Sarcoidosis

Sarcoidosis is a disease involving abnormal collections of inflammatory cells that form lumps known as granulomata. The disease usually begins in the lungs, skin, or lymph nodes. Less commonly affected are the eyes, liver, heart, and brain. Any organ, however, can be affected. The signs and symptoms depend on the organ involved. Often, no, or only mild, symptoms are seen. When it affects the lungs, wheezing, coughing, shortness of breath, or chest pain may occur. Some may have Löfgren syndrome with fever, large lymph nodes, arthritis, and a rash known as erythema nodosum.

The cause of sarcoidosis is unknown. Some believe it may be due to an immune reaction to a trigger such as an infection or chemicals in those who are genetically predisposed. Those with affected family members are at greater risk. Diagnosis is partly based on signs and symptoms, which may be supported by biopsy. Findings that make it likely include large lymph nodes at the root of the lung on both sides, high blood calcium with a normal parathyroid hormone level, or elevated levels of angiotensin-converting enzyme in the blood. The diagnosis should only be made after excluding other possible causes of similar symptoms such as tuberculosis.

Sarcoidosis may resolve without any treatment within a few years. However, some people may have long-term or severe disease. Some symptoms may be improved with the use of anti-inflammatory drugs such as ibuprofen. In cases where the condition causes significant health problems, steroids such as prednisone are indicated. Medications such as methotrexate, chloroquine, or azathioprine may occasionally be used in an effort to decrease the side effects of steroids. The risk of death is 1–7%. The chance of the disease returning in someone who has had it previously is less than 5%.

In 2015, pulmonary sarcoidosis and interstitial lung disease affected 1.9 million people globally and they resulted in 122,000 deaths. It is most common in Scandinavians, but occurs in all parts of the world. In the United States, risk is greater among black people as opposed to white people. It usually begins between the ages of 20 and 50. It occurs more often in women than men. Sarcoidosis was first described in 1877 by the English doctor Jonathan Hutchinson as a non-painful skin disease.

Signs and symptoms

Sarcoidosis is a systemic inflammatory disease that can affect any organ, although it can be asymptomatic and is discovered by accident in about 5% of cases. Common symptoms, which tend to be vague, include fatigue (unrelieved by sleep; occurs in 66% of cases), lack of energy, weight loss, joint aches and pains (which occur in about 70% of cases), arthritis (14–38% of cases), dry eyes, swelling of the knees, blurry vision, shortness of breath, a dry, hacking cough, or skin lesions. Less commonly, people may cough up blood. The cutaneous symptoms vary, and range from rashes and noduli (small bumps) to erythema nodosum, granuloma annulare, or lupus pernio. Sarcoidosis and cancer may mimic one another, making the distinction difficult.

The combination of erythema nodosum, bilateral hilar lymphadenopathy, and joint pain is called Löfgren syndrome, which has a relatively good prognosis. This form of the disease occurs significantly more often in Scandinavian patients than in those of non-Scandinavian origin.

Respiratory tract

Localization to the lungs is by far the most common manifestation of sarcoidosis. At least 90% of those affected experience lung involvement. Overall, about 50% develop permanent pulmonary abnormalities, and 5 to 15% have progressive fibrosis of the lung parenchyma. Sarcoidosis of the lung is primarily an interstitial lung disease in which the inflammatory process involves the alveoli, small bronchi, and small blood vessels. In acute and subacute cases, physical examination usually reveals dry crackles. At least 5% of cases include pulmonary arterial hypertension. The upper respiratory tract (including the larynx, pharynx, and sinuses) may be affected, which occurs in between 5 and 10% of cases.

The four stages of pulmonary involvement are based on radiological stage of the disease, which is helpful in prognosis:

- Stage I: bilateral hilar lymphadenopathy (BHL) alone

- Stage II: BHL with pulmonary infiltrates

- Stage III: pulmonary infiltrates without BHL

- Stage IV: fibrosis

Use of the Scadding scale only provides general information regarding the prognosis of the pulmonary disease over time. Caution is recommended, as it only shows a general relation with physiological markers of the disease and the variation is such that it has limited applicability in individual assessments, including treatment decisions.

Skin

Sarcoidosis involves the skin in between 9 and 37% of cases and is more common in African Americans than in European Americans. The skin is the second-most commonly affected organ after the lungs. The most common lesions are erythema nodosum, plaques, maculopapular eruptions, subcutaneous nodules, and lupus pernio. Treatment is not required, since the lesions usually resolve spontaneously in 2–4 weeks. Although it may be disfiguring, cutaneous sarcoidosis rarely causes major problems. Sarcoidosis of the scalp presents with diffuse or patchy hair loss.

Heart

Histologically, sarcoidosis of the heart is an active granulomatous inflammation surrounded by reactive oedema. The distribution of affected areas is patchy with localised enlargement of heart muscles. This causes scarring and remodelling of the heart, which leads to dilatation of heart cavities and thinning of heart muscles. As the situation progresses, it leads to aneurysm of heart chambers. When the distribution is diffuse, there would be dilatation of both ventricles of the heart, causing heart failure and arrhythmia. When the conduction system in the intraventricular septum is affected, it would lead to heart block, ventricular tachycardia and ventricular arrhythmia, causing sudden death. Nevertheless, the involvement of pericardium and heart valves are uncommon.

The frequency of cardiac involvement varies and is significantly influenced by race; in Japan, more than 25% of those with sarcoidosis have symptomatic cardiac involvement, whereas in the US and Europe, only about 5% of cases present with cardiac involvement. Autopsy studies in the US have revealed a frequency of cardiac involvement of about 20–30%, whereas autopsy studies in Japan have shown a frequency of 60%. The presentation of cardiac sarcoidosis can range from asymptomatic conduction abnormalities to fatal ventricular arrhythmia.

Conduction abnormalities are the most common cardiac manifestations of sarcoidosis in humans and can include complete heart block. Second to conduction abnormalities, in frequency, are ventricular arrhythmias, which occurs in about 23% of case with cardiac involvement. Sudden cardiac death, either due to ventricular arrhythmias or complete heart block is a rare complication of cardiac sarcoidosis. Cardiac sarcoidosis can cause fibrosis, granuloma formation, or the accumulation of fluid in the interstitium of the heart, or a combination of the former two. Cardiac sarcoidosis may also cause congestive heart failure when granulomas cause myocardial fibrosis and scarring. Congestive heart failure affects 25-75% of those with cardiac sarcoidosis. Pulmonary arterial hypertension occurs by two mechanisms in cardiac sarcoidosis: reduced left heart function due to granulomas weakening the heart muscle or from impaired blood flow.

Eye

Eye involvement occurs in about 10–90% of cases. Manifestations in the eye include uveitis, uveoparotitis, and retinal inflammation, which may result in loss of visual acuity or blindness. The most common ophthalmologic manifestation of sarcoidosis is uveitis. The combination of anterior uveitis, parotitis, VII cranial nerve paralysis and fever is called uveoparotid fever or Heerfordt syndrome (D86.8). Development of scleral nodule associated with sarcoidosis has been observed.

Nervous system

Any of the components of the nervous system can be involved. Sarcoidosis affecting the nervous system is known as neurosarcoidosis. Cranial nerves are most commonly affected, accounting for about 5–30% of neurosarcoidosis cases, and peripheral facial nerve palsy, often bilateral, is the most common neurological manifestation of sarcoidosis. It occurs suddenly and is usually transient. The central nervous system involvement is present in 10–25% of sarcoidosis cases. Other common manifestations of neurosarcoidosis include optic nerve dysfunction, papilledema, palate dysfunction, neuroendocrine changes, hearing abnormalities, hypothalamic and pituitary abnormalities, chronic meningitis, and peripheral neuropathy. Myelopathy, that is spinal cord involvement, occurs in about 16–43% of neurosarcoidosis cases and is often associated with the poorest prognosis of the neurosarcoidosis subtypes. Whereas facial nerve palsies and acute meningitis due to sarcoidosis tend to have the most favourable prognosis, another common finding in sarcoidosis with neurological involvement is autonomic or sensory small-fiber neuropathy. Neuroendocrine sarcoidosis accounts for about 5–10% of neurosarcoidosis cases and can lead to diabetes insipidus, changes in menstrual cycle and hypothalamic dysfunction. The latter can lead to changes in body temperature, mood, and prolactin (see the endocrine and exocrine section for details).

Endocrine and exocrine

Prolactin is frequently increased in sarcoidosis, between 3 and 32% of cases have hyperprolactinemia this frequently leads to amenorrhea, galactorrhea, or nonpuerperal mastitis in women. It also frequently causes an increase in 1,25-dihydroxy vitamin D, the active metabolite of vitamin D, which is usually hydroxylated within the kidney, but in sarcoidosis patients, hydroxylation of vitamin D can occur outside the kidneys, namely inside the immune cells found in the granulomas the condition produces. 1,25-dihydroxy vitamin D is the main cause for hypercalcemia in sarcoidosis and is overproduced by sarcoid granulomata. Gamma-interferon produced by activated lymphocytes and macrophages plays a major role in the synthesis of 1 alpha, 25(OH)2D3. Hypercalciuria (excessive secretion of calcium in one's urine) and hypercalcemia (an excessively high amount of calcium in the blood) are seen in <10% of individuals and likely results from the increased 1,25-dihydroxy vitamin D production.

Thyroid dysfunction is seen in 4.2–4.6% of cases.

Parotid enlargement occurs in about 5–10% of cases. Bilateral involvement is the rule. The gland is usually not tender, but firm and smooth. Dry mouth can occur; other exocrine glands are affected only rarely. The eyes, their glands, or the parotid glands are affected in 20–50% of cases.

Gastrointestinal and genitourinary

Symptomatic gastrointestinal (GI) involvement occurs in less than 1% of cases (if one excludes the liver), and most commonly the stomach is affected, although the small or large intestine may also be affected in a small portion of cases. Studies at autopsy have revealed GI involvement in less than 10% of people. These cases would likely mimic Crohn's disease, which is a more commonly intestine-affecting granulomatous disease. About 1–3% of people have evidence of pancreatic involvement at autopsy. Symptomatic kidney involvement occurs in just 0.7% of cases, although evidence of kidney involvement at autopsy has been reported in up to 22% of people and occurs exclusively in cases of chronic disease. Symptomatic kidney involvement is usually nephrocalcinosis, although granulomatous interstitial nephritis that presents with reduced creatinine clearance and little proteinuria is a close second. Less commonly, the epididymis, testicles, prostate, ovaries, fallopian tubes, uterus, or the vulva may be affected, the latter may cause vulva itchiness. Testicular involvement has been reported in about 5% of people at autopsy. In males, sarcoidosis may lead to infertility.

Around 70% of people have granulomas in their livers, although only in about 20–30% of cases, liver function test anomalies reflecting this fact are seen. About 5–15% of sufferers exhibit hepatomegaly. Only 5–30% of cases of liver involvement are symptomatic. Usually, these changes reflect a cholestatic pattern and include raised levels of alkaline phosphatase (which is the most common liver function test anomaly seen in those with sarcoidosis), while bilirubin and aminotransferases are only mildly elevated. Jaundice is rare.

Blood

Abnormal blood tests are frequent, accounting for over 50% of cases, but are not diagnostic. Lymphopenia is the most common blood anomaly in sarcoidosis. Anemia occurs in about 20% of people with sarcoidosis. Leukopenia is less common and occurs in even fewer cases but is rarely severe. Thrombocytopenia and hemolytic anemia are fairly rare. In the absence of splenomegaly, leukopenia may reflect bone marrow involvement, but the most common mechanism is a redistribution of blood T cells to sites of disease. Other nonspecific findings include monocytosis, occurring in the majority of sarcoidosis cases, increased hepatic enzymes or alkaline phosphatase. People with sarcoidosis often have immunologic anomalies like allergies to test antigens such as Candida or purified protein derivative. Polyclonal hypergammaglobulinemia is also a fairly common immunologic anomaly seen in sarcoidosis.

Lymphadenopathy (swollen glands) is common in sarcoidosis and occurs in 15% of cases. Intrathoracic nodes are enlarged in 75 to 90% of all people; usually this involves the hilar nodes, but the paratracheal nodes are commonly involved. Peripheral lymphadenopathy is very common, particularly involving the cervical (the most common head and neck manifestation of the disease), axillary, epitrochlear, and inguinal nodes. Approximately 75% of cases show microscopic involvement of the spleen, although only in about 5–10% of cases does splenomegaly appear.

Bone, joints, and muscles

Sarcoidosis can be involved with the joints, bones, and muscles. This causes a wide variety of musculoskeletal complaints that act through different mechanisms. About 5–15% of cases affect the bones, joints, or muscles.

Arthritic syndromes can be categorized as acute or chronic. Sarcoidosis patients suffering acute arthritis often also have bilateral hilar lymphadenopathy and erythema nodosum. These three associated syndromes often occur together in Löfgren syndrome. The arthritis symptoms of Löfgren syndrome occur most frequently in the ankles, followed by the knees, wrists, elbows, and metacarpophalangeal joints. Usually, true arthritis is not present, but instead, periarthritis appears as a swelling in the soft tissue around the joints that can be seen by ultrasonographic methods. These joint symptoms tend to precede or occur at the same time as erythema nodosum develops. Even when erythema nodosum is absent, it is believed that the combination of hilar lymphadenopathy and ankle periarthritis can be considered as a variant of Löfgren syndrome. Enthesitis also occurs in about one-third of patients with acute sarcoid arthritis, mainly affecting the Achilles tendon and heels. Soft-tissue swelling of the ankles can be prominent, and biopsy of this soft tissue reveals no granulomas, but does show panniculitis similar to erythema nodosum.

Chronic sarcoid arthritis usually occurs in the setting of more diffuse organ involvement. The ankles, knees, wrists, elbows, and hands may all be affected in the chronic form and often this presents itself in a polyarticular pattern. Dactylitis similar to that seen in psoriatic arthritis, that is associated with pain, swelling, overlying skin erythema, and underlying bony changes may also occur. Development of Jaccoud arthropathy (a nonerosive deformity) is very rarely seen.

Bone involvement in sarcoidosis has been reported in 1–13% of cases. The most frequent sites of involvement are the hands and feet, whereas the spine is less commonly affected. Half of the patients with bony lesions experience pain and stiffness, whereas the other half remain asymptomatic. Periostitis is rarely seen in sarcoidosis and has been found to present itself at the femoral bone.

Cause

The exact cause of sarcoidosis is not known. The current working hypothesis is, in genetically susceptible individuals, sarcoidosis is caused through alteration to the immune response after exposure to an environmental, occupational, or infectious agent. Some cases may be caused by treatment with tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitors like etanercept.

Genetics

The heritability of sarcoidosis varies according to ethnicity. About 20% of African Americans with sarcoidosis have a family member with the condition, whereas the same figure for European Americans is about 5%. Additionally, in African Americans, who seem to experience more severe and chronic disease, siblings and parents of sarcoidosis cases have about a 2.5-fold increased risk for developing the disease. In Swedish individuals heritability was found to be 39%. In this group, if a first-degree family member was affected, a person has a four-fold greater risk of being affected.

Investigations of genetic susceptibility yielded many candidate genes, but only few were confirmed by further investigations and no reliable genetic markers are known. Currently, the most interesting candidate gene is BTNL2; several HLA-DR risk alleles are also being investigated. In persistent sarcoidosis, the HLA haplotype HLA-B7-DR15 is either cooperating in disease or another gene between these two loci is associated. In nonpersistent disease, a strong genetic association exists with HLA DR3-DQ2. Cardiac sarcoid has been connected to tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNFA) variants.

Infectious agents

Several infectious agents appear to be significantly associated with sarcoidosis, but none of the known associations is specific enough to suggest a direct causative role. The major implicated infectious agents include: mycobacteria, fungi, borrelia, and rickettsia. A meta-analysis investigating the role of mycobacteria in sarcoidosis found it was present in 26.4% of cases, but they also detected a possible publication bias, so the results need further confirmation. Mycobacterium tuberculosis catalase-peroxidase has been identified as a possible antigen catalyst of sarcoidosis. The disease has also been reported by transmission via organ transplants. A large epidemiological study found little evidence that infectious diseases spanning years before sarcoidosis diagnosis could confer measurable risks for sarcoidosis diagnosis in the future.

Autoimmune

Association of autoimmune disorders has been frequently observed. The exact mechanism of this relation is not known, but some evidence supports the hypothesis that this is a consequence of Th1 lymphokine prevalence. Tests of delayed cutaneous hypersensitivity have been used to measure progression.

Pathophysiology

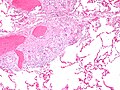

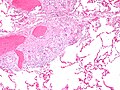

Granulomatous inflammation is characterized primarily by the accumulation of macrophages and activated T-lymphocytes, with increased production of key inflammatory mediators, Tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF), Interferon gamma, Interleukin 2 (IL-2), IL-8, IL-10, IL-12, IL-18, IL-23 and transforming growth factor beta (TGF-β), indicative of a T helper cell-mediated immune response. Sarcoidosis has paradoxical effects on inflammatory processes; it is characterized by increased macrophage and CD4 helper T-cell activation, resulting in accelerated inflammation, but immune response to antigen challenges such as tuberculin is suppressed. This paradoxic state of simultaneous hyper- and hypoactivity is suggestive of a state of anergy. The anergy may also be responsible for the increased risk of infections and cancer.

The regulatory T-lymphocytes in the periphery of sarcoid granulomas appear to suppress IL-2 secretion, which is hypothesized to cause the state of anergy by preventing antigen-specific memory responses. Schaumann bodies seen in sarcoidosis are calcium and protein inclusions inside of Langhans giant cells as part of a granuloma. Sarcoidosis is characterized by the formation of non-caseous epithelioid cell granulomas in various organs and tissues.

While TNF is widely believed to play an important role in the formation of granulomas (this is further supported by the finding that in animal models of mycobacterial granuloma formation inhibition of either TNF or IFN-γ production inhibits granuloma formation), sarcoidosis can and does still develop in those being treated with TNF antagonists like etanercept. B cells also likely play a role in the pathophysiology of sarcoidosis. Serum levels of soluble human leukocyte antigen (HLA) class I antigens and angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) are higher in people with sarcoidosis. Likewise the ratio of CD4/CD8 T cells in bronchoalveolar lavage is usually higher in people with pulmonary sarcoidosis (usually >3.5), although it can be normal or even abnormally low in some cases. Serum ACE levels have been found to usually correlate with total granuloma load.

Cases of sarcoidosis have also been reported as part of the immune reconstitution syndrome of HIV, that is, when people receive treatment for HIV, their immune system rebounds and the result is that it starts to attack the antigens of opportunistic infections caught prior to said rebound and the resulting immune response starts to damage healthy tissue.

Sarcoidosis in a lymph node

Asteroid body in sarcoidosis

Micrograph showing pulmonary sarcoidosis with granulomas with asteroid bodies, H&E stain

Diagnosis

Diagnosis of sarcoidosis is a matter of exclusion, as there is no specific test for the condition. To exclude sarcoidosis in a case presenting with pulmonary symptoms might involve a chest radiograph, CT scan of chest, PET scan, CT-guided biopsy, mediastinoscopy, open lung biopsy, bronchoscopy with biopsy, endobronchial ultrasound, and endoscopic ultrasound with fine-needle aspiration of mediastinal lymph nodes (EBUS FNA). Tissue from biopsy of lymph nodes is subjected to both flow cytometry to rule out cancer and special stains (acid fast bacilli stain and Gömöri methenamine silver stain) to rule out microorganisms and fungi.

Serum markers of sarcoidosis, include: serum amyloid A, soluble interleukin-2 receptor, lysozyme, angiotensin converting enzyme, and the glycoprotein KL-6. Angiotensin-converting enzyme blood levels are used in the monitoring of sarcoidosis. A bronchoalveolar lavage can show an elevated (of at least 3.5) CD4/CD8 T cell ratio, which is indicative (but not proof) of pulmonary sarcoidosis. In at least one study the induced sputum ratio of CD4/CD8 and level of TNF was correlated to those in the lavage fluid. A sarcoidosis-like lung disease called granulomatous–lymphocytic interstitial lung disease can be seen in patients with common variable immunodeficiency (CVID) and therefore serum antibody levels should be measured to exclude CVID.

Differential diagnosis includes metastatic disease, lymphoma, septic emboli, rheumatoid nodules, granulomatosis with polyangiitis, varicella infection, tuberculosis, and atypical infections, such as Mycobacterium avium complex, cytomegalovirus, and cryptococcus. Sarcoidosis is confused most commonly with neoplastic diseases, such as lymphoma, or with disorders characterized also by a mononuclear cell granulomatous inflammatory process, such as the mycobacterial and fungal disorders.

Chest radiograph changes are divided into four stages:

- bihilar lymphadenopathy

- bihilar lymphadenopathy and reticulonodular infiltrates

- bilateral pulmonary infiltrates

- fibrocystic sarcoidosis typically with upward hilar retraction, cystic and bullous changes

Although people with stage 1 radiographs tend to have the acute or subacute, reversible form of the disease, those with stages 2 and 3 often have the chronic, progressive disease; these patterns do not represent consecutive "stages" of sarcoidosis. Thus, except for epidemiologic purposes, this categorization is mostly of historic interest.

In sarcoidosis presenting in the Caucasian population, hilar adenopathy and erythema nodosum are the most common initial symptoms. In this population, a biopsy of the gastrocnemius muscle is a useful tool in correctly diagnosing the person. The presence of a noncaseating epithelioid granuloma in a gastrocnemius specimen is definitive evidence of sarcoidosis, as other tuberculoid and fungal diseases extremely rarely present histologically in this muscle.

Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (CMR) is one modality for diagnosing cardiac sarcoidosis. It has 78% specificity in diagnosing cardiac sarcoidosis. Its T2-weighted imaging can detect acute inflammation. Meanwhile, late gadolinium contrast (LGE) can detect fibrosis or scar. Lesions at the subpericardium and midwall enhancement of basal spetum or inferolateral wall is strongly suggestive of sarcoidosis. MRI can also follow up on the treatment efficacy of corticosteriods and prognosis of cardiac sarcoidosis.

PET scan is able to quantify disease activity which cannot be performed by CMR.

Hilar adenopathy especially on the person's left (AP CXR)

Hilar adenopathy especially on the person's left (lateral CXR)

Hilar adenopathy especially on the person's left (coronal CT)

Hilar adenopathy especially on the person's left (transverse CT)

Classification

Sarcoidosis may be divided into the following types:

- Annular sarcoidosis

- Erythrodermic sarcoidosis

- Ichthyosiform sarcoidosis

- Hypopigmented sarcoidosis

- Löfgren syndrome

- Lupus pernio

- Morpheaform sarcoidosis

- Mucosal sarcoidosis

- Neurosarcoidosis

- Papular sarcoid

- Scar sarcoid

- Subcutaneous sarcoidosis

- Systemic sarcoidosis

- Ulcerative sarcoidosis

Treatment

Treatments for sarcoidosis vary greatly depending on the patient. At least half of patients require no systemic therapy. Most people (>75%) only require symptomatic treatment with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) like ibuprofen or aspirin. For those presenting with lung symptoms, unless the respiratory impairment is devastating, active pulmonary sarcoidosis is observed usually without therapy for two to three months; if the inflammation does not subside spontaneously, therapy is instituted.

Major categories of drug interventions include glucocorticoids, antimetabolites, biologic agents especially monoclonal anti-tumor necrosis factor antibodies. Investigational treatments include specific antibiotic combinations and mesenchymal stem cells. If drug intervention is indicated, a step-wise approach is often used to explore alternatives in order of increasing side effects and to monitor potentially toxic effects.

Corticosteroids, most commonly prednisone or prednisolone, have been the standard treatment for many years. In some people, this treatment can slow or reverse the course of the disease, but other people do not respond to steroid therapy. The use of corticosteroids in mild disease is controversial because in many cases the disease remits spontaneously.

Antimetabolites

Antimetabolites, also categorized as steroid-sparing agents, such as azathioprine, methotrexate, mycophenolic acid, and leflunomide are often used as alternatives to corticosteroids. Of these, methotrexate is most widely used and studied. Methotrexate is considered a first-line treatment in neurosarcoidosis, often in conjunction with corticosteroids. Long-term treatment with methotrexate is associated with liver damage in about 10% of people and hence may be a significant concern in people with liver involvement and requires regular liver function test monitoring. Methotrexate can also lead to pulmonary toxicity (lung damage), although this is fairly uncommon and more commonly it can confound the leukopenia caused by sarcoidosis. Due to these safety concerns it is often recommended that methotrexate is combined with folic acid in order to prevent toxicity. Azathioprine treatment can also lead to liver damage. However, the risk of infection appears to be about 40% lower in those treated with methotrexate instead of azathioprine. Leflunomide is being used as a replacement for methotrexate, possibly due to its purportedly lower rate of pulmonary toxicity. Mycophenolic acid has been used successfully in uveal sarcoidosis, neurosarcoidosis (especially CNS sarcoidosis; minimally effective in sarcoidosis myopathy), and pulmonary sarcoidosis.

Immunosuppressants

As the granulomas are caused by collections of immune system cells, particularly T cells, there has been some success using immunosuppressants (like cyclophosphamide, cladribine, chlorambucil, and cyclosporine), immunomodulatory (pentoxifylline and thalidomide), and anti-tumor necrosis factor treatment (such as infliximab, etanercept, golimumab, and adalimumab).

In a clinical trial cyclosporine added to prednisone treatment failed to demonstrate any significant benefit over prednisone alone in people with pulmonary sarcoidosis, although there was evidence of increased toxicity from the addition of cyclosporine to the steroid treatment including infections, malignancies (cancers), hypertension, and kidney dysfunction. Likewise chlorambucil and cyclophosphamide are seldom used in the treatment of sarcoidosis due to their high degree of toxicity, especially their potential for causing malignancies. Infliximab has been used successfully to treat pulmonary sarcoidosis in clinical trials in a number of cases. Etanercept, on the other hand, has failed to demonstrate any significant efficacy in people with uveal sarcoidosis in a couple of clinical trials. Likewise golimumab has failed to show any benefit in those with pulmonary sarcoidosis. One clinical trial of adalimumab found treatment response in about half of subjects, which is similar to that seen with infliximab, but as adalimumab has better tolerability profile it may be preferred over infliximab.

Specific organ treatments

Ursodeoxycholic acid has been used successfully as a treatment for cases with liver involvement. Thalidomide has also been tried successfully as a treatment for treatment-resistant lupus pernio in a clinical trial, which may stem from its anti-TNF activity, although it failed to exhibit any efficacy in a pulmonary sarcoidosis clinical trial. Cutaneous disease may be successfully managed with antimalarials (such as chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine) and the tetracycline antibiotic, minocycline. Antimalarials have also demonstrated efficacy in treating sarcoidosis-induced hypercalcemia and neurosarcoidosis. Long-term use of antimalarials is limited, however, by their potential to cause irreversible blindness and hence the need for regular ophthalmologic screening. This toxicity is usually less of a problem with hydroxychloroquine than with chloroquine, although hydroxychloroquine can disturb the glucose homeostasis.

Recently selective phosphodiesterase 4 (PDE4) inhibitors like apremilast (a thalidomide derivative), roflumilast, and the less subtype-selective PDE4 inhibitor, pentoxifylline, have been tried as a treatment for sarcoidosis, with successful results being obtained with apremilast in cutaneous sarcoidosis in a small open-label study. Pentoxifylline has been used successfully to treat acute disease although its use is greatly limited by its gastrointestinal toxicity (mostly nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea). Case reports have supported the efficacy of rituximab, an anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody and a clinical trial investigating atorvastatin as a treatment for sarcoidosis is under-way. ACE inhibitors have been reported to cause remission in cutaneous sarcoidosis and improvement in pulmonary sarcoidosis, including improvement in pulmonary function, remodeling of lung parenchyma and prevention of pulmonary fibrosis in separate case series'. Nicotine patches have been found to possess anti-inflammatory effects in sarcoidosis patients, although whether they had disease-modifying effects requires further investigation. Antimycobacterial treatment (drugs that kill off mycobacteria, the causative agents behind tuberculosis and leprosy) has also proven itself effective in treating chronic cutaneous (that is, it affects the skin) sarcoidosis in one clinical trial. Quercetin has also been tried as a treatment for pulmonary sarcoidosis with some early success in one small trial.

Because of its uncommon nature, the treatment of male reproductive tract sarcoidosis is controversial. Since the differential diagnosis includes testicular cancer, some recommend orchiectomy, even if evidence of sarcoidosis in other organs is present. In the newer approach, testicular, epididymal biopsy and resection of the largest lesion has been proposed.

Symptoms

People with sarcoidosis may have a range of symptoms that do not correspond with objective physical evidence of disease but that still decrease quality of life.

Physical therapy, rehabilitation, and counseling can help avoid deconditioning,:733 and improve social participation, psychological well-being, and activity levels. Key aspects are avoiding exercise intolerance and muscle weakness.:734

Low or moderate-intensity physical training has been shown to improve fatigue, psychological health, and physical functioning in people sarcoidosis without adverse effects. Inspiratory muscle training has also decreased severe fatigue perception in subjects with early stages of sarcoidosis, as well as improving functional and maximal exercise capacity and respiratory muscle strength. The duration, frequency, and physical intensity of exercise needs to accommodate impairments such as joint pain, muscle pain, and fatigue.:734

Neurostimulants such as methylphenidate and modafinil have shown some effectiveness as an adjunct for treatment of sarcoidosis fatigue.:733

Treatments for symptomatic neuropathic pain in sarcoidosis patients is similar to that for other causes, and include antidepressants, anticonvulsants and prolonged-release opioids, however, only 30 to 60% of patients experience limited pain relief.:733

Prognosis

The disease can remit spontaneously or become chronic, with exacerbations and remissions. In some cases, it can progress to pulmonary fibrosis and death. In benign cases, remission can occur in 24 to 36 months without treatment but regular follow ups are required. Some cases, however, may persist several decades. Two-thirds of people with the condition achieve a remission within 10 years of the diagnosis. When the heart is involved, the prognosis is generally less favourable, though corticosteroids appear effective in improving AV conduction. The prognosis tends to be less favourable in African Americans than in white Americans. In a Swedish population-based analysis, the majority of cases who did not have severe disease at diagnosis had comparable mortality to the general population. The risk for premature death was markedly (2.3-fold) increased compared to the general population for a smaller group of cases with severe disease at diagnosis. Serious infections, sometimes multiple during the course of disease, and heart failure might contribute to the higher risk of early death in some patients with sarcoidosis.

Some 1990s studies indicated that people with sarcoidosis appear to be at significantly increased risk for cancer, in particular lung cancer, lymphomas, and cancer in other organs known to be affected in sarcoidosis. In sarcoidosis-lymphoma syndrome, sarcoidosis is followed by the development of a lymphoproliferative disorder such as non-Hodgkin lymphoma. This may be attributed to the underlying immunological abnormalities that occur during the sarcoidosis disease process. Sarcoidosis can also follow cancer or occur concurrently with cancer. There have been reports of hairy cell leukemia, acute myeloid leukemia, and acute myeloblastic leukemia associated with sarcoidosis. Sometimes, sarcoidosis, even untreated, can be complicated by opportunistic infections.

Epidemiology

Sarcoidosis most commonly affects young adults of both sexes, although studies have reported more cases in females. Incidence is highest for individuals younger than 40 and peaks in the age-group from 20 to 29 years; a second peak is observed for women over 50.

Sarcoidosis occurs throughout the world in all races with an average incidence of 16.5 per 100,000 in men and 19 per 100,000 in women. The disease is most common in Northern European countries and the highest annual incidence of 60 per 100,000 is found in Sweden and Iceland. In the United Kingdom the prevalence is 16 in 100,000. In the United States, sarcoidosis is more common in people of African descent than Caucasians, with annual incidence reported as 35.5 and 10.9 per 100,000, respectively. Sarcoidosis is less commonly reported in South America, Spain, India, Canada, and the Philippines. There may be a higher susceptibility to sarcoidosis in those with celiac disease. An association between the two disorders has been suggested.

There also has been a seasonal clustering observed in sarcoidosis-affected individuals. In Greece about 70% of diagnoses occur between March and May every year, in Spain about 50% of diagnoses occur between April and June, and in Japan it is mostly diagnosed during June and July.

The differing incidence across the world may be at least partially attributable to the lack of screening programs in certain regions of the world, and the overshadowing presence of other granulomatous diseases, such as tuberculosis, that may interfere with the diagnosis of sarcoidosis where they are prevalent. There may also be differences in the severity of the disease between people of different ethnicities. Several studies suggest the presentation in people of African origin may be more severe and disseminated than for Caucasians, who are more likely to have asymptomatic disease. Manifestation appears to be slightly different according to race and sex. Erythema nodosum is far more common in men than in women and in Caucasians than in other races. In Japanese people, ophthalmologic and cardiac involvement are more common than in other races.

It is more common in certain occupations, namely firefighters, educators, military personnel, those who work in industries where pesticides are used, law enforcement, and healthcare personnel. In the year after the September 11 attacks, the rate of sarcoidosis incidence went up four-fold (to 86 cases per 100,000).

History

It was first described in 1877 by Dr. Jonathan Hutchinson, a dermatologist as a condition causing red, raised rashes on the face, arms, and hands. In 1889 the term Lupus pernio was coined by Dr. Ernest Besnier, another dermatologist. Later in 1892 lupus pernio's histology was defined. In 1902 bone involvement was first described by a group of three doctors. Between 1909 and 1910 uveitis in sarcoidosis was first described, and later in 1915 it was emphasised, by Dr. Schaumann, that it was a systemic condition. This same year lung involvement was also described. In 1937 uveoparotid fever was first described and likewise in 1941 Löfgren syndrome was first described. In 1958 the first international conference on sarcoidosis was called in London, likewise the first USA sarcoidosis conference occurred in Washington, D.C., in the year 1961. It has also been called Besnier–Boeck disease or Besnier–Boeck–Schaumann disease.

Etymology

The word "sarcoidosis" comes from Greek [σάρκο-] sarcο- meaning "flesh", the suffix -(e)ido (from the Greek εἶδος -eidos [usually omitting the initial e in English as the diphthong epsilon-iota in Classic Greek stands for a long "i" = English ee]) meaning "type", " resembles" or "like", and -sis, a common suffix in Greek meaning "condition". Thus the whole word means "a condition that resembles crude flesh". The first cases of sarcoïdosis, which were recognised as a new pathological entity, in Scandinavia, at the end of the 19th century exhibited skin nodules resembling cutaneous sarcomas, hence the name initially given.

Society and culture

The World Association of Sarcoidosis and Other Granulomatous Disorders (WASOG) is an organisation of physicians involved in the diagnosis and treatment of sarcoidosis and related conditions. WASOG publishes the journal Sarcoidosis, Vasculitis and Diffuse Lung Diseases. Additionally, the Foundation for Sarcoidosis Research (FSR) is devoted to supporting research into sarcoidosis and its possible treatments.

There have been concerns that World Trade Center rescue workers are at a heightened risk for sarcoidosis.

Comedian and actor Bernie Mac had sarcoidosis. In 2005, he mentioned that the disease was in remission. His death on 9 August 2008 was caused by complications from pneumonia, though Mac's agent states the sarcoidosis was not related to his fatal pneumonia.

Karen "Duff" Duffy, MTV personality and actress, was diagnosed with neurosarcoidosis in 1995.

American football player Reggie White died in 2004, with pulmonary and cardiac sarcoidosis being contributing factors to his fatal heart arrhythmia.

Singer Sean Levert died in 2008 of sarcoidosis complications.

Joseph Rago, Pulitzer Prize-winning writer known for his work at The Wall Street Journal, died of sarcoidosis complications in 2017.

Several historical figures are suspected of having suffered from sarcoidosis. In a 2014 letter to the British medical journal The Lancet, it was suggested that the French Revolution leader Maximilien Robespierre may have had sarcoidosis, causing him impairment during his time as head of the Reign of Terror. The symptoms associated with Ludwig van Beethoven's 1827 death have been described as possibly consistent with sarcoidosis. Author Robert Louis Stevenson (1850–1894) had a history of chronic coughs and chest complaints, and sarcoidosis has been suggested as a diagnosis.

Pregnancy

Sarcoidosis generally does not prevent successful pregnancy and delivery; the increase in estrogen levels during pregnancy may even have a slightly beneficial immunomodulatory effect. In most cases, the course of the disease is unaffected by pregnancy, with improvement in a few cases and worsening of symptoms in very few cases, although it is worth noting that a number of the immunosuppressants (such as methotrexate, cyclophosphamide) used in corticosteroid-refractory sarcoidosis are known teratogens. Increased risks associated with sarcoidosis ranging from 30 to 70% have been reported for preeclampsia/eclampsia, cesarian or preterm delivery as well as (non-cardiac) birth defects in first singleton pregnancies. In absolute numbers, birth defects and other complications such as maternal death, cardiac arrest, placental abruption or venous thromboembolism are extremely rare in sarcoidosis pregnancies.