Encephalitis

Encephalitis is inflammation of the brain. The severity can be variable with symptoms including headache, fever, confusion, a stiff neck, and vomiting. Complications may include seizures, hallucinations, trouble speaking, memory problems, and problems with hearing.

Causes of encephalitis include viruses such as herpes simplex virus and rabies as well as bacteria, fungi, or parasites. Other causes include autoimmune diseases and certain medications. In many cases the cause remains unknown. Risk factors include a weak immune system. Diagnosis is typically based on symptoms and supported by blood tests, medical imaging, and analysis of cerebrospinal fluid.

Certain types are preventable with vaccines. Treatment may include antiviral medications (such as acyclovir), anticonvulsants, and corticosteroids. Treatment generally takes place in hospital. Some people require artificial respiration. Once the immediate problem is under control, rehabilitation may be required. In 2015, encephalitis was estimated to have affected 4.3 million people and resulted in 150,000 deaths worldwide.

Signs and symptoms

Adults with encephalitis present with acute onset of fever, headache, confusion, and sometimes seizures. Younger children or infants may present with irritability, poor appetite and fever. Neurological examinations usually reveal a drowsy or confused person. Stiff neck, due to the irritation of the meninges covering the brain, indicates that the patient has either meningitis or meningoencephalitis.

Cause

Viral

Viral encephalitis can occur either as a direct effect of an acute infection, or as one of the sequelae of a latent infection. The majority of viral cases of encephalitis have an unknown cause, however the most common identifiable cause of viral encephalitis is from herpes simplex infection. Other causes of acute viral encephalitis are rabies virus, poliovirus, and measles virus.

Additional possible viral causes are arboviral flavivirus (St. Louis encephalitis, West Nile virus), bunyavirus (La Crosse strain), arenavirus (lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus), reovirus (Colorado tick virus), and henipavirus infections. The Powassan virus is a rare cause of encephalitis.

Bacterial and other

It can be caused by a bacterial infection, such as bacterial meningitis, or may be a complication of a current infectious disease syphilis (secondary encephalitis).

Certain parasitic or protozoal infestations, such as toxoplasmosis, malaria, or primary amoebic meningoencephalitis, can also cause encephalitis in people with compromised immune systems. Lyme disease or Bartonella henselae may also cause encephalitis.

Other bacterial pathogens, like Mycoplasma and those causing rickettsial disease, cause inflammation of the meninges and consequently encephalitis. A non-infectious cause includes acute disseminated encephalitis which is demyelinated.

Limbic encephalitis

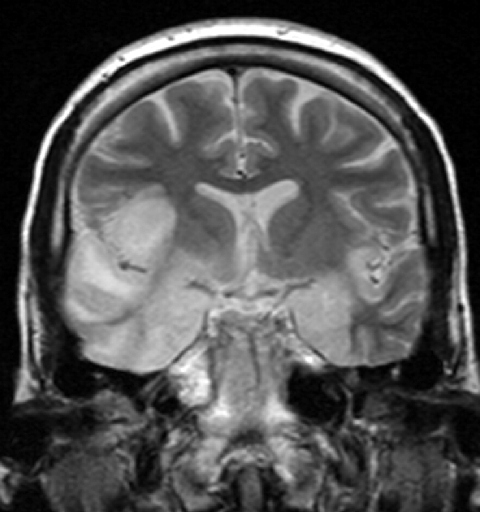

Limbic encephalitis refers to inflammatory disease confined to the limbic system of the brain. The clinical presentation often includes disorientation, disinhibition, memory loss, seizures, and behavioral anomalies. MRI imaging reveals T2 hyperintensity in the structures of the medial temporal lobes, and in some cases, other limbic structures. Some cases of limbic encephalitis are of autoimmune origin.

Autoimmune encephalitis

Autoimmune encephalitis signs can include catatonia, psychosis, abnormal movements, and autonomic dysregulation. Antibody-mediated anti-N-methyl-D-aspartate-receptor encephalitis and Rasmussen encephalitis are examples of autoimmune encephalitis. Anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis is the most common autoimmune form, and is accompanied by ovarian teratoma in 58 percent of affected women 18–45 years of age.

Encephalitis lethargica

Encephalitis lethargica is identified by high fever, headache, delayed physical response, and lethargy. Individuals can exhibit upper body weakness, muscular pains, and tremors, though the cause of encephalitis lethargica is not currently known. From 1917 to 1928, an epidemic of encephalitis lethargica occurred worldwide.

Diagnosis

People should only be diagnosed with encephalitis if they have a decreased or altered level of consciousness, lethargy, or personality change for at least twenty-four hours without any other explainable cause. Diagnosing encephalitis is done via a variety of tests:

- Brain scan, done by MRI, can determine inflammation and differentiate from other possible causes.

- EEG, in monitoring brain activity, encephalitis will produce abnormal signal.

- Lumbar puncture (spinal tap), this helps determine via a test using the cerebral-spinal fluid, obtained from the lumbar region.

- Blood test

- Urine analysis

- Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing of the cerebrospinal fluid, to detect the presence of viral DNA which is a sign of viral encephalitis.

Prevention

Vaccination is available against tick-borne and Japanese encephalitis and should be considered for at-risk individuals. Post-infectious encephalomyelitis complicating smallpox vaccination is avoidable, for all intents and purposes, as smallpox is nearly eradicated. Contraindication to Pertussis immunization should be observed in patients with encephalitis.

Treatment

Treatment (which is based on supportive care) is as follows:

- Antiviral medications (if virus is cause)

- Antibiotics, (if bacteria is cause)

- Steroids are used to reduce brain swelling

- Sedatives for restlessness

- Acetaminophen for fever

- Occupational and physical therapy (if brain is affected post-infection)

Pyrimethamine-based maintenance therapy is often used to treat Toxoplasmic Encephalitis (TE), which is caused by Toxoplasma gondii and can be life-threatening for people with weak immune systems. The use of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART), in conjunction with the established pyrimethamine-based maintenance therapy, decreases the chance of relapse in patients with HIV and TE from approximately 18% to 11%. This is a significant difference as relapse may impact the severity and prognosis of disease and result in an increase in healthcare expenditure.

The effectiveness of intravenous immunoglobulin for the management of childhood encephalitis is unclear. Systematic reviews have been unable to draw firm conclusions because of a lack of randomised double-blind studies with sufficient numbers of patients and sufficient follow-up. There is the possibility of a benefit of intravenous immunoglobulin for some forms of childhood encephalitis on some indicators such as length of hospital stay, time to stop spasms, time to regain consciousness, and time to resolution of neuropathic symptoms and fever. Intravenous immunoglobulin for Japanese Encephalitis appeared to have no benefit when compared with placebo (pretend) treatment.

Prognosis

Identification of poor prognostic factors include cerebral edema, status epilepticus, and thrombocytopenia. In contrast, a normal encephalogram at the early stages of diagnosis is associated with high rates of survival.

Epidemiology

The number of new cases a year of acute encephalitis in Western countries is 7.4 cases per 100,000 people per year. In tropical countries, the incidence is 6.34 per 100,000 people per year. The number of cases of encephalitis has not changed much over time, with about 250,000 cases a year from 2005 to 2015 in the US. Approximately seven per 100,000 people were hospitalized for encephalitis in the US during this time. In 2015, encephalitis was estimated to have affected 4.3 million people and resulted in 150,000 deaths worldwide. Herpes simplex encephalitis has an incidence of 2–4 per million of the population per year.

Terminology

Encephalitis with meningitis is known as meningoencephalitis, while encephalitis with involvement of the spinal cord is known as encephalomyelitis.

The word is from Ancient Greek ἐγκέφαλος, enképhalos "brain", composed of ἐν, en, "in" and κεφαλή, kephalé, "head", and the medical suffix -itis "inflammation".

See also

- Bickerstaff's encephalitis

- Cerebritis

- La Crosse encephalitis

- Primary amoebic meningoencephalitis

- Wernicke's encephalopathy

- World Encephalitis Day

- Zika virus