Multiple Sclerosis

Multiple sclerosis (MS), also known as encephalomyelitis disseminata, is a demyelinating disease in which the insulating covers of nerve cells in the brain and spinal cord are damaged. This damage disrupts the ability of parts of the nervous system to transmit signals, resulting in a range of signs and symptoms, including physical, mental, and sometimes psychiatric problems. Specific symptoms can include double vision, blindness in one eye, muscle weakness and trouble with sensation or coordination. MS takes several forms, with new symptoms either occurring in isolated attacks (relapsing forms) or building up over time (progressive forms). Between attacks, symptoms may disappear completely; however, permanent neurological problems often remain, especially as the disease advances.

While the cause is unclear, the underlying mechanism is thought to be either destruction by the immune system or failure of the myelin-producing cells. Proposed causes for this include genetics and environmental factors being triggered by a viral infection. MS is usually diagnosed based on the presenting signs and symptoms and the results of supporting medical tests.

There is no known cure for multiple sclerosis. Treatments attempt to improve function after an attack and prevent new attacks. Medications used to treat MS, while modestly effective, can have side effects and be poorly tolerated. Physical therapy can help with people's ability to function. Many people pursue alternative treatments, despite a lack of evidence of benefit. The long-term outcome is difficult to predict; good outcomes are more often seen in women, those who develop the disease early in life, those with a relapsing course, and those who initially experienced few attacks. Life expectancy is on average five to ten years lower than that of the unaffected population.

Multiple sclerosis is the most common immune-mediated disorder affecting the central nervous system. In 2015, about 2.3 million people were affected globally, with rates varying widely in different regions and among different populations. In that year, about 18,900 people died from MS, up from 12,000 in 1990. The disease usually begins between the ages of twenty and fifty and is twice as common in women as in men. MS was first described in 1868 by French neurologist Jean-Martin Charcot. The name multiple sclerosis refers to the numerous glial scars (or sclerae – essentially plaques or lesions) that develop on the white matter of the brain and spinal cord. A number of new treatments and diagnostic methods are under development.

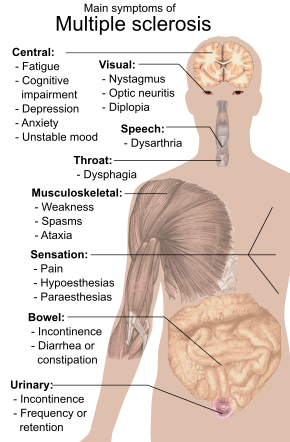

Signs and symptoms

A person with MS can have almost any neurological symptom or sign, with autonomic, visual, motor, and sensory problems being the most common. The specific symptoms are determined by the locations of the lesions within the nervous system, and may include loss of sensitivity or changes in sensation such as tingling, pins and needles or numbness, muscle weakness, blurred vision, very pronounced reflexes, muscle spasms, or difficulty in moving; difficulties with coordination and balance (ataxia); problems with speech or swallowing, visual problems (nystagmus, optic neuritis or double vision), feeling tired, acute or chronic pain, and bladder and bowel difficulties (such as neurogenic bladder), among others.

Difficulties thinking and emotional problems such as depression or unstable mood are also common. Uhthoff's phenomenon, a worsening of symptoms due to exposure to higher than usual temperatures, and Lhermitte's sign, an electrical sensation that runs down the back when bending the neck, are particularly characteristic of MS. The main measure of disability and severity is the expanded disability status scale (EDSS), with other measures such as the multiple sclerosis functional composite being increasingly used in research.

The condition begins in 85% of cases as a clinically isolated syndrome (CIS) over a number of days with 45% having motor or sensory problems, 20% having optic neuritis, and 10% having symptoms related to brainstem dysfunction, while the remaining 25% have more than one of the previous difficulties. The course of symptoms occurs in two main patterns initially: either as episodes of sudden worsening that last a few days to months (called relapses, exacerbations, bouts, attacks, or flare-ups) followed by improvement (85% of cases) or as a gradual worsening over time without periods of recovery (10–15% of cases). A combination of these two patterns may also occur or people may start in a relapsing and remitting course that then becomes progressive later on.

Relapses are usually not predictable, occurring without warning. Exacerbations rarely occur more frequently than twice per year. Some relapses, however, are preceded by common triggers and they occur more frequently during spring and summer. Similarly, viral infections such as the common cold, influenza, or gastroenteritis increase their risk. Stress may also trigger an attack. Women with MS who become pregnant experience fewer relapses; however, during the first months after delivery the risk increases. Overall, pregnancy does not seem to influence long-term disability. Many events have been found not to affect relapse rates including vaccination, breast feeding, physical trauma, and Uhthoff's phenomenon.

Causes

The cause of MS is unknown; however, it is believed to occur as a result of some combination of genetic and environmental factors such as infectious agents. Theories try to combine the data into likely explanations, but none has proved definitive. While there are a number of environmental risk factors and although some are partly modifiable, further research is needed to determine whether their elimination can prevent MS.

Geography

MS is more common in people who live farther from the equator, although exceptions exist. These exceptions include ethnic groups that are at low risk far from the equator such as the Samis, Amerindians, Canadian Hutterites, New Zealand Māori, and Canada's Inuit, as well as groups that have a relatively high risk close to the equator such as Sardinians, inland Sicilians, Palestinians, and Parsi. The cause of this geographical pattern is not clear. While the north–south gradient of incidence is decreasing, as of 2010 it is still present.

MS is more common in regions with northern European populations and the geographic variation may simply reflect the global distribution of these high-risk populations. Decreased sunlight exposure resulting in decreased vitamin D production has also been put forward as an explanation.

A relationship between season of birth and MS lends support to this idea, with fewer people born in the northern hemisphere in November as compared to May being affected later in life.

Environmental factors may play a role during childhood, with several studies finding that people who move to a different region of the world before the age of 15 acquire the new region's risk to MS. If migration takes place after age 15, however, the person retains the risk of their home country. There is some evidence that the effect of moving may still apply to people older than 15.

Genetics

MS is not considered a hereditary disease; however, a number of genetic variations have been shown to increase the risk. Some of these genes appear to have higher levels of expression in microglial cells than expected by chance. The probability of developing the disease is higher in relatives of an affected person, with a greater risk among those more closely related. In identical twins both are affected about 30% of the time, while around 5% for non-identical twins and 2.5% of siblings are affected with a lower percentage of half-siblings. If both parents are affected the risk in their children is 10 times that of the general population. MS is also more common in some ethnic groups than others.

Specific genes that have been linked with MS include differences in the human leukocyte antigen (HLA) system—a group of genes on chromosome 6 that serves as the major histocompatibility complex (MHC). That differences in the HLA region are related to susceptibility has been known since the 1980s, and this same region has also been implicated in the development of other autoimmune diseases such as diabetes type I and systemic lupus erythematosus. The most consistent finding is the association between multiple sclerosis and alleles of the MHC defined as DR15 and DQ6. Other loci have shown a protective effect, such as HLA-C554 and HLA-DRB1*11. Overall, it has been estimated that HLA differences account for between 20% and 60% of the genetic predisposition. Modern genetic methods (genome-wide association studies) have revealed at least twelve other genes outside the HLA locus that modestly increase the probability of MS.

Infectious agents

Many microbes have been proposed as triggers of MS, but none have been confirmed. Moving at an early age from one location in the world to another alters a person's subsequent risk of MS. An explanation for this could be that some kind of infection, produced by a widespread microbe rather than a rare one, is related to the disease. Proposed mechanisms include the hygiene hypothesis and the prevalence hypothesis. The hygiene hypothesis proposes that exposure to certain infectious agents early in life is protective, the disease is a response to a late encounter with such agents. The prevalence hypothesis proposes that the disease is due to an infectious agent more common in regions where MS is common and where, in most individuals, it causes an ongoing infection without symptoms. Only in a few cases and after many years does it cause demyelination. The hygiene hypothesis has received more support than the prevalence hypothesis.

Evidence for a virus as a cause include the presence of oligoclonal bands in the brain and cerebrospinal fluid of most people with MS, the association of several viruses with human demyelination encephalomyelitis, and the occurrence of demyelination in animals caused by some viral infections. Human herpes viruses are a candidate group of viruses. Individuals having never been infected by the Epstein–Barr virus are at a reduced risk of getting MS, whereas those infected as young adults are at a greater risk than those having had it at a younger age. Although some consider that this goes against the hygiene hypothesis, since the non-infected have probably experienced a more hygienic upbringing, others believe that there is no contradiction, since it is a first encounter with the causative virus relatively late in life that is the trigger for the disease. Other diseases that may be related include measles, mumps and rubella.

Other

Smoking may be an independent risk factor for MS. Stress may be a risk factor, although the evidence to support this is weak. Association with occupational exposures and toxins—mainly solvents—has been evaluated, but no clear conclusions have been reached. Vaccinations were studied as causal factors; however, most studies show no association. Several other possible risk factors, such as diet and hormone intake, have been looked at; however, evidence on their relation with the disease is "sparse and unpersuasive". Gout occurs less than would be expected and lower levels of uric acid have been found in people with MS. This has led to the theory that uric acid is protective, although its exact importance remains unknown.

Pathophysiology

The three main characteristics of MS are the formation of lesions in the central nervous system (also called plaques), inflammation, and the destruction of myelin sheaths of neurons. These features interact in a complex and not yet fully understood manner to produce the breakdown of nerve tissue and in turn the signs and symptoms of the disease. Cholesterol crystals are believed to both impair myelin repair and aggravate inflammation. MS is believed to be an immune-mediated disorder that develops from an interaction of the individual's genetics and as yet unidentified environmental causes. Damage is believed to be caused, at least in part, by attack on the nervous system by a person's own immune system.

Lesions

The name multiple sclerosis refers to the scars (sclerae – better known as plaques or lesions) that form in the nervous system. These lesions most commonly affect the white matter in the optic nerve, brain stem, basal ganglia, and spinal cord, or white matter tracts close to the lateral ventricles. The function of white matter cells is to carry signals between grey matter areas, where the processing is done, and the rest of the body. The peripheral nervous system is rarely involved.

To be specific, MS involves the loss of oligodendrocytes, the cells responsible for creating and maintaining a fatty layer—known as the myelin sheath—which helps the neurons carry electrical signals (action potentials). This results in a thinning or complete loss of myelin and, as the disease advances, the breakdown of the axons of neurons. When the myelin is lost, a neuron can no longer effectively conduct electrical signals. A repair process, called remyelination, takes place in early phases of the disease, but the oligodendrocytes are unable to completely rebuild the cell's myelin sheath. Repeated attacks lead to successively less effective remyelinations, until a scar-like plaque is built up around the damaged axons. These scars are the origin of the symptoms and during an attack magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) often shows more than ten new plaques. This could indicate that there are a number of lesions below which the brain is capable of repairing itself without producing noticeable consequences. Another process involved in the creation of lesions is an abnormal increase in the number of astrocytes due to the destruction of nearby neurons. A number of lesion patterns have been described.

Inflammation

Apart from demyelination, the other sign of the disease is inflammation. Fitting with an immunological explanation, the inflammatory process is caused by T cells, a kind of lymphocyte that plays an important role in the body's defenses. T cells gain entry into the brain via disruptions in the blood–brain barrier. The T cells recognize myelin as foreign and attack it, explaining why these cells are also called "autoreactive lymphocytes".

The attack on myelin starts inflammatory processes, which triggers other immune cells and the release of soluble factors like cytokines and antibodies. A further breakdown of the blood-brain barrier, in turn, causes a number of other damaging effects such as swelling, activation of macrophages, and more activation of cytokines and other destructive proteins. Inflammation can potentially reduce transmission of information between neurons in at least three ways. The soluble factors released might stop neurotransmission by intact neurons. These factors could lead to or enhance the loss of myelin, or they may cause the axon to break down completely.

Blood–brain barrier

The blood–brain barrier (BBB) is a part of the capillary system that prevents the entry of T cells into the central nervous system. It may become permeable to these types of cells secondary to an infection by a virus or bacteria. After it repairs itself, typically once the infection has cleared, T cells may remain trapped inside the brain. Gadolinium cannot cross a normal BBB and, therefore, gadolinium-enhanced MRI is used to show BBB breakdowns.

Diagnosis

28/MSMRIMark.png/220px-MSMRIMark.png" decoding="async" width="220" height="274" class="thumbimage" srcset="//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/2/28/MSMRIMark.png/330px-MSMRIMark.png 1.5x, //upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/2/28/MSMRIMark.png/440px-MSMRIMark.png 2x" data-file-width="756" data-file-height="942">

28/MSMRIMark.png/220px-MSMRIMark.png" decoding="async" width="220" height="274" class="thumbimage" srcset="//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/2/28/MSMRIMark.png/330px-MSMRIMark.png 1.5x, //upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/2/28/MSMRIMark.png/440px-MSMRIMark.png 2x" data-file-width="756" data-file-height="942"> Multiple sclerosis is typically diagnosed based on the presenting signs and symptoms, in combination with supporting medical imaging and laboratory testing. It can be difficult to confirm, especially early on, since the signs and symptoms may be similar to those of other medical problems. The McDonald criteria, which focus on clinical, laboratory, and radiologic evidence of lesions at different times and in different areas, is the most commonly used method of diagnosis with the Schumacher and Poser criteria being of mostly historical significance.

Clinical data alone may be sufficient for a diagnosis of MS if an individual has had separate episodes of neurological symptoms characteristic of the disease. In those who seek medical attention after only one attack, other testing is needed for the diagnosis. The most commonly used diagnostic tools are neuroimaging, analysis of cerebrospinal fluid and evoked potentials. Magnetic resonance imaging of the brain and spine may show areas of demyelination (lesions or plaques). Gadolinium can be administered intravenously as a contrast agent to highlight active plaques and, by elimination, demonstrate the existence of historical lesions not associated with symptoms at the moment of the evaluation. Testing of cerebrospinal fluid obtained from a lumbar puncture can provide evidence of chronic inflammation in the central nervous system. The cerebrospinal fluid is tested for oligoclonal bands of IgG on electrophoresis, which are inflammation markers found in 75–85% of people with MS. The nervous system in MS may respond less actively to stimulation of the optic nerve and sensory nerves due to demyelination of such pathways. These brain responses can be examined using visual- and sensory-evoked potentials.

While the above criteria allow for a non-invasive diagnosis, and even though some state that the only definitive proof is an autopsy or biopsy where lesions typical of MS are detected, currently, as of 2017, there is no single test (including biopsy) that can provide a definitive diagnosis of this disease.

Types and variants

Several phenotypes (commonly termed types), or patterns of progression, have been described. Phenotypes use the past course of the disease in an attempt to predict the future course. They are important not only for prognosis but also for treatment decisions. Currently, the United States National Multiple Sclerosis Society and the Multiple Sclerosis International Federation, describes four types of MS (revised in 2013):

- Clinically isolated syndrome (CIS)

- Relapsing-remitting MS (RRMS)

- Primary progressive MS (PPMS)

- Secondary progressive MS (SPMS)

Relapsing-remitting MS is characterized by unpredictable relapses followed by periods of months to years of relative quiet (remission) with no new signs of disease activity. Deficits that occur during attacks may either resolve or leave problems, the latter in about 40% of attacks and being more common the longer a person has had the disease. This describes the initial course of 80% of individuals with MS.

The relapsing-remitting subtype usually begins with a clinically isolated syndrome (CIS). In CIS, a person has an attack suggestive of demyelination, but does not fulfill the criteria for multiple sclerosis. 30 to 70% of persons who experience CIS, later develop MS.

Primary progressive MS occurs in approximately 10–20% of individuals, with no remission after the initial symptoms. It is characterized by progression of disability from onset, with no, or only occasional and minor, remissions and improvements. The usual age of onset for the primary progressive subtype is later than of the relapsing-remitting subtype. It is similar to the age that secondary progressive usually begins in relapsing-remitting MS, around 40 years of age.

Secondary progressive MS occurs in around 65% of those with initial relapsing-remitting MS, who eventually have progressive neurologic decline between acute attacks without any definite periods of remission. Occasional relapses and minor remissions may appear. The most common length of time between disease onset and conversion from relapsing-remitting to secondary progressive MS is 19 years.

Multiple sclerosis behaves differently in children, taking more time to reach the progressive stage. Nevertheless, they still reach it at a lower average age than adults usually do.

Special courses

Independently of the types published by the MS associations, regulatory agencies like the FDA often consider special courses, trying to reflect some clinical trials results on their approval documents. Some examples could be "Highly Active MS" (HAMS), "Active Secondary MS" (similar to the old Progressive-Relapsing) and "Rapidly progressing PPMS".

Also, when deficits always resolve between attacks, this is sometimes referred to as benign MS, although people will still build up some degree of disability in the long term. On the other hand, the term malignant multiple sclerosis is used to describe people with MS having reached significant level of disability in a short period.

As of June 2020 an international panel has published a standardized definition for the course HAMS

Variants

Atypical variants of MS have been described; these include tumefactive multiple sclerosis, Balo concentric sclerosis, Schilder's diffuse sclerosis, and Marburg multiple sclerosis. There is debate on whether they are MS variants or different diseases. Some diseases previously considered MS variants like Devic's disease are now considered outside the MS spectrum.

Management

Although there is no known cure for multiple sclerosis, several therapies have proven helpful. The primary aims of therapy are returning function after an attack, preventing new attacks, and preventing disability. Starting medications is generally recommended in people after the first attack when more than two lesions are seen on MRI.

As with any medical treatment, medications used in the management of MS have several adverse effects. Alternative treatments are pursued by some people, despite the shortage of supporting evidence.

Acute attacks

During symptomatic attacks, administration of high doses of intravenous corticosteroids, such as methylprednisolone, is the usual therapy, with oral corticosteroids seeming to have a similar efficacy and safety profile. Although effective in the short term for relieving symptoms, corticosteroid treatments do not appear to have a significant impact on long-term recovery. The long term benefit is unclear in optic neuritis as of 2020. The consequences of severe attacks that do not respond to corticosteroids might be treatable by plasmapheresis.

Disease-modifying treatments

Relapsing remitting multiple sclerosis

As of 2020, multiple disease-modifying medications are approved by regulatory agencies for relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis (RRMS). They are interferon beta-1a, interferon beta-1b, glatiramer acetate, mitoxantrone, natalizumab, fingolimod, teriflunomide, dimethyl fumarate, alemtuzumab, ocrelizumab, siponimod, cladribine, and ozanimod.

Their cost effectiveness as of 2012 is unclear. In March 2017, the FDA approved ocrelizumab, a humanized anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody, as a treatment for RRMS, with requirements for several Phase IV clinical trials.

In RRMS they are modestly effective at decreasing the number of attacks. The interferons and glatiramer acetate are first-line treatments and are roughly equivalent, reducing relapses by approximately 30%. Early-initiated long-term therapy is safe and improves outcomes. Natalizumab reduces the relapse rate more than first-line agents; however, due to issues of adverse effects is a second-line agent reserved for those who do not respond to other treatments or with severe disease. Mitoxantrone, whose use is limited by severe adverse effects, is a third-line option for those who do not respond to other medications.

Treatment of clinically isolated syndrome (CIS) with interferons decreases the chance of progressing to clinical MS. Efficacy of interferons and glatiramer acetate in children has been estimated to be roughly equivalent to that of adults. The role of some newer agents such as fingolimod, teriflunomide, and dimethyl fumarate, is not yet entirely clear. It is difficult to make firm conclusions about the best treatment, especially regarding the long‐term benefit and safety of early treatment, given the lack of studies directly comparing disease modifying therapies or long-term monitoring of patient outcomes.

As of 2017, rituximab was widely used off-label to treat RRMS. There is a lack of high quality randomised control trials examining rituximab versus placebo or other disease-modifying therapies, and as such the benefits of rituximab for relapsing remitting multiple sclerosis remain inconclusive.

The relative effectiveness of different treatments is unclear, as most have only been compared to placebo or a small number of other therapies. Direct comparisons of interferons and glatiramer acetate indicate similar effects or only small differences in effects on relapse rate, disease progression and magnetic resonance imaging measures. Alemtuzumab, natalizumab, and fingolimod may be more effective than other drugs in reducing relapses over the short term in people with RRMS. Natalizumab and interferon beta-1a (Rebif) may reduce relapses compared to both placebo and interferon beta-1a (Avonex) while Interferon beta-1b (Betaseron), glatiramer acetate, and mitoxantrone may also prevent relapses. Evidence on relative effectiveness in reducing disability progression is unclear. All medications are associated with adverse effects that may influence their risk to benefit profiles.

Progressive multiple sclerosis

As of 2013, review of 9 immunomodulators and immunosuppressants found no evidence of any being effective in preventing disability progression in people with progressive MS.

As of 2017, rituximab has been widely used off-label to treat progressive primary MS. In March 2017 the FDA approved ocrelizumab as a treatment for primary progressive MS, the first drug to gain that approval, with requirements for several Phase IV clinical trials.

As of 2011[update], only one medication, mitoxantrone, had been approved for secondary progressive MS. In this population tentative evidence supports mitoxantrone moderately slowing the progression of the disease and decreasing rates of relapses over two years.

In 2017, ocrelizumab was approved in the United States for the treatment of primary progressive multiple sclerosis in adults. It is also used for the treatment of relapsing forms of multiple sclerosis, to include clinically isolated syndrome, relapsing-remitting disease, and active secondary progressive disease in adults.

In 2019, siponimod and cladribine were approved in the United States for the treatment of secondary progressive multiple sclerosis.

Adverse effects

The disease-modifying treatments have several adverse effects. One of the most common is irritation at the injection site for glatiramer acetate and the interferons (up to 90% with subcutaneous injections and 33% with intramuscular injections). Over time, a visible dent at the injection site, due to the local destruction of fat tissue, known as lipoatrophy, may develop. Interferons may produce flu-like symptoms; some people taking glatiramer experience a post-injection reaction with flushing, chest tightness, heart palpitations, and anxiety, which usually lasts less than thirty minutes. More dangerous but much less common are liver damage from interferons, systolic dysfunction (12%), infertility, and acute myeloid leukemia (0.8%) from mitoxantrone, and progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy occurring with natalizumab (occurring in 1 in 600 people treated).

Fingolimod may give rise to hypertension and slowed heart rate, macular edema, elevated liver enzymes or a reduction in lymphocyte levels. Tentative evidence supports the short-term safety of teriflunomide, with common side effects including: headaches, fatigue, nausea, hair loss, and limb pain. There have also been reports of liver failure and PML with its use and it is dangerous for fetal development. Most common side effects of dimethyl fumarate are flushing and gastrointestinal problems. While dimethyl fumarate may lead to a reduction in the white blood cell count there were no reported cases of opportunistic infections during trials.

Associated symptoms

Both medications and neurorehabilitation have been shown to improve some symptoms, though neither changes the course of the disease. Some symptoms have a good response to medication, such as bladder spasticity, while others are little changed. Equipment such as catheters for neurogenic bladder or mobility aids can be helpful in improving functional status.

A multidisciplinary approach is important for improving quality of life; however, it is difficult to specify a 'core team' as many health services may be needed at different points in time. Multidisciplinary rehabilitation programs increase activity and participation of people with MS but do not influence impairment level. Studies investigating information provision in support of patient understanding and participation suggest that while interventions (written information, decision aids, coaching, educational programmes) may increase knowledge, the evidence of an effect on decision making and quality of life is mixed and low certainty. There is limited evidence for the overall efficacy of individual therapeutic disciplines, though there is good evidence that specific approaches, such as exercise, and psychological therapies are effective. Cognitive training, alone or combined with other neuropsychological interventions, may show positive effects for memory and attention though firm conclusions are not currently possible given small sample numbers, variable methodology, interventions and outcome measures. The effectiveness of palliative approaches in addition to standard care is uncertain, due to lack of evidence. The effectiveness of interventions, including exercise, specifically for the prevention of falls in people with MS is uncertain, while there is some evidence of an effect on balance function and mobility. Cognitive behavioral therapy has shown to be moderately effective for reducing MS fatigue. The evidence for the effectiveness of non-pharmacological interventions for chronic pain is insufficient to recommend such interventions alone, however their use in combination with medications may be reasonable.

Alternative treatments

Over 50% of people with MS may use complementary and alternative medicine, although percentages vary depending on how alternative medicine is defined. Regarding the characteristics of users, they are more frequently women, have had MS for a longer time, tend to be more disabled and have lower levels of satisfaction with conventional healthcare. The evidence for the effectiveness for such treatments in most cases is weak or absent. Treatments of unproven benefit used by people with MS include dietary supplementation and regimens, vitamin D, relaxation techniques such as yoga, herbal medicine (including medical cannabis), hyperbaric oxygen therapy, self-infection with hookworms, reflexology, acupuncture, and mindfulness. Evidence suggests vitamin D supplementation, irrespective of the form and dose, provides no benefit for people with MS; this includes for measures such as relapse recurrence, disability, and MRI lesions while effects on health‐related quality of life and fatigue are unclear.

High-dose biotin (300 mg/day = 10,000 times adequate intake) has been clinical trialed for treatment of multiple sclerosis. The hypothesis is that biotin may promote remyelination of the myelin sheath of nerve cells, slowing or even reversing neurodegeneration. The proposed mechanisms are that biotin activates acetyl-coA carboxylase, which is a key rate-limiting enzyme during the synthesis of myelin and by reducing axonal hypoxia through enhanced energy production. Two reviews reported no benefits, and some evidence for increased disease activity and higher risk of relapse.

Prognosis

The expected future course of the disease depends on the subtype of the disease; the individual's sex, age, and initial symptoms; and the degree of disability the person has. Female sex, relapsing-remitting subtype, optic neuritis or sensory symptoms at onset, few attacks in the initial years and especially early age at onset, are associated with a better course.

The average life expectancy is 30 years from the start of the disease, which is 5 to 10 years less than that of unaffected people. Almost 40% of people with MS reach the seventh decade of life. Nevertheless, two-thirds of the deaths are directly related to the consequences of the disease. Suicide is more common, while infections and other complications are especially dangerous for the more disabled. Although most people lose the ability to walk before death, 90% are capable of independent walking at 10 years from onset, and 75% at 15 years.

Epidemiology

MS is the most common autoimmune disorder of the central nervous system. As of 2010, the number of people with MS was 2–2.5 million (approximately 30 per 100,000) globally, with rates varying widely in different regions. It is estimated to have resulted in 18,000 deaths that year. In Africa rates are less than 0.5 per 100,000, while they are 2.8 per 100,000 in South East Asia, 8.3 per 100,000 in the Americas, and 80 per 100,000 in Europe. Rates surpass 200 per 100,000 in certain populations of Northern European descent. The number of new cases that develop per year is about 2.5 per 100,000.

Rates of MS appear to be increasing; this, however, may be explained simply by better diagnosis. Studies on populational and geographical patterns have been common and have led to a number of theories about the cause.

MS usually appears in adults in their late twenties or early thirties but it can rarely start in childhood and after 50 years of age. The primary progressive subtype is more common in people in their fifties. Similarly to many autoimmune disorders, the disease is more common in women, and the trend may be increasing. As of 2008, globally it is about two times more common in women than in men. In children, it is even more common in females than males, while in people over fifty, it affects males and females almost equally.

History

Medical discovery

Robert Carswell (1793–1857), a British professor of pathology, and Jean Cruveilhier (1791–1873), a French professor of pathologic anatomy, described and illustrated many of the disease's clinical details, but did not identify it as a separate disease. Specifically, Carswell described the injuries he found as "a remarkable lesion of the spinal cord accompanied with atrophy". Under the microscope, Swiss pathologist Georg Eduard Rindfleisch (1836–1908) noted in 1863 that the inflammation-associated lesions were distributed around blood vessels.

The French neurologist Jean-Martin Charcot (1825–1893) was the first person to recognize multiple sclerosis as a distinct disease in 1868. Summarizing previous reports and adding his own clinical and pathological observations, Charcot called the disease sclerose en plaques.

Diagnosis history

The first attempt to establish a set of diagnostic criteria was also due to Charcot in 1868. He published what now is known as the "Charcot Triad", consisting in nystagmus, intention tremor, and telegraphic speech (scanning speech) Charcot also observed cognition changes, describing his patients as having a "marked enfeeblement of the memory" and "conceptions that formed slowly".

Diagnosis was based on Charcot triad and clinical observation until Schumacher made the first attempt to standardize criteria in 1965 by introducing some fundamental requirements: Dissemination of the lesions in time (DIT) and space (DIS), and that "signs and symptoms cannot be explained better by another disease process". Both requirements were later inherited by Poser criteria and McDonald criteria, whose 2010 version is currently in use.

During the 20th century, theories about the cause and pathogenesis were developed and effective treatments began to appear in the 1990s. Since the beginning of the 21st century, refinements of the concepts have taken place. The 2010 revision of the McDonald criteria allowed for the diagnosis of MS with only one proved lesion (CIS).

In 1996, the US National Multiple Sclerosis Society (NMSS) (Advisory Committee on Clinical Trials) defined the first version of the clinical phenotypes that is currently in use. In this first version they provided standardized definitions for 4 MS clinical courses: relapsing-remitting (RR), secondary progressive (SP), primary progressive (PP), and progressive relapsing (PR). In 2010, PR was dropped and CIS was incorporated. Subsequently, three years later, the 2013 revision of the "phenotypes for the disease course" were forced to consider CIS as one of the phenotypes of MS, making obsolete some expressions like "conversion from CIS to MS". Other organizations have proposed later new clinical phenotypes, like HAMS (Highly Active MS) as result of the work in DMT approval processes.