Gitelman Syndrome

A rare syndrome characterized by hypokalemic metabolic alkalosis in combination with significant hypomagnesemia and low urinary calcium excretion.

Epidemiology

Gitelman syndrome (GS) prevalence is estimated at 1 to 10 per 40,000 and potentially higher in Asia. GS is arguably the most frequent inherited tubulopathy.

Clinical description

GS presents mainly in adolescents and adults but also encountered in children, as early as in the neonatal period. The diagnosis may be incidental, due to blood tests obtained for unrelated reasons. Clinical symptoms may include salt craving, thirst and nocturia, transient periods of muscle weakness and tetany, sometimes accompanied by abdominal pain. Paresthesias, especially in the face, may occur. Remarkably, some patients are completely asymptomatic. In adulthood, chondrocalcinosis may appear, which can be associated with inflammation over the affected joints. Blood pressure is typically lower than that in the general population, although reports of hypertension in adult patients exist. Sudden cardiac arrest has been described in case reports and long QT syndrome may be present. In general, growth is normal but can be delayed.

Etiology

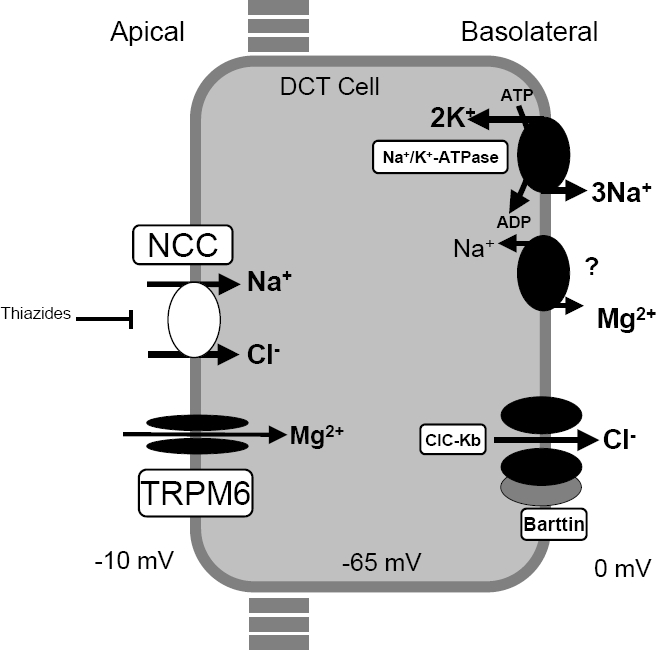

GS is caused by biallelic inactivating mutations in the SLC12A3 gene encoding the thiazide-sensitive sodium-chloride cotransporter NCC expressed in the apical membrane of cells lining the distal convoluted tubule. At present, more than 350 different NCC mutations throughout the whole protein have been identified.

Diagnostic methods

Diagnosis is based on the clinical symptoms and biochemical abnormalities (chronic hypokalemia, metabolic alkalosis, hypomagnesemia and hypocalciuria) and can be confirmed by genetic testing.

Differential diagnosis

Bartter syndrome (especially type III, caused by mutation in CLCNKB) can be clinically indistinguishable from GS. Mutation in the HNF1B can mimic the electrolyte abnormalities (particularly hypomagnesemia) encountered in GS. Biochemical abnormalities are identical in EAST/SESAME syndrome, but the extra renal features allow it to be distinguished from GS. Chronic thiazide use can cause an acquired GS-like clinical picture.

Antenatal diagnosis

Antenatal diagnosis for GS is technically feasible but not advised because of the good prognosis in the majority of patients.

Genetic counseling

Genetic counseling should be offered to at-risk couples (both individuals are carriers of a disease-causing mutation) informing them that there is a 25% risk of having an affected child at each pregnancy.

Management and treatment

The management of GS should be individualized and at least annual follow-up in a nephrology clinic to monitor potential complications and evolution is advocated. It is recommended to encourage patients to follow their propensity for salt consumption. Lifelong supplementation of salt, potassium (KCl) or magnesium supplementation (magnesium-oxide and magnesium-sulfate) should be considered. Many symptoms are improved by supplementation, but there is no evidence correlating the severity of biochemical abnormalities with the severity of symptoms. Cardiac work-up should be offered to screen for risk factors for cardiac arrhythmias. All GS patients are encouraged to maintain a high sodium and high potassium diet.

Prognosis

To date, there is no evidence that GS affects life expectancy.