Centralopathic Epilepsy

Description

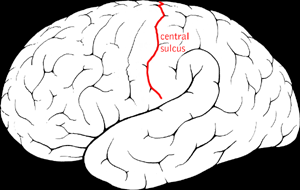

Benign epilepsy of childhood with centrotemporal spikes (BECTS) or sharp waves, also known as rolandic epilepsy, is the most common idiopathic childhood epilepsy syndrome (Neubauer et al., 1998). It is termed 'rolandic' epilepsy because of the characteristic features of partial seizures involving the region around the lower portion of the central gyrus of Rolando. This results in classic focal seizures that affect the vocal tract, beginning with guttural sounds at the larynx and sensorimotor symptoms that progress to the tongue, mouth, and face, resulting in hypersalivation and speech arrest. Seizures most often occur in sleep shortly before awakening. The disorder occurs more often in boys than in girls (3:2). Rolandic epilepsy is considered a neurodevelopmental disorder, affecting 0.2% of the population. Affected individuals may have learning disabilities or behavioral problems; however, the seizures and accompanying problems usually remit during adolescence (summary by Strug et al., 2009).

See also focal epilepsy and speech disorder (FESD; 245570), which is caused by mutation in the GRIN2A gene (138253) on chromosome 16p13. Some patients with GRIN2A mutations show features consistent with a clinical diagnosis of BECTS. Some patients with DEPDC5 (614191) mutations may show features consistent with rolandic epilepsy (see FFEVF, 604364).

Clinical FeaturesBenign centrotemporal epilepsy has a mean age of onset of 10 years and includes brief, hemifacial partial seizures that tend to become generalized, often at night. The EEG findings include slow, diphasic, high voltage, centrotemporal spikes, activated by sleep. The prognosis is excellent; recovery is the rule. Metrakos and Metrakos (1961) concluded that the centrencephalic type of electroencephalogram (associated with 'centralopathic epilepsy') is an expression of an autosomal dominant gene, with the unusual characteristics of a very low penetrance at birth, a rapid rise to nearly complete penetrance for ages 4.5 to 16.5 years, and a gradual decline to almost no penetrance after the age of 40.5 years. In this form of epilepsy, seizures of varying clinical appearance are associated with paroxysmal, diffuse, bilateral synchronous spike-wave EEG abnormalities. Although their studies did not lead them to a definite dominant hypothesis, Bray and Wiser (1964, 1965) presented evidence for a genetic basis for a 'temporal-central focal epilepsy.'

InheritanceHeijbel et al. (1975) studied 19 probands. Of 34 sibs, 15% had seizures and rolandic discharges and 19% had rolandic discharges in isolation. Of the 38 parents, 11% had a history of seizures in childhood and 3% had rolandic discharges on EEG. Heijbel et al. (1975) concluded that an autosomal dominant gene with age-dependent penetrance is responsible for the EEG trait.

In a study of 8 twin pairs, 6 monozygotic (MZ) and 2 dizygotic (DZ), in which 1 twin had benign rolandic epilepsy, Vadlamudi et al. (2004) found no concordance for the disease in any of the twin pairs. Age at onset in the affected probands ranged from 5 to 10 years, and was characterized by partial seizures with secondary generalization, often at night. EEG studies showed unilateral centrotemporal spikes; all EEG studies in the unaffected twins were normal. Vadlamudi et al. (2004) concluded that benign rolandic epilepsy does not have a strong genetic component and suggested that earlier studies were not accurate in indicating autosomal dominant inheritance of the disorder.

MappingBy genomewide analysis of 38 families ascertained by a proband with rolandic epilepsy, Strug et al. (2009) found linkage to a region on chromosome 11p13 (highest multipoint lod score of 4.30 at D11S914 under a dominant mode of inheritance with 50% penetrance). The candidate region spans from 43.17 to 56.88 cM. Candidate SNP analysis across the linkage region in 68 cases and 187 controls, including those from the linkage study, identified significant associations with 3 SNPs, rs964112 in intron 9, rs11031434 in intron 6, and rs986527 in intron 5 of the ELP4 gene (606985) (p values from 0.001 to 0.0008; OR, 1.80 to 2.04). Analysis of a replication sample of 40 cases and 120 controls from Canada yielded a significant association with all 3 SNPs and an additional SNP rs2104246. Pure likelihood joint analysis of the discovery and replication samples yielded a likelihood ratio (LR) of 629:1 for rs986527 (p = 0.0002; OR, 1.88) and LR of 590:1 for rs964112 (p = 0.0002; OR, 1.88). The significant SNPs are in linkage disequilibrium with each other. Sequencing of coding regions of the ELP4 gene did not identify pathogenic mutations.

Reinthaler et al. (2014) did not find an association between variation in the coding region of the ELP4 gene and rolandic epilepsy among 204 patients. The frequency of rare variants found in patients did not differ from the Exome Variant Server database. Further studies of 280 patients and 196 controls did not find a disease association with 3 intronic SNPs identified by Strug et al. (2009), with an expanded SNP association analysis covering the whole ELP4 gene, or with structural variations covering the genomic region of ELP4 or any of 11 other interacting genes.

Genetic Heterogeneity

In 22 nuclear families with BECTS, Neubauer et al. (1998) found evidence of linkage to chromosome 15q14. Multipoint nonparametric linkage analysis yielded a nominal p value of 0.000494. Best parametric results were obtained under an autosomal recessive model with heterogeneity (multipoint lod score 3.56 with 70% of families linked to the locus). These markers were localized close to the CHRNA7 gene (118511). The authors noted that juvenile myoclonic epilepsy (EJM2; 604827), a form of idiopathic generalized epilepsy, had been mapped to the same region. Strug et al. (2009) noted that the 15q14 locus had not been replicated previously and that their study did not find linkage at chromosome 15q14.