Frontotemporal Dementia, Chromosome 3-Linked

A number sign (#) is used with this entry because of evidence that frontotemporal dementia mapping to chromosome 3 is caused by heterozygous mutation in the CHMP2B gene (609512) on chromosome 3p11.

Mutation in the CHMP2B gene can also cause a form of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS17; 614696).

DescriptionA substantial minority of degenerative dementias, perhaps 10%, lack the distinctive pathologic features that allow subclassification as Alzheimer disease (see 104300) or other forms of dementia. In perhaps half of these cases of nonspecific dementia, there is a positive family history of dementia, with an apparent autosomal dominant mode of inheritance.

See also frontotemporal lobe dementia (FLDEM; 600274), which maps to chromosome 17 and is caused by mutation in the microtubule-associated protein tau gene (MAPT; 157140).

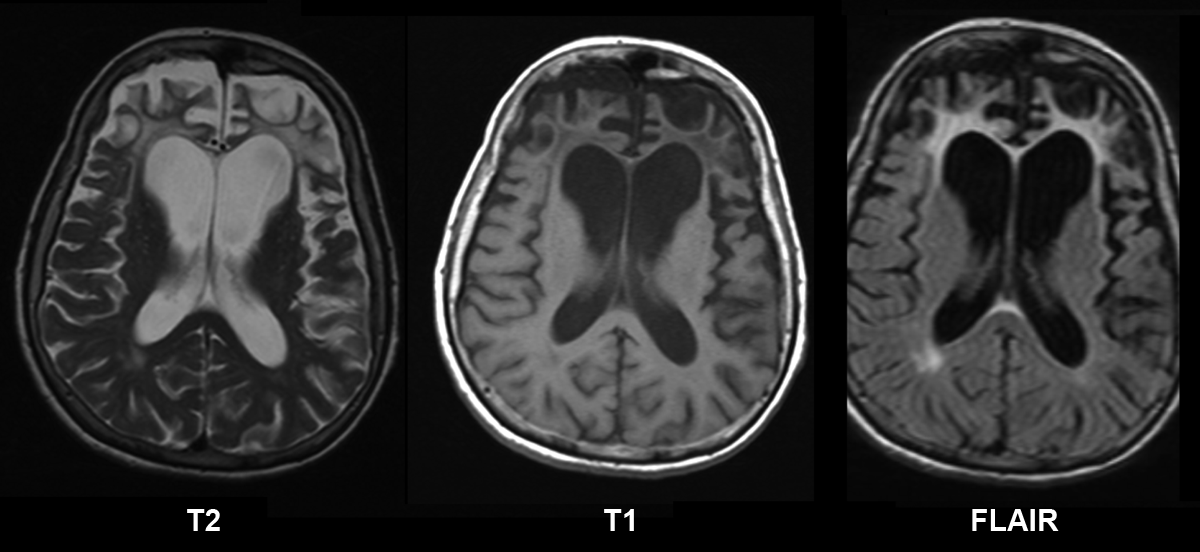

Clinical FeaturesBrown et al. (1995) studied a large kindred from the Jutland region of Denmark, constituting the largest published pedigree with multiple members affected by dementia unassociated with distinctive histopathologic features. The family had previously been described by Gydesen et al. (1987). Gydesen et al. (2002) provided additional clinical information on 22 affected individuals spanning 3 generations of this Danish kindred. The disease presented at an average age of 57 years with an insidious change in personality and behavior, including memory loss, cognitive decline, apathy, aggressiveness, stereotyped behavior, and disinhibition. Later in the illness, most patients developed a motor syndrome with abnormal gait, rigidity, hyperreflexia, and pyramidal signs. PET scan of 2 affected individuals revealed a global reduction in cerebral blood flow, and pathologic examination of several individuals showed generalized cerebral atrophy most prominent in the frontal and parietal lobes. Microscopic examination revealed cortical neuronal loss, astrocytosis, and white matter changes due to loss of myelin, but no plaques, fibrillary tangles, or inclusions. The authors termed the disorder FTD3 (chromosome 3-linked frontotemporal dementia). Gydesen et al. (2002) noted that the family reported by Kim et al. (1981) showed similarities to FTD3.

Poduslo et al. (1999) described a patient with a family history of dementia who presented with the clinical signs of Alzheimer disease which lasted for 13 years. At autopsy, brain tissue had amyloid-containing neuritic plaques, but no fibrillary tangles (i.e., the tissue was negative for staining with tau antibody). Furthermore, genetic analysis of DNA from family members revealed no linkage with chromosome 17 markers, where another form of frontotemporal dementia (FLDEM; 600274) had been mapped. Linkage was found with chromosome 3 markers, located, however, somewhat 'downstream' from those linked in the Danish family reported by Brown et al. (1995) and Brown (1998) (see MAPPING). Poduslo et al. (1999) may thus have described a distinct entity; see 604154.

Van der Zee et al. (2008) reported a Belgian woman with onset of frontotemporal dementia at age 58 years. Initial symptoms included progressive dysgraphia, memory loss, and mild disinhibition. Two years later, she had a light disorientation in space and time, severe dysgraphia, confabulation, dyspraxia, and dyscalculia. Brain CT scan showed mild frontal cortical atrophy. At the age of 64, she was clearly disoriented in space and time, her handwriting had become unreadable, and she was dyslexic with logorrhoea and perseveration. Repeat CT scan showed generalized cortical atrophy. Her mother and maternal aunt were reportedly similarly affected.

InheritanceGydesen et al. (2002) noted that the transmission pattern of dementia in a large affected Danish family was consistent with autosomal dominant inheritance.

MappingIn a large Danish kindred segregating dementia, Brown et al. (1995) mapped the disease locus to a 12-cM region of chromosome 3 spanning the centromere. Haplotype analysis demonstrated a region between markers D3S1284 and D3S1603 that was shared by all affected individuals. The disease appeared to present at an earlier age when paternally inherited. On gathering more information from affected individuals in this family, however, Gydesen et al. (2002) found that evidence for paternal anticipation had been weakened.

PathogenesisUrwin et al. (2010) described endosomal pathology in CHMP2B mutation-positive patient brains and also identified and characterized abnormal endosomes in patient fibroblasts. Functional studies demonstrated a specific disruption of endosome-lysosome fusion but not protein sorting by the multivesicular body (MVB). The authors proposed a mechanism for impaired endosome-lysosome fusion whereby mutant CHMP2B constitutively binds to MVBs and prevents recruitment of proteins, such as Rab7 (602298), that are necessary for fusion to occur.

Molecular GeneticsIn 11 affected members of a large Danish family with frontotemporal dementia reported by Brown et al. (1995) and Gydesen et al. (2002), Skibinski et al. (2005) identified a heterozygous mutation in the CHMPB2 gene (609512.0001). The authors identified a different CHMPB2 mutation (609512.0002) in a single unrelated patient with nonspecific dementia.

Momeni et al. (2006) did not identify pathogenic mutations in the CHMPB2 gene in 128 probands with frontotemporal dementia in whom MAPT mutations had been excluded. A truncating mutation in the CHMPB2 gene was identified in 2 middle-aged unaffected Afrikaner individuals from a large affected family; however, their affected father and 5 affected paternal relatives did not have the mutation. The maternal side of the family had no reported dementia. Momeni et al. (2006) noted that the large Danish family reported by Skibinski et al. (2005) had a similar truncating mutation in the CHMPB2 gene, which resulted from a different nucleotide change. The findings raised questions about the pathogenicity of the CHMPB2 mutation identified by Skibinski et al. (2005) and suggested that CHMPB2 mutations are not a common cause of frontotemporal dementia.

Cannon et al. (2006) did not identify pathogenic CHMPB2 mutations in 141 familial frontotemporal probands from the U.S. and U.K. In addition, the splice site mutation reported by Skibinski et al. (2005) was not found in 450 control individuals.

Van der Zee et al. (2008) identified a truncating mutation in the CHMPB2 gene (609512.0004) in a Belgian patient with autosomal dominant frontotemporal lobar degeneration.

NomenclatureMacKenzie et al. (2010) suggested that the neuropathologic term 'FTLD-UPS' be used for CHMPB2-related FTLD, because the inclusions are only detectable with immunohistochemistry against proteins of the ubiquitin proteasome system (UPS).