched for works by authors McCarthy deemed inappropriate. McCarthy then recited the list of supposedly pro-communist authors before his subcommittee and the press. Yielding to the pressure, the State Department ordered its overseas librarians to remove from their shelves "material by any controversial persons, Communists, fellow travelers, etc." Some libraries actually burned the newly forbidden books. Though he did not block the State Department from carrying out this order, President Eisenhower publicly criticized the initiative as well, telling the graduating class of Dartmouth College President in 1953: “Don’t join the book burners! … Don’t be afraid to go to the library and read every book so long as that document does not offend our own ideas of decency—that should be the only censorship.” The President then settled for a compromise by retaining the ban on Communist books written by Communists, while also allowing the libraries to keep books on Communism written by anti-Communists.

McCarthy's committee then began an investigation into the United States Army. This began at the Army Signal Corps laboratory at Fort Monmouth. McCarthy garnered some headlines with stories of a dangerous spy ring among the Army researchers, but ultimately nothing came of this investigation.

McCarthy next turned his attention to the case of a U.S. Army dentist who had been promoted to the rank of major despite having refused to answer questions on an Army loyalty review form. McCarthy's handling of this investigation, including a series of insults directed at a brigadier general, led to the Army–McCarthy hearings, with the Army and McCarthy trading charges and counter-charges for 36 days before a nationwide television audience. While the official outcome of the hearings was inconclusive, this exposure of McCarthy to the American public resulted in a sharp decline in his popularity. In less than a year, McCarthy was censured by the Senate, and his position as a prominent force in anti-communism was essentially ended.

Blacklists

On November 25, 1947, the day after the House of Representatives approved citations of contempt for the Hollywood Ten, Eric Johnston, president of the Motion Picture Association of America, issued a press release on behalf of the heads of the major studios that came to be referred to as the Waldorf Statement. This statement announced the firing of the Hollywood Ten and stated: "We will not knowingly employ a Communist or a member of any party or group which advocates the overthrow of the government of the United States..." This marked the beginning of the Hollywood blacklist. In spite of the fact that hundreds would be denied employment, the studios, producers, and other employers did not publicly admit that a blacklist existed.

At this time, private loyalty-review boards and anti-communist investigators began to appear to fill a growing demand among certain industries to certify that their employees were above reproach. Companies that were concerned about the sensitivity of their business, or which, like the entertainment industry, felt particularly vulnerable to public opinion made use of these private services. For a fee, these teams would investigate employees and question them about their politics and affiliations.

At such hearings, the subject would usually not have a right to the presence of an attorney, and as with HUAC, the interviewee might be asked to defend himself against accusations without being allowed to cross-examine the accuser. These agencies would keep cross-referenced lists of leftist organizations, publications, rallies, charities, and the like, as well as lists of individuals who were known or suspected communists. Books such as Red Channels and newsletters such as Counterattack and Confidential Information were published to keep track of communist and leftist organizations and individuals. Insofar as the various blacklists of McCarthyism were actual physical lists, they were created and maintained by these private organizations.

Laws and arrests

Efforts to protect the United States from the perceived threat of communist subversion were particularly enabled by several federal laws. The Alien Registration Act or Smith Act of 1940 made the act of "knowingly or willfully advocate, abet, advise or teach the ... desirability or propriety of overthrowing the Government of the United States or of any State by force or violence, or for anyone to organize any association which teaches, advises or encourages such an overthrow, or for anyone to become a member of or to affiliate with any such association" a criminal offense.

Hundreds of communists and others were prosecuted under this law between 1941 and 1957. Eleven leaders of the Communist Party were convicted under the Smith Act in 1949 in the Foley Square trial. Ten defendants were given sentences of five years and the eleventh was sentenced to three years. The defense attorneys were cited for contempt of court and given prison sentences. In 1951, 23 other leaders of the party were indicted, including Elizabeth Gurley Flynn, a founding member of the American Civil Liberties Union. Many were convicted on the basis of testimony that was later admitted to be false. By 1957, 140 leaders and members of the Communist Party had been charged under the law, of whom 93 were convicted.

The McCarran Internal Security Act, which became law in 1950, has been described by scholar Ellen Schrecker as "the McCarthy era's only important piece of legislation" (the Smith Act technically antedated McCarthyism). However, the McCarran Act had no real effect beyond legal harassment. It required the registration of Communist organizations with the U.S. Attorney General and established the Subversive Activities Control Board to investigate possible communist-action and communist-front organizations so they could be required to register. Due to numerous hearings, delays, and appeals, the act was never enforced, even with regard to the Communist Party of the United States itself, and the major provisions of the act were found to be unconstitutional in 1965 and 1967. In 1952, the Immigration and Nationality, or McCarran–Walter, Act was passed. This law allowed the government to deport immigrants or naturalized citizens engaged in subversive activities and also to bar suspected subversives from entering the country.

The Communist Control Act of 1954 was passed with overwhelming support in both houses of Congress after very little debate. Jointly drafted by Republican John Marshall Butler and Democrat Hubert Humphrey, the law was an extension of the Internal Security Act of 1950, and sought to outlaw the Communist Party by declaring that the party, as well as "Communist-Infiltrated Organizations" were "not entitled to any of the rights, privileges, and immunities attendant upon legal bodies." While the Communist Control Act had an odd mix of liberals and conservatives among its supporters, it never had any significant effect.

The act was successfully applied only twice. In 1954 it was used to prevent Communist Party members from appearing on the New Jersey state ballot, and in 1960, it was cited to deny the CPUSA recognition as an employer under New York state's unemployment compensation system. The New York Post called the act "a monstrosity", "a wretched repudiation of democratic principles," while The Nation accused Democratic liberals of a "neurotic, election-year anxiety to escape the charge of being 'soft on Communism' even at the expense of sacrificing constitutional rights."

Repression in the individual states

In addition to the federal laws and responding to the worries of the local opinion, several states enacted anti-communist statutes.

By 1952, several states had enacted statutes against criminal anarchy, criminal syndicalism, and sedition; banned from public employment or even from receiving public aid, communists and "subversives"; asked for loyalty oaths from public servants, and severely restricted or even banned the Communist Party. In addition, six states had equivalents to the HUAC. The California Senate Factfinding Subcommittee on Un-American Activities and the Florida Legislative Investigation Committee were established by their respective legislatures.

Some of these states had very severe, or even extreme, laws against communism. In 1950, Michigan enacted life imprisonment for subversive propaganda; the following year, Tennessee enacted death penalty for advocating the violent overthrow of the government. Death penalty for membership of the Communist Party was discussed in Texas by Governor Allan Shivers, who described it as "worse than murder."

Municipalities and counties also enacted anti-communist ordinances: Los Angeles banned any communist or "Muscovite model of police-state dictatorship" from owning any arm and Birmingham, Alabama, and Jacksonville, Florida, banned any communist from being within the city's limits.

Popular support

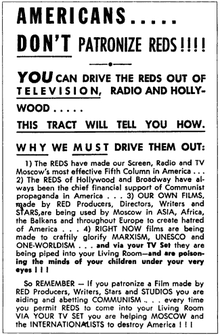

McCarthyism was supported by a variety of groups, including the American Legion and various other anti-communist organizations. One core element of support was a variety of militantly anti-communist women's groups such as the American Public Relations Forum and the Minute Women of the U.S.A.. These organized tens of thousands of housewives into study groups, letter-writing networks, and patriotic clubs that coordinated efforts to identify and eradicate what they saw as subversion.

Although far-right radicals were the bedrock of support for McCarthyism, they were not alone. A broad "coalition of the aggrieved" found McCarthyism attractive, or at least politically useful. Common themes uniting the coalition were opposition to internationalism, particularly the United Nations; opposition to social welfare provisions, particularly the various programs established by the New Deal; and opposition to efforts to reduce inequalities in the social structure of the United States.

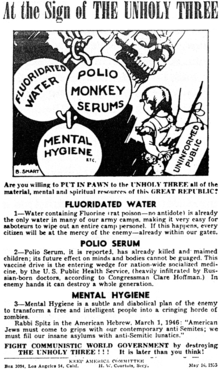

One focus of popular McCarthyism concerned the provision of public health services, particularly vaccination, mental health care services, and fluoridation, all of which were denounced by some to be communist plots to poison or brainwash the American people. Such viewpoints led to collisions between McCarthyite radicals and supporters of public-health programs, most notably in the case of the Alaska Mental Health Bill controversy of 1956.

William F. Buckley Jr., the founder of the influential conservative political magazine National Review, wrote a defense of McCarthy, McCarthy and his Enemies, in which he asserted that "McCarthyism ... is a movement around which men of good will and stern morality can close ranks."

In addition, as Richard Rovere points out, many ordinary Americans became convinced that there must be "no smoke without fire" and lent their support to McCarthyism. The Gallup poll found that at his peak in January 1954, 50% of the American public supported McCarthy, while 29% had an unfavorable opinion. His support fell to 34% in June 1954. Republicans tended to like what McCarthy was doing and Democrats did not, though McCarthy had significant support from traditional Democratic ethnic groups, especially Catholics, as well as many unskilled workers and small-business owners. (McCarthy himself was a Catholic.) He had very little support among union activists and Jews.

Portrayals of Communists

Those who sought to justify McCarthyism did so largely through their characterization of communism, and American communists in particular. Proponents of McCarthyism claimed that the CPUSA was so completely under Moscow's control that any American communist was a puppet of the Soviet intelligence services. This view is supported by recent documentation from the archives of the KGB as well as post-war decodes of wartime Soviet radio traffic from the Venona Project, showing that Moscow provided financial support to the CPUSA and had significant influence on CPUSA policies. J. Edgar Hoover commented in a 1950 speech, "Communist members, body and soul, are the property of the Party."

This attitude was not confined to arch-conservatives. In 1940, the American Civil Liberties Union ejected founding member Elizabeth Gurley Flynn, saying that her membership in the Communist Party was enough to disqualify her as a civil libertarian. In the government's prosecutions of Communist Party members under the Smith Act (see above), the prosecution case was based not on specific actions or statements by the defendants, but on the premise that a commitment to violent overthrow of the government was inherent in the doctrines of Marxism–Leninism. Passages of the CPUSA constitution that specifically rejected revolutionary violence were dismissed as deliberate deception.

In addition, it was often claimed that the party didn't allow members to resign; thus someone who had been a member for a short time decades previously could be thought a current member. Many of the hearings and trials of McCarthyism featured testimony by former Communist Party members such as Elizabeth Bentley, Louis Budenz, and Whittaker Chambers, speaking as expert witnesses.

Various historians and pundits have discussed alleged Soviet-directed infiltration of the U.S. government and the possible collaboration of high U.S. government officials.

Victims of McCarthyism

Estimating the number of victims of McCarthy is difficult. The number imprisoned is in the hundreds, and some ten or twelve thousand lost their jobs. In many cases, simply being subpoenaed by HUAC or one of the other committees was sufficient cause to be fired.

For the vast majority, though, both the potential for them to do harm to the nation and the nature of their communist affiliation were tenuous. After the extremely damaging "Cambridge Five" spy scandal (Guy Burgess, Donald Maclean, Kim Philby, Anthony Blunt, et al.), suspected homosexuality was also a common cause for being targeted by McCarthyism. The hunt for "sexual perverts", who were presumed to be subversive by nature, resulted in over 5,000 federal workers being fired, and thousands were harassed and denied employment. Many have termed this aspect of McCarthyism the "lavender scare".

Homosexuality was classified as a psychiatric disorder in the 1950s. However, in the context of the highly politicized Cold War environment, homosexuality became framed as a dangerous, contagious social disease that posed a potential threat to state security. As the family was believed to be the cornerstone of American strength and integrity, the description of homosexuals as "sexual perverts" meant that they were both unable to function within a family unit and presented the potential to poison the social body. This era also witnessed the establishment of widely spread FBI surveillance intended to identify homosexual government employees.

The McCarthy hearings and according "sexual pervert" investigations can be seen to have been driven by a desire to identify individuals whose ability to function as loyal citizens had been compromised. McCarthy began his campaign by drawing upon the ways in which he embodied traditional American values to become the self-appointed vanguard of social morality.

In the film industry, more than 300 actors, authors, and directors were denied work in the U.S. through the unofficial Hollywood blacklist. Blacklists were at work throughout the entertainment industry, in universities and schools at all levels, in the legal profession, and in many other fields. A port-security program initiated by the Coast Guard shortly after the start of the Korean War required a review of every maritime worker who loaded or worked aboard any American ship, regardless of cargo or destination. As with other loyalty-security reviews of McCarthyism, the identities of any accusers and even the nature of any accusations were typically kept secret from the accused. Nearly 3,000 seamen and longshoremen lost their jobs due to this program alone.

Some of the notable people who were blacklisted or suffered some other persecution during McCarthyism include:

- Larry Adler, musician

- Nelson Algren, writer

- Lucille Ball, actress, model, and film studio executive.

- Alvah Bessie, Abraham Lincoln Brigade, writer, journalist, screenwriter, Hollywood Ten

- Elmer Bernstein, composer and conductor

- Leonard Bernstein, conductor, pianist, composer

- David Bohm, physicist and philosopher

- Bertolt Brecht, poet, playwright, screenwriter

- Archie Brown, Abraham Lincoln Brigade, WW II vet, union leader, imprisoned. Successfully challenged Landrum–Griffin Act provision

- Esther Brunauer, forced from the U.S. State Department

- Luis Buñuel, film director, producer

- Charlie Chaplin, actor and director

- Aaron Copland, composer

- Bartley Crum, attorney

- Howard Da Silva, actor

- Jules Dassin, director

- Dolores del Río, actress

- Edward Dmytryk, director, Hollywood Ten

- W.E.B. Du Bois, civil rights activist and author

- George A. Eddy, pre-Keynesian Harvard economist, US Treasury monetary policy specialist

- Albert Einstein, Nobel Prize-winning physicist, philosopher, mathematician, activist

- Hanns Eisler, composer

- Howard Fast, writer

- Lion Feuchtwanger, novelist and playwright

- Carl Foreman, writer of High Noon

- John Garfield, actor

- C.H. Garrigues, journalist

- Jack Gilford, actor

- Allen Ginsberg, Beat poet

- Ruth Gordon, actress

- Lee Grant, actress

- Dashiell Hammett, author

- Elizabeth Hawes, clothing designer, author, equal rights activist

- Lillian Hellman, playwright

- Dorothy Healey, union organizer, CPUSA official

- Lena Horne, singer

- Langston Hughes, writer, poet, playwright

- Marsha Hunt, actress

- Sam Jaffe, actor

- Theodore Kaghan, diplomat

- Garson Kanin, writer and director

- Danny Kaye, comedian, singer

- Benjamin Keen, historian

- Otto Klemperer, conductor and composer

- Gypsy Rose Lee, actress and stripper

- Cornelius Lanczos, mathematician and physicist

- Ring Lardner Jr., screenwriter, Hollywood Ten

- Arthur Laurents, playwright

- Philip Loeb, actor

- Joseph Losey, director

- Albert Maltz, screenwriter, Hollywood Ten

- Heinrich Mann, novelist

- Klaus Mann, writer

- Thomas Mann, Nobel Prize winning novelist and essayist

- Thomas McGrath, poet

- Burgess Meredith, actor

- Arthur Miller, playwright and essayist

- Jessica Mitford, author, muckraker. Refused to testify to HUAC.

- Dimitri Mitropoulos, conductor, pianist, composer

- Zero Mostel, actor

- Joseph Needham, biochemist, sinologist, historian of science

- J. Robert Oppenheimer, physicist, scientific director of the Manhattan Project

- Dorothy Parker, writer, humorist

- Linus Pauling, chemist, Nobel prizes for Chemistry and Peace

- Samuel Reber, diplomat

- Al Richmond, union organizer, editor

- Martin Ritt, actor and director

- Paul Robeson, actor, athlete, singer, writer, political activist

- Edward G. Robinson, actor

- Waldo Salt, screenwriter

- Jean Seberg, actress

- Pete Seeger, folk singer, songwriter

- Artie Shaw, jazz musician, bandleader, author

- Irwin Shaw, writer

- William L. Shirer, journalist, author

- Lionel Stander, actor

- Dirk Jan Struik, mathematician, historian of maths

- Paul Sweezy, economist and founder-editor of Monthly Review

- Charles W. Thayer, diplomat

- Dalton Trumbo screenwriter, Hollywood Ten

- Tsien Hsue-shen, physicist

- Sam Wanamaker, actor, director, responsible for recreating Shakespeare's Globe Theatre in London, England.

- Orson Welles, actor, author, film director

- Gene Weltfish, anthropologist fired from Columbia University

In 1953, Robert K. Murray, a young professor of history at Pennsylvania State University who had served as an intelligence officer in World War II, was revising his dissertation on the Red Scare of 1919–20 for publication until Little, Brown and Company decided that "under the circumstances ... it wasn't wise for them to bring this book out." He learned that investigators were questioning his colleagues and relatives. The University of Minnesota press published his volume, Red Scare: A Study in National Hysteria, 1919–1920, in 1955.

Critical reactions

The nation was by no means united behind the policies and activities that have come to be associated with McCarthyism. The many critics of various aspects of McCarthyism included many figures not generally noted for their liberalism.

For example, in his overridden veto of the McCarran Internal Security Act of 1950, President Truman wrote, "In a free country, we punish men for the crimes they commit, but never for the opinions they have." Truman also unsuccessfully vetoed the Taft–Hartley Act, which among other provisions denied trade unions National Labor Relations Board protection unless union leaders signed affidavits swearing they were not and had never been Communists. In 1953, after he left office, Truman criticized the current Eisenhower administration:

It is now evident that the present Administration has fully embraced, for political advantage, McCarthyism. I am not referring to the Senator from Wisconsin. He is only important in that his name has taken on the dictionary meaning of the word. It is the corruption of truth, the abandonment of the due process law. It is the use of the big lie and the unfounded accusation against any citizen in the name of Americanism or security. It is the rise to power of the demagogue who lives on untruth; it is the spreading of fear and the destruction of faith in every level of society.

On June 1, 1950, Senator Margaret Chase Smith, a Maine Republican, delivered a speech to the Senate she called a "Declaration of Conscience". In a clear attack upon McCarthyism, she called for an end to "character assassinations" and named "some of the basic principles of Americanism: The right to criticize; The right to hold unpopular beliefs; The right to protest; The right of independent thought". She said "freedom of speech is not what it used to be in America", and decried "cancerous tentacles of 'know nothing, suspect everything' attitudes". Six other Republican senators—Wayne Morse, Irving M. Ives, Charles W. Tobey, Edward John Thye, George Aiken, and Robert C. Hendrickson—joined Smith in condemning the tactics of McCarthyism.

Elmer Davis, one of the most highly respected news reporters and commentators of the 1940s and 1950s, often spoke out against what he saw as the excesses of McCarthyism. On one occasion he warned that many local anti-communist movements constituted a "general attack not only on schools and colleges and libraries, on teachers and textbooks, but on all people who think and write ... in short, on the freedom of the mind".

In 1952, the Supreme Court upheld a lower-court decision