Melas

Summary

Clinical characteristics.

MELAS (mitochondrial encephalomyopathy, lactic acidosis, and stroke-like episodes) is a multisystem disorder with protean manifestations. The vast majority of affected individuals develop signs and symptoms of MELAS between ages two and 40 years. Common clinical manifestations include stroke-like episodes, encephalopathy with seizures and/or dementia, muscle weakness and exercise intolerance, normal early psychomotor development, recurrent headaches, recurrent vomiting, hearing impairment, peripheral neuropathy, learning disability, and short stature. During the stroke-like episodes neuroimaging shows increased T2-weighted signal areas that do not correspond to the classic vascular distribution (hence the term "stroke-like"). Lactic acidemia is very common and muscle biopsies typically show ragged red fibers.

Diagnosis/testing.

The diagnosis of MELAS is based on meeting clinical diagnostic criteria and identifying a pathogenic variant in one of the genes associated with MELAS. The m.3243A>G pathogenic variant in the mitochondrial gene MT-TL1 is present in approximately 80% of individuals with MELAS. Pathogenic variants in MT-TL1 or other mtDNA genes, particularly MT-ND5, can also cause this disorder.

Management.

Treatment of manifestations: Treatment for MELAS is generally supportive. During the acute stroke-like episode, a bolus of intravenous arginine (500 mg/kg for children or 10 g/m2 body surface area for adults) within three hours of symptom onset is recommended followed by the administration of a similar dosage of intravenous arginine as a continuous infusion over 24 hours for the next three to five days. Coenzyme Q10, L-carnitine, and creatine have been beneficial in some individuals. Sensorineural hearing loss has been treated with cochlear implantation; seizures respond to traditional anticonvulsant therapy (although valproic acid should be avoided). Ptosis, cardiomyopathy, cardiac conduction defects, nephropathy, and migraine headache are treated in the standard manner. Diabetes mellitus is managed by dietary modification, oral hypoglycemic agents, or insulin therapy. Exercise intolerance and weakness may respond to aerobic exercise.

Prevention of primary manifestations: Once an individual with MELAS has the first stroke-like episode, arginine should be administered prophylactically to reduce the risk of recurrent stroke-like episodes. A daily dose of 150 to 300 mg/kg/day oral arginine in three divided doses is recommended.

Prevention of secondary complications: Because febrile illnesses may trigger acute exacerbations, individuals with MELAS should receive standard childhood vaccinations, flu vaccine, and pneumococcal vaccine.

Surveillance: Affected individuals and their at-risk relatives should be followed at regular intervals to monitor progression and the appearance of new symptoms. Annual ophthalmologic, audiology, and cardiologic (electrocardiogram and echocardiogram) evaluations are recommended. Annual urinalysis and fasting blood glucose level are also recommended.

Agents/circumstances to avoid: Mitochondrial toxins, including aminoglycoside antibiotics, linezolid, cigarettes, and alcohol; valproic acid for seizure treatment; metformin because of its propensity to cause lactic acidosis; dichloroacetate (DCA) because of increased risk for peripheral neuropathy.

Pregnancy management: Affected or at-risk pregnant women should be monitored for diabetes mellitus and respiratory insufficiency, which may require therapeutic interventions

Genetic counseling.

MELAS is caused by pathogenic variants in mtDNA and is transmitted by maternal inheritance. The father of a proband is not at risk of having the mtDNA pathogenic variant. The mother of a proband usually has the mtDNA pathogenic variant and may or may not have symptoms. A man with a mtDNA pathogenic variant cannot transmit the variant to any of his offspring. A woman with a mtDNA pathogenic variant (whether symptomatic or asymptomatic) transmits the variant to all of her offspring. Prenatal testing and preimplantation genetic testing for MELAS is possible if a mtDNA pathogenic variant has been detected in the mother. However, because the mutational load in embryonic and fetal tissues sampled (i.e., amniocytes and chorionic villi) may not correspond to that of all fetal tissues, and because the mutational load in tissues sampled prenatally may shift in utero or after birth as a result of random mitotic segregation, prediction of the phenotype from prenatal studies cannot be made with certainty.

Diagnosis

Clinical diagnostic criteria for MELAS (mitochondrial encephalomyopathy, lactic acidosis, and stroke-like episodes) have been published [Hirano et al 1992, Yatsuga et al 2012] (see Establishing the Diagnosis).

Suggestive Findings

MELAS (mitochondrial encephalomyopathy, lactic acidosis, and stroke-like episodes) should be suspected in individuals with the following features.

Clinical Features

- Stroke-like episodes before the age of 40 years

- Acquired encephalopathy with seizures and/or dementia

- Recurrent headaches

- Muscle weakness and exercise intolerance

- Cortical vision loss

- Hemiparesis

- Recurrent vomiting

- Short stature

- Hearing impairment

- Normal early psychomotor development

- Peripheral neuropathy

- Learning disability

Brain Imaging

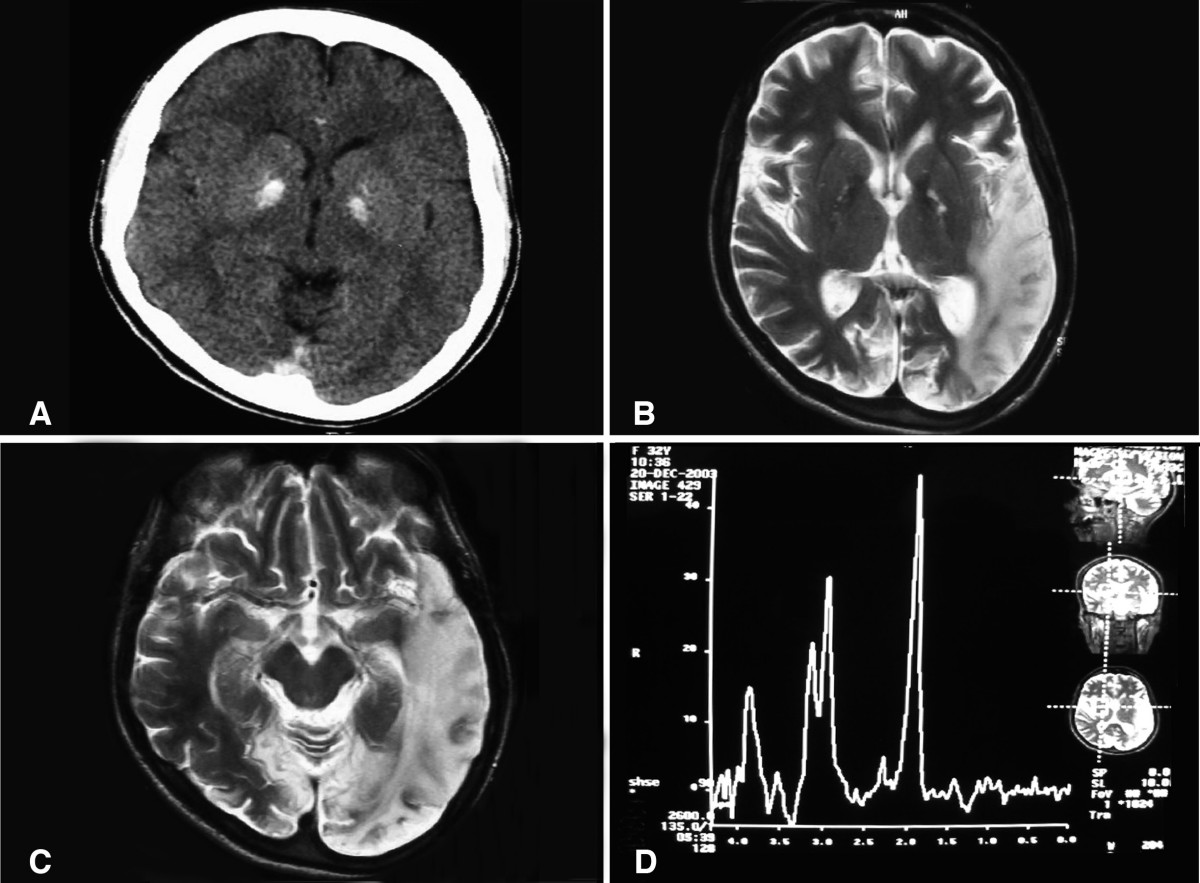

Brain MRI

- During the stroke-like episodes, the affected areas:

- Have increased T2 signal;

- Do not correspond to the classic vascular distribution (hence the term "stroke-like");

- Are asymmetric;

- Typically involve predominantly the posterior cerebrum (temporal, parietal, and occipital lobes);

- Can be restricted to cortical areas or involve subcortical white matter [Hirano et al1992, Sproule & Kaufmann 2008].

- Slow spreading of the stroke-like lesions occurs in the weeks following the first symptoms, typically documented by T2-weighted MRI [Iizuka et al 2003].

- Diffusion-weighted MRI shows increased apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) in the stroke-like lesions of MELAS, in contrast to the decreased ADC seen in ischemic strokes [Kolb et al 2003].

- MR angiography is usually normal and MR spectroscopy shows decreased N-acetylaspartate signals and accumulation of lactate [Sproule & Kaufmann 2008].

Head CT. Basal ganglia calcifications are occasionally seen.

Electromyography and Nerve Conduction Studies

Findings are consistent with a myopathic process, but neuropathy may coexist. Neuropathy can be axonal or mixed axonal and demyelinating [Kärppä et al 2003, Kaufmann et al 2006b].

Suggestive Laboratory Findings

Lactic acidosis both in blood and CSF. Lactic acidemia is very common. CSF lactate is also elevated in most affected individuals.

Lactic acidemia is not specific for MELAS syndrome as it can occur in other mitochondrial diseases, metabolic diseases, and systemic illness. Other situations (unrelated to the diagnosis of MELAS) in which lactate can be elevated are acute neurologic events such as seizure or stroke. On the other hand, lactate level can be normal in a minority of individuals with MELAS syndrome [Hirano & Pavlakis 1994].

Elevated CSF protein rarely surpasses 100 mg/dL.

Muscle biopsy

- Ragged red fibers (RRFs) with the modified Gomori trichrome stain, which represent mitochondrial proliferation below the plasma membrane of the muscular fibers causing the contour of the muscle fiber to become irregular. These proliferated mitochondria also stain strongly with the succinate dehydrogenase (SDH) stain giving the appearance of ragged blue fibers.Although RRFs are present in many other mitochondrial diseases e.g., MERRF (myoclonic epilepsy with ragged red fibers), most of the RRFs in MELAS stain positively with the cytochrome c oxidase (COX) histochemical stain, unlike other mitochondrial diseases where RRFs do not react with COX.

- An overabundance of mitochondria in smooth muscle and endothelial cells of intramuscular blood vessels, best revealed with the SDH stain ("strongly succinate dehydrogenase-reactive blood vessels," or SSVs)

- Respiratory chain studies on muscle tissue: typically multiple partial defects, especially involving complex I and/or complex IV. However, biochemical results can also be normal.

Note: Muscle biopsy is not required to make this diagnosis; molecular genetic testing is frequently used in lieu of muscle biopsy to establish the diagnosis.

Establishing the Diagnosis

Two sets of clinical diagnostic criteria for MELAS (mitochondrial encephalomyopathy, lactic acidosis, and stroke-like episodes) have been published:

- I.

A clinical diagnosis of MELAS can be made if the following three criteria are met [Hirano et al 1992]:

- Stroke-like episodes before age 40 years

- Encephalopathy characterized by seizures and/or dementia

- Mitochondrial myopathy is evident by the presence of lactic acidosis and/or ragged-red fibers (RRFs) on muscle biopsy.

AND at least two of the following criteria are present:

- Normal early psychomotor development

- Recurrent headaches

- Recurrent vomiting episodes

- II.

A clinical diagnosis of MELAS can also be made in an individual with at least two category A and two category B criteria [Yatsuga et al 2012]:

Category A criteria

- Headaches with vomiting

- Seizures

- Hemiplegia

- Cortical blindness

- Acute focal lesions on neuroimaging (see Suggestive Findings, Brain Imaging)

Category B criteria

- High plasma or cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) lactate

- Mitochondrial abnormalities on muscle biopsy (see Suggestive Findings, Suggestive Laboratory Findings).

- A MELAS-related pathogenic variant (see Table 1)

The diagnosis of MELAS is established in a proband who meets the clinical diagnostic criteria discussed above and who has a pathogenic variant in one of the genes listed in Table 1 identified by molecular genetic testing.

Note: Pathogenic variants can usually be detected in mtDNA from leukocytes in individuals with typical MELAS; however, the occurrence of "heteroplasmy" in disorders of mtDNA can result in varying tissue distribution of mutated mtDNA. Hence, the pathogenic variant may be undetectable in mtDNA from leukocytes and may be detected only in other tissues, such as buccal mucosa, cultured skin fibroblasts, hair follicles, urinary sediment, or (most reliably) skeletal muscle.

Molecular genetic testing approaches can include a combination of gene-targeted testing (single-gene testing, concurrent or serial single-gene testing, multigene panel) and comprehensive genomic testing (exome sequencing, exome array, genome sequencing) depending on the phenotype.

Gene-targeted testing requires that the clinician determine which gene(s) are likely involved, whereas genomic testing does not. Individuals with the distinctive findings described in Suggestive Findings are likely to be diagnosed using gene-targeted testing (see Option 1), whereas those with a phenotype indistinguishable from many other inherited disorders with seizures and weakness are more likely to be diagnosed using genomic testing (see Option 2).

Option 1

When the phenotypic and laboratory findings suggest the diagnosis of MELAS, molecular genetic testing approaches can include serial single-gene testing or use of a multigene panel.

Serial single-gene testing can be considered if (1) mutation of a particular gene accounts for a large proportion of the condition or (2) clinical findings, laboratory findings, ancestry, or other factors indicate that mutation of a particular gene is most likely.

- Typically, blood leukocyte DNA is initially tested for the m.3243A>G pathogenic variant in MT-TL1, which is present in approximately 80% of individuals with typical clinical findings.

- If this is normal, targeted testing for the pathogenic variants m.3271T>C and m.3252A>G in MT-TL1 and m.13513G>A in MT-ND5 is considered next.

A multigene panel that includes MT-TL1, MT-ND5, and other mtDNA genes of interest (see Table 1 and Differential Diagnosis) may also be considered. Note: (1) The genes included and the sensitivity of multigene panels vary by laboratory and are likely to change over time. (2) Some multigene panels may include genes not associated with the condition discussed in this GeneReview; thus, clinicians need to determine which multigene panel is most likely to identify the genetic cause of the condition at the most reasonable cost while limiting identification of variants of uncertain significance and pathogenic variants in genes that do not explain the underlying phenotype. (3) In some laboratories, panel options may include a custom laboratory-designed panel and/or custom phenotype-focused exome analysis that includes genes specified by the clinician. (4) Methods used in a panel may include sequence analysis, deletion/duplication analysis, and/or other non-sequencing-based tests.

Entire mitochondrial genome sequencing that includes MT-TL1, MT-ND5, and other mtDNA genes of interest (see Table 1 and Differential Diagnosis) is most likely to identify the genetic cause of the condition at the most reasonable cost while limiting identification of variants of uncertain significance and pathogenic variants in genes that do not explain the underlying phenotype.

For an introduction to multigene panels click here. More detailed information for clinicians ordering genetic tests can be found here.

Option 2

When the phenotype is indistinguishable from many other inherited disorders characterized by seizures and weakness, comprehensive genomic testing (which does not require the clinician to determine which gene[s] are likely involved) is the best option. Exome sequencing is most commonly used; genome sequencing is also possible. Many laboratories require that the clinician specify if the mitochondrial genome should be included as part of the comprehensive genomic testing.

For an introduction to comprehensive genomic testing click here. More detailed information for clinicians ordering genomic testing can be found here.

Table 1.

Genetic Causes of MELAS

| Gene 1, 2 | % of MELAS Attributed to Pathogenic Variants in This Gene | Proportion of Pathogenic Variants 3 Detectable by Sequence Analysis 4 |

|---|---|---|

| MT-TL1 | >80% | 100% |

| MT-ND5 | <10% | 100% |

| MT-TC MT-TF MT-TH MT-TK MT-TL2 MT-TQ MT-TV MT-TW MT-TS1 MT-TS2 MT-ND1 MT-ND6 MT-CO2 MT-CO3 MT-CYB | Rare | 100% |

Pathogenic variants of any one of the genes included in this table account for >1% of MELAS.

- 1.

Genes are listed from most frequent to least frequent genetic cause of MELAS.

- 2.

See Table A. Genes and Databases for chromosome locus and protein.

- 3.

See Molecular Genetics for information on pathogenic allelic variants detected.

- 4.

Sequence analysis detects variants that are benign, likely benign, of uncertain significance, likely pathogenic, or pathogenic. Pathogenic variants may include small intragenic deletions/insertions and missense, nonsense, and splice site variants; typically, exon or whole-gene deletions/duplications are not detected. For issues to consider in interpretation of sequence analysis results, click here.

Clinical Characteristics

Clinical Description

MELAS is a multisystem disorder with protean manifestations. The vast majority of affected individuals develop signs and symptoms of MELAS between ages two and 40 years. Childhood is the typical age of onset with 65%-76% of affected individuals presenting at or before age 20 years. Onset of symptoms before age two years or after age 40 years is uncommon (age<2 years: 5%-8% of individuals; age >40 years: 1%-6% of individuals).

Individuals with MELAS frequently present with more than one initial clinical manifestation. The most common initial symptoms are seizures, recurrent headaches, stroke-like episodes, cortical vision loss, muscle weakness, recurrent vomiting, and short stature (Table 2). Table 3 summarizes the clinical manifestations of MELAS organized according to their prevalence [Hirano & Pavlakis 1994, Sproule & Kaufmann 2008, Yatsuga et al 2012, El-Hattab et al 2015].

Table 2.

MELAS: Initial Clinical Manifestations

| Frequency | Manifestations |

|---|---|

| ≥25% |

|

| 10%-24% |

|

| <10% |

|

Table 3.

MELAS: Additional Clinical Manifestations

| Frequency | Manifestations |

|---|---|

| ≥90% |

|

| 7%-89% |

|

| 50%-74% |

|

| 25%-49% |

|

| <25% |

|

Neurologic manifestations

- Stroke-like episodes present clinically with partially reversible aphasia, cortical vision loss, motor weakness, headaches, altered mental status, and seizures with the eventual progressive accumulation of neurologic deficits.

- Dementia affects intelligence, language, perception, attention, and memory function.

- Both the underlying neurologic dysfunction and the accumulating cortical injuries due to stroke-like episodes contribute to dementia.

- Executive function deficits have been observed despite the relative sparing of the frontal lobe on neuroimaging, indicating an additional diffuse neurodegenerative process in addition to the damage caused by the stroke-like episodes [Sproule & Kaufmann 2008].

- Epilepsy

- Focal and primary generalized seizures can occur.

- Primary generalized seizures in MELAS can occur in the context of normal neuroimaging or be accompanied by neuroimaging abnormalities including stroke-like episodes, white matter lesions, cortical atrophy, and corpus callosum agenesis or hypogenesis (see Suggestive Findings, Brain Imaging).

- Seizures can occur in MELAS as a manifestation of a stroke-like episode or independently, and may even induce a stroke-like episode [Finsterer & Zarrouk-Mahjoub 2015].

- Migrainous headaches in the form of recurrent attacks of severe pulsatile headaches with frequent vomiting are typical in individuals with MELAS and can precipitate stroke-like episodes. These headache episodes are often more severe during the stroke-like episodes [Ohno et al 1997].

- Hearing impairment due to sensorineural hearing loss is usually mild, insidiously progressive, and often an early clinical manifestation [Sproule & Kaufmann 2008].

- Peripheral neuropathy is usually a chronic and progressive, sensorimotor, and distal polyneuropathy. Nerve conduction studies typically show an axonal or mixed axonal and demyelinating neuropathy [Kaufmann et al 2006b].

- Early psychomotor development is usually normal, although developmental delay can occasionally occur.

- Psychiatric illnesses including depression, bipolar disorder, anxiety, psychosis, and personality changes can occur in MELAS [Anglin et al 2012].

Myopathy presents clinically as muscle weakness and exercise intolerance.

Cardiac manifestations

- Both dilated and hypertrophic cardiomyopathy have been observed, however, the more typical is a non-obstructive concentric hypertrophy [Sproule & Kaufmann 2008].

- Cardiac conduction abnormalities including Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome has been reported occasionally [Sproule et al 2007].

Gastrointestinal manifestations. Recurrent or cyclic vomiting is common. Other manifestations include diarrhea, constipation, gastric dysmotility, intestinal pseudo-obstruction, recurrent pancreatitis, and failure to thrive [Fujii et al 2004].

Endocrine manifestations

- Diabetes mellitus occurs occasionally, with an average age of onset of 38 years. Diabetes can be type 1 or type 2. Individuals with type 2 diabetes can initially be treated with diet or sulfonylurea, although significant insulinopenia can develop and affected individuals may require insulin therapy (see Management) [Maassen et al 2004].

- Short stature. Individuals with MELAS syndrome are typically shorter than their unaffected family members. Growth hormone deficiency has occasionally been reported [Yorifuji et al 1996].

- Hypothyroidism, hypogonadotropic hypogonadism, and hypoparathyroidism are infrequent manifestations [El-Hattab et al 2015].

Other manifestations

- Renal manifestations that may include Fanconi proximal tubulopathy, proteinuria, and focal segmental glomerulosclerosis [Hotta et al 2001]

- Pulmonary hypertension [Sproule et al 2008]

- Dermatologic manifestations that may include vitiligo, diffuse erythema with reticular pigmentation, and hypertrichosis [Kubota et al 1999]

- Chronic anemia [Finsterer 2011]

Natural history and life expectancy. The disease progresses over years with episodic deterioration related to stroke-like events. The course varies from individual to individual.

- In a cohort of 33 adults with the pathogenic m.3243A>G variant in MT-TL1 who were followed for three years, deterioration of sensorineural function, cardiac left-ventricular hypertrophy, EEG abnormalities, and overall severity were observed [Majamaa-Voltti et al 2006].

- In a natural history study of 31 individuals with MELAS and 54 symptomatic and asymptomatic obligate carrier relatives over a follow-up period of up to 10.6 years, neurologic examination, neuropsychological testing, and daily living scores significantly declined in all affected individuals with MELAS, whereas no significant deterioration occurred in carrier relatives.

- The death rate was more than 17-fold higher in fully symptomatic individuals compared to carrier relatives. The average observed age at death in the affected MELAS group was 34.5±19 years (range 10.2-81.8 years). Of the deaths, 22% occurred in those younger than 18 years.

- The estimated overall median survival time based on fully symptomatic individuals was 16.9 years from onset of focal neurologic disease [Kaufmann et al 2011].

- A Japanese prospective cohort study of 96 individuals with MELAS confirmed a rapidly progressive course within a five-year interval, with 20.8% of affected individuals dying within a median time of 7.3 years from diagnosis [Yatsuga et al 2012].

Causes of Phenotypic Variability

For all mtDNA pathogenic variants, clinical expression depends on three factors:

- Heteroplasmy. The presence of a mixture of mutated and normal mtDNA

- Tissue distribution of mutated mtDNA

- Threshold effect. The vulnerability of each tissue to impaired oxidative metabolism

While the tissue vulnerability threshold probably does not vary substantially among individuals, mutational load and tissue distribution do vary and may account for the clinical diversity seen in individuals with MELAS. Correlations between the frequency of the more common clinical features and the level of mutated mtDNA in muscle, but not in leukocytes, have been observed [Chinnery et al 1997, Jeppesen et al 2006]. As-yet-undefined nuclear DNA factors may also modify the phenotypic expression of mtDNA pathogenic variants [Moraes et al 1993].

The m.3243A>G pathogenic variant, the most frequent variant associated with MELAS, is associated with diverse clinical manifestations (i.e., progressive external ophthalmoplegia, diabetes mellitus, cardiomyopathy, deafness) that collectively constitute a wide spectrum ranging from MELAS at the severe end to asymptomatic carrier status. More severe phenotypes may be the result of a higher abundance of the pathogenic variant in affected organs [El-Hattab et al 2015].

Genotype-Phenotype Correlations

No clear genotype-phenotype correlations have been identified (see Causes of Phenotypic Variability).

Penetrance

In mtDNA-related disorders, penetrance typically depends on mutational load and tissue distribution, which show random variation within families (see Causes of Phenotypic Variability).

Nomenclature

Typically designated by the acronym MELAS, this disorder may also be referred to as mitochondrial myopathy, encephalopathy, lactic acidosis, and stroke-like episodes.

Prevalence

The prevalence of MELAS has been estimated to be 0.2:100,000 in Japan [Yatsuga et al 2012]. The prevalence of the m.3243A>G pathogenic variant was estimated to be 16:100,000–18:100,000 in Finland [Majamaa et al 1998, Uusimaa et al 2007]. An Australian study found a higher prevalence of the m.3243A>G pathogenic variant: 236:100,000 [Manwaring et al 2007].

Differential Diagnosis

Clinical manifestations of MELAS can be seen in a wide variety of mitochondrial diseases (see Mitochondrial Disorders Overview).

The differential diagnosis of acute stroke includes other causes of stroke in a young person: heart disease, carotid or vertebral diseases, sickle cell disease, vasculopathies, lipoprotein dyscrasias, venous thrombosis, moyamoya disease, complicated migraine (see Familial Hemiplegic Migraine), Fabry disease, and homocystinuria caused by cystathionine beta-synthase deficiency [Meschia & Worrall 2004, Meschia et al 2005]. Besides appropriate specific tests, a maternal history of other problems suggesting mitochondrial dysfunction (short stature, migraine, hearing loss, diabetes mellitus) can help orient the clinician toward the correct diagnosis.

A MELAS-like phenotype with defects in nuclear genes including MRM2 [Garone et al 2017], FASTKD2 [Yoo et al 2017], and POLG [Cheldi et al 2013] has been reported.

Management

Evaluations Following Initial Diagnosis

To establish the extent of disease and needs in an individual diagnosed with MELAS, the evaluations summarized in this section (if not performed as part of the evaluation that led to the diagnosis) are recommended:

Table 5.

Recommended Evaluations Following Initial Diagnosis in Individuals with MELAS

| System/Concern | Evaluation | Comment |

|---|---|---|

| Growth | Measurement of height & weight | |

| Eyes | Ophthalmology eval | To screen for ptosis, optic atrophy, pigmentary retinopathy, ophthalmoplegia, vision deficits |

| Ears | Audiology eval | To detect hearing loss |

| Cardiovascular | Echocardiogram | To screen for cardiomyopathy 1 |

| Electrocardiogram | To evaluate for conduction abnormalities 1 | |

| Renal | Urinalysis & urine amino acid analysis | To evaluate for renal tubulopathy |

| Musculoskeletal | PT/OT assessment | For individuals w/neurologic deficits |

| Neurologic | Neurologic eval | To assess for neurologic deficits 2 |

| Head MRI w/MRS | To evaluate for pathologic changes at baseline | |

| EEG | If seizures are suspected | |

| Neuropsychiatric testing | To assess cognitive abilities & for evidence of dementia | |

| Endocrinologic | Fasting serum glucose | To screen for diabetes mellitus 3 |

| Glucose tolerance test | ||

| Other | Consultation w/clinical geneticist &/or genetic counselor |

OT = occupational therapy; PT = physical therapy

- 1.

Consider referral to a cardiologist.

- 2.

Consider referral to a neurologist.

- 3.

Consider referral to an endocrinologist.

Treatment of Manifestations

Treatment for MELAS is primarily supportive.

Arginine therapy. Recommendations for the management of stroke-like episodes in MELAS with arginine have been published. During the acute stroke-like episode, it is recommended to give a bolus of intravenous arginine (500 mg/kg for children or 10 g/m2 body surface area for adults) within three hours of symptom onset followed by the administration of a similar dosage of intravenous arginine as a continuous infusion over 24 hours for the next three to five days. Once an individual with MELAS has the first stroke-like episode, arginine should be administered prophylactically to reduce the risk of recurrent stroke-like episodes (see Prevention of Primary Manifestations).

Table 6.

Treatment of Manifestations in Individuals with MELAS

| Manifestation/Concern | Treatment | Considerations/Other |

|---|---|---|

| Overall disease process | CoQ10

| May benefit some individuals 1 |

L-carnitine

| ||

Creatine

| ||

| Ptosis | Standard therapy | Eyelid "crutches," blepharoplasty, or frontalis muscle-eyelid implantation could be considered. |

| Sensorineural hearing loss | Standard therapy | Cochlear implantation successful in some 2 |