Epileptic Encephalopathy, Early Infantile, 31

A number sign (#) is used with this entry because of evidence that early infantile epileptic encephalopathy-31 (EIEE31) is caused by heterozygous mutation in the DNM1 gene (602377) on chromosome 9q34.

For a general phenotypic description and a discussion of genetic heterogeneity of EIEE, see 308350.

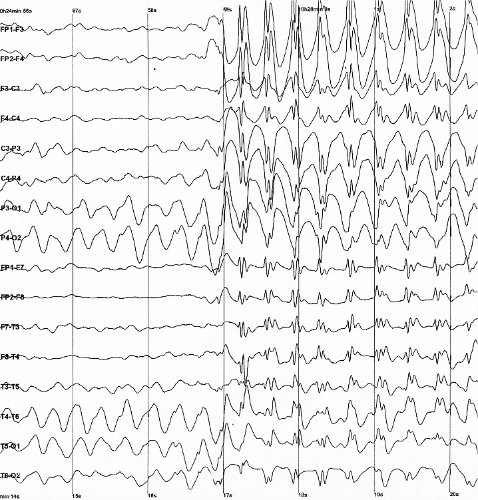

Clinical FeaturesThe EuroEPINOMICS-RES Consortium et al. (2014) reported 5 unrelated patients with early-onset epileptic encephalopathy. All had a normal physical examination at birth. Therapy-resistant seizures, characterized as epileptic spasms, atypical absence, tonic-clonic, atonic, myoclonic, and focal dyscognitive seizures, and obtundation status, began between 2 and 13 months of age. Three children had some delayed development prior to seizure onset, but 2 had normal development and thereafter lost skills. EEG showed variable abnormalities, including hypsarrhythmia, multifocal discharges, spike-wave discharges, and background slowing. At ages 6 to 15 years, the children showed severe or profound intellectual disability with no speech, and hypotonia. Only 1 patient was able to walk, but with an ataxic gait. Two patients had behavioral problems with self-injurious behavior, and 2 had no visual fixation. Brain imaging was normal in 3 patients and showed generalized cerebral atrophy in 2.

The Deciphering Developmental Disorders Study (2015) reported 3 patients with intellectual disability and a variety of syndromic features who carried heterozygous missense mutations in the DNM1 gene. Two of these patients, both males, had seizures; one of these patients additionally had cortical visual impairment and macrocephaly, and the other had gingival overgrowth, abnormal palmar dermatoglyphics, and clinodactyly of the fifth finger. The third patient was a girl who, in addition to global developmental delay, had flat occiput, strabismus, dental crowding, small earlobes, short fingers, and sandal gap.

Molecular GeneticsBy exome sequencing, the EuroEPINOMICS-RES Consortium et al. (2014) identified 5 different de novo heterozygous missense variants in the DNM1 gene (see, e.g., 602377.0001-602377.0003) in 5 of 356 trios in which the proband had early infantile epileptic encephalopathy-31 with unaffected parents. Functional studies of the variants were not performed, but the authors noted that the DNM1 gene plays a role in synaptic transmission and that a mouse model with a heterozygous Dnm1 mutation exhibits epilepsy (Boumil et al., 2010).

The Deciphering Developmental Disorders Study (2015) examined 1,133 children with severe, undiagnosed developmental disorders, and their parents, using a combination of exome sequencing and array-based detection of chromosomal rearrangements. The DNM1 gene was implicated in a gene-specific analysis (p = 1.43 x x 10(-6)). The Deciphering Developmental Disorders Study (2015) identified 3 patients with intellectual disability who had heterozygous de novo missense mutations in the DNM1 gene.

Animal ModelBoumil et al. (2010) found that the 'fitful' (ftfl) mouse mutant results from a heterozygous A408T missense mutation at a conserved region in the middle domain of the Dnm1 protein, affecting only the Dnm1ax isoform. Ftfl mice developed spontaneous limbic and generalized tonic-clonic seizures by 2 or 3 months of age. Homozygous mice had a more severe neurologic phenotype that became apparent at about 3 weeks of age and included ataxia, hearing and visual defects, and lethal seizures. The brains of homozygous ftfl mice showed smaller Purkinje cell dendritic trees in the cerebellum compared to wildtype. In vitro functional expression studies showed that the mutant A408T protein, which was unable to form multimeric Dnm1 complexes, interfered with endocytosis and showed evidence of a dominant-negative effect. Studies of cerebral cortex slices from homozygous mice suggested a defect in vesicle membrane recycling.