Health Effects Of Tobacco

Tobacco use has predominantly negative effects on human health and concern about health effects of tobacco has a long history. Research has focused primarily on cigarette tobacco smoking.

Tobacco smoke contains more than 70 chemicals that cause cancer. Tobacco also contains nicotine, which is a highly addictive psychoactive drug. When tobacco is smoked, nicotine causes physical and psychological dependency. Cigarettes sold in underdeveloped countries tend to have higher tar content, and are less likely to be filtered, potentially increasing vulnerability to tobacco smoking related disease in these regions.

Tobacco use is the single greatest cause of preventable death globally. As many as half of people who use tobacco die from complications of tobacco use. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that each year tobacco causes about 6 million deaths (about 10% of all deaths) with 600,000 of these occurring in non-smokers due to second hand smoke. In the 20th century tobacco is estimated to have caused 100 million deaths. Similarly, the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention describes tobacco use as "the single most important preventable risk to human health in developed countries and an important cause of premature death worldwide." Currently, the number of premature deaths in the U.S. from tobacco use per year outnumber the number of workers employed in the tobacco industry by 4 to 1. According to a 2014 review in the New England Journal of Medicine, tobacco will, if current smoking patterns persist, kill about 1 billion people in the 21st century, half of them before the age of 70.

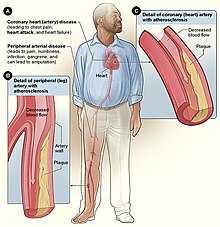

Tobacco use leads most commonly to diseases affecting the heart, liver and lungs. Smoking is a major risk factor for infections like pneumonia, heart attacks, strokes, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) (including emphysema and chronic bronchitis), and several cancers (particularly lung cancer, cancers of the larynx and mouth, bladder cancer, and pancreatic cancer). It also causes peripheral arterial disease and high blood pressure. The effects depend on the number of years that a person smokes and on how much the person smokes. Starting smoking earlier in life and smoking cigarettes higher in tar increases the risk of these diseases. Also, environmental tobacco smoke, or secondhand smoke, has been shown to cause adverse health effects in people of all ages. Tobacco use is a significant factor in miscarriages among pregnant smokers, and it contributes to a number of other health problems of the fetus such as premature birth, low birth weight, and increases by 1.4 to 3 times the chance of sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS). Incidence of erectile dysfunction is approximately 85 percent higher in male smokers compared to non-smokers.

Several countries have taken measures to control the consumption of tobacco with usage and sales restrictions as well as warning messages printed on packaging. Additionally, smoke-free laws that ban smoking in public places such as workplaces, theaters, and bars and restaurants reduce exposure to secondhand smoke and help some people who smoke to quit, without negative economic effects on restaurants or bars. Tobacco taxes that increase the price are also effective, especially in developing countries.

The idea that tobacco use caused some diseases, including mouth cancers, was initially, in the late 1700s and the 1800s, widely accepted by the medical community. In the 1880s, automation slashed the cost of cigarettes, and use expanded. From the 1890s onwards, associations of tobacco use with cancers and vascular disease were regularly reported; a meta-analysis citing 167 other works was published in 1930, and concluded that tobacco use caused cancer. Increasingly solid observational evidence was published throughout the 1930s, and in 1938, Science published a paper showing that tobacco users live substantially shorter lives. Case-control studies were published in Nazi Germany in 1939 and 1943, and one in the Netherlands in 1948, but widespread attention was first drawn by five case-control studies published in 1950 by researchers from the US and UK. These studies were widely criticized as showing correlation, not causality. Follow up prospective cohort studies in the early 1950s clearly found that smokers died faster, and were more likely to die of lung cancer and cardiovascular disease. These results were first widely accepted in the medical community, and publicized among the general public, in the mid-1960s.

History

Pre-cigarette

Concern about health effects of tobacco has a long history. The coughing, throat irritation, and shortness of breath caused by smoking have always been obvious.

During Early Modern times, West African Muslim scholars knew the negative health effects of smoking tobacco. The dangers of tobacco smoking were documented in the Timbuktu manuscripts.

Pipe smoking gradually became generally accepted as a cause of mouth cancers following work done in the 1700s. An association between a variety of cancers and tobacco use was repeatedly observed from the late 1800s into the early 1920s. An association between tobacco use and vascular disease was reported from the late 1800s onwards.

Gideon Lincecum, an American naturalist and practitioner of botanical medicine, wrote in the early 19th century on tobacco: "This poisonous plant has been used a great deal as a medicine by the old school faculty, and thousands have been slain by it. ... It is a very dangerous article, and use it as you will, it always diminishes the vital energies in exact proportion to the quantity used – it may be slowly, but it is very sure."

The 1880s invention of automated cigarette-making machinery in the American South made it possible to mass-produce cigarettes at low cost, and smoking became common. This led to a backlash and a tobacco prohibition movement, which challenged tobacco use as harmful and brought about some bans on tobacco sale and use. In 1912, American Dr. Isaac Adler was the first to strongly suggest that lung cancer is related to smoking. In 1924, economist Irving Fisher wrote an anti-smoking article for Reader's Digest which said "...tobacco lowers the whole tone of the body and decreases its vital power and resistance ... tobacco acts like a narcotic poison, like opium, and like alcohol, though usually in a less degree". Reader's Digest for many years published frequent anti-smoking articles.

Prior to World War I, lung cancer was considered to be a rare disease, which most physicians would never see during their career. With the postwar rise in popularity of cigarette smoking, however, came an epidemic of lung cancer.

Early observational studies

From the 1890s onwards, associations of tobacco use with cancers and vascular disease were regularly reported. In 1930, Fritz Lickint of Dresden, Germany, published a metaanalysis citing 167 other works to link tobacco use to lung cancer. Lickint showed that lung cancer sufferers were likely to be smokers. He also argued that tobacco use was the best way to explain the fact that lung cancer struck men four or five times more often than women (since women smoked much less), and discussed the causal effect of smoking on cancers of the liver and bladder.

Rolleston, J. D. (1932-07-01). "The Cigarette Habit". British Journal of Inebriety (Alcoholism and Drug Addiction). 30 (1): 1–27. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.1932.tb04849.x. ISSN 1360-0443.

More observational evidence was published throughout the 1930s, and in 1938, Science published a paper showing that tobacco users live substantially shorter lives. It built a survival curve from family history records kept at the Johns Hopkins School of Hygiene and Public Health. This result was ignored or incorrectly explained away.

An association between tobacco and heart attacks was first mentioned in the 1930; a large case–control study found a significant association in 1940, but avoided saying anything about cause, on the grounds that such a conclusion would cause controversy and doctors were not yet ready for it.

Official hostility to tobacco use was widespread in Nazi Germany where case-control studies were published in 1939 and 1943. Another was published in the Netherlands in 1948. A case-control study on lung cancer and smoking, done in 1939 by Franz Hermann Müller, had serious weaknesses in its methodology, but study design problems were better addressed in subsequent studies. The association of anti-tobacco research and public health measures with the Nazi leadership may have contributed to the lack of attention paid to these studies. They were also published in German and Dutch. These studies were widely ignored. In 1947 the British Medical Council held a conference to discuss the reason for the rise in lung cancer deaths; unaware of the German studies, they planned and started their own.

Five case-control studies published in 1950 by researchers from the US and UK did draw widespread attention. The strongest results were found by "Smoking and carcinoma of the lung. Preliminary report", by Richard Doll and Austin Hill, and the 1950 Wynder and Graham Study, entitled "Tobacco Smoking as a Possible Etiologic Factor in Bronchiogenic Carcinoma: A Study of Six Hundred and Eighty-Four Proved Cases". These two studies were the largest, and the only ones to carefully exclude ex-smokers from their nonsmokers group. The other three studies also reported that, to quote one, "smoking was powerfully implicated in the causation of lung cancer". The Doll and Hill paper reported that "heavy smokers were fifty times as likely as non-smokers to contract lung cancer".

Causality

The case-control studies clearly showed a close link between smoking and lung cancer, but were criticized for not showing causality. Follow-up large prospective cohort studies in the early 1950s showed clearly that smokers died faster, and were more likely to die of lung cancer, cardiovascular disease, and a list of other diseases which lengthened as the studies continued

The British Doctors Study, a longitudinal study of some 40,000 doctors, began in 1951. By 1954 it had evidence from three years of doctors' deaths, based on which the government issued advice that smoking and lung cancer rates were related (the British Doctors Study last reported in 2001, by which time there were approximately 40 linked diseases). The British Doctors Study demonstrated that about half of the persistent cigarette smokers born in 1900–1909 were eventually killed by their addiction (calculated from the logarithms of the probabilities of surviving from 35–70, 70–80, and 80–90) and about two thirds of the persistent cigarette smokers born in the 1920s would eventually be killed by their addiction.

Public awareness

In 1953, scientists at the Sloan-Kettering Institute in New York City demonstrated that cigarette tar painted on the skin of mice caused fatal cancers. This work attracted much media attention; the New York Times and Life both covered the issue. The Reader's Digest published an article entitled "Cancer by the Carton".:14

On January 11, 1964, the United States Surgeon General's Report on Smoking and Health was published; this led millions of American smokers to quit, the banning of certain advertising, and the requirement of warning labels on tobacco products.

These results were first widely accepted in the medical community, and publicized among the general public, in the mid-1960s. The medical community's resistance to the idea that tobacco caused disease has been attributed to bias from nicotine-dependent doctors, the novelty of the adaptations needed to apply epidemiological techniques and heuristics to non-infectious diseases, and tobacco industry pressure.

The health effects of smoking have been significant for the development of the science of epidemiology. As the mechanism of carcinogenicity is radiomimetic or radiological, the effects are stochastic. Definite statements can be made only on the relative increased or decreased probabilities of contracting a given disease. For a particular individual, it is impossible to definitively prove a direct causal link between exposure to a radiomimetic poison such as tobacco smoke and the cancer that follows; such statements can only be made at the aggregate population level. Tobacco companies have capitalized on this philosophical objection and exploited the doubts of clinicians, who consider only individual cases, on the causal link in the stochastic expression of the toxicity as actual disease.

There have been multiple court cases against tobacco companies for having researched the health effects of tobacco, but having then suppressed the findings or formatted them to imply lessened or no hazard.

After a ban on smoking in all enclosed public places was introduced in Scotland in March 2006, there was a 17 percent reduction in hospital admissions for acute coronary syndrome. 67% of the decrease occurred in non-smokers.

Health effects of smoking

Smoking most commonly leads to diseases affecting the heart and lungs and will commonly affect areas such as hands or feet. First signs of smoking related health issues often show up as numbness in the extremities, with smoking being a major risk factor for heart attacks, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), emphysema, and cancer, particularly lung cancer, cancers of the larynx and mouth, and pancreatic cancer. Overall life expectancy is also reduced in long term smokers, with estimates ranging from 10 to 17.9 years fewer than nonsmokers. About one half of long term male smokers will die of illness due to smoking. The association of smoking with lung cancer is strongest, both in the public perception and etiologically. Among male smokers, the lifetime risk of developing lung cancer is 17.2%; among female smokers, the risk is 11.6%. This risk is significantly lower in nonsmokers: 1.3% in men and 1.4% in women.

A person's increased risk of contracting disease is related to the length of time that a person continues to smoke as well as the amount smoked. However, even smoking one cigarette a day raises the risk of coronary heart disease by about 50% or more, and for stroke by about 30%. Smoking 20 cigarettes a day entails a higher risk, but not proportionately.

If someone stops smoking, then these chances gradually decrease as the damage to their body is repaired. A year after quitting, the risk of contracting heart disease is half that of a continuing smoker. The health risks of smoking are not uniform across all smokers. Risks vary according to the amount of tobacco smoked, with those who smoke more at greater risk. Smoking so-called "light" cigarettes does not reduce the risk.

Mortality

Smoking is the cause of about 5 million deaths per year. This makes it the most common cause of preventable early death. One study found that male and female smokers lose on average of 13.2 and 14.5 years of life, respectively. Another found a loss of life of 6.8 years. Each cigarette that is smoked is estimated to shorten life by an average of 11 minutes. At least half of all lifelong smokers die earlier as a result of smoking. Smokers are three times as likely to die before the age of 60 or 70 as non-smokers.

In the United States, cigarette smoking and exposure to tobacco smoke accounts for roughly one in five, or at least 443,000 premature deaths annually. To put this into context, ABC's Peter Jennings (who would later die at 67 from complications of lung cancer due to his life-long smoking habit) famously reported that in the US alone, tobacco kills the equivalent of three jumbo jets full of people crashing every day, with no survivors. On a worldwide basis, this equates to a single jumbo jet every hour.

A 2015 study found that about 17% of mortality due to cigarette smoking in the United States is due to diseases other than those usually believed to be related.

It is estimated that there are between 1 and 1.4 deaths per million cigarettes smoked. In fact, cigarette factories are the most deadly factories in the history of the world. See the below chart detailing the highest-producing cigarette factories, and their estimated deaths caused annually due to the health detriments of cigarettes.

Share of deaths from smoking, 2017

The number of deaths attributed to smoking per 100,000 people in 2017

Cancer

Play media

Play mediaThe primary risks of tobacco usage include many forms of cancer, particularly lung cancer, kidney cancer, cancer of the larynx and head and neck, bladder cancer, cancer of the esophagus, cancer of the pancreas and stomach cancer. Studies have established a relationship between tobacco smoke, including secondhand smoke, and cervical cancer in women. There is some evidence suggesting a small increased risk of myeloid leukemia, squamous cell sinonasal cancer, liver cancer, colorectal cancer, cancers of the gallbladder, the adrenal gland, the small intestine, and various childhood cancers. The possible connection between breast cancer and tobacco is still uncertain.

Lung cancer risk is highly affected by smoking, with up to 90% of cases being caused by tobacco smoking. Risk of developing lung cancer increases with number of years smoking and number of cigarettes smoked per day. Smoking can be linked to all subtypes of lung cancer. Small-cell carcinoma (SCLC) is the most closely associated with almost 100% of cases occurring in smokers. This form of cancer has been identified with autocrine growth loops, proto-oncogene activation and inhibition of tumour suppressor genes. SCLC may originate from neuroendocrine cells located in the bronchus called Feyrter cells.

The risk of dying from lung cancer before age 85 is 22.1% for a male smoker and 11.9% for a female smoker, in the absence of competing causes of death. The corresponding estimates for lifelong nonsmokers are a 1.1% probability of dying from lung cancer before age 85 for a man of European descent, and a 0.8% probability for a woman.

Pulmonary

In smoking, long term exposure to compounds found in the smoke (e.g., carbon monoxide and cyanide) are believed to be responsible for pulmonary damage and for loss of elasticity in the alveoli, leading to emphysema and COPD. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) caused by smoking is a permanent, incurable (often terminal) reduction of pulmonary capacity characterised by shortness of breath, wheezing, persistent cough with sputum, and damage to the lungs, including emphysema and chronic bronchitis. The carcinogen acrolein and its derivatives also contribute to the chronic inflammation present in COPD.

Cardiovascular disease

Inhalation of tobacco smoke causes several immediate responses within the heart and blood vessels. Within one minute the heart rate begins to rise, increasing by as much as 30 percent during the first 10 minutes of smoking. Carbon monoxide in tobacco smoke exerts negative effects by reducing the blood's ability to carry oxygen.

Smoking also increases the chance of heart disease, stroke, atherosclerosis, and peripheral vascular disease. Several ingredients of tobacco lead to the narrowing of blood vessels, increasing the likelihood of a blockage, and thus a heart attack or stroke. According to a study by an international team of researchers, people under 40 are five times more likely to have a heart attack if they smoke.

Exposure to tobacco smoke is known to increase oxidative stress in the body by various mechanisms, including depletion of plasma antioxidants such as vitamin C.

Recent research by American biologists has shown that cigarette smoke also influences the process of cell division in the cardiac muscle and changes the heart's shape.

The usage of tobacco has also been linked to Buerger's disease (thromboangiitis obliterans), the acute inflammation and thrombosis (clotting) of arteries and veins of the hands and feet.

Although cigarette smoking causes a greater increase in the risk of cancer than cigar smoking, cigar smokers still have an increased risk for many health problems, including cancer, when compared to non-smokers. As for second-hand smoke, the NIH study points to the large amount of smoke generated by one cigar, saying "cigars can contribute substantial amounts of tobacco smoke to the indoor environment; and, when large numbers of cigar smokers congregate in a cigar smoking event, the amount of ETS (i.e. second-hand smoke) produced is sufficient to be a health concern for those regularly required to work in those environments."

Smoking tends to increase blood cholesterol levels. Furthermore, the ratio of high-density lipoprotein (HDL, also known as the "good" cholesterol) to low-density lipoprotein (LDL, also known as the "bad" cholesterol) tends to be lower in smokers compared to non-smokers. Smoking also raises the levels of fibrinogen and increases platelet production (both involved in blood clotting) which makes the blood thicker and more likely to clot. Carbon monoxide binds to hemoglobin (the oxygen-carrying component in red blood cells), resulting in a much stabler complex than hemoglobin bound with oxygen or carbon dioxide—the result is permanent loss of blood cell functionality. Blood cells are naturally recycled after a certain period of time, allowing for the creation of new, functional red blood cells. However, if carbon monoxide exposure reaches a certain point before they can be recycled, hypoxia (and later death) occurs. All these factors make smokers more at risk of developing various forms of arteriosclerosis (hardening of the arteries). As the arteriosclerosis progresses, blood flows less easily through rigid and narrowed blood vessels, making the blood more likely to form a thrombosis (clot). Sudden blockage of a blood vessel may lead to an infarction (stroke or heart attack). However, it is also worth noting that the effects of smoking on the heart may be more subtle. These conditions may develop gradually given the smoking-healing cycle (the human body heals itself between periods of smoking), and therefore a smoker may develop less significant disorders such as worsening or maintenance of unpleasant dermatological conditions, e.g. eczema, due to reduced blood supply. Smoking also increases blood pressure and weakens blood vessels.

Renal

In addition to increasing the risk of kidney cancer, smoking can also contribute to additional renal damage. Smokers are at a significantly increased risk for chronic kidney disease than non-smokers. A history of smoking encourages the progression of diabetic nephropathy.

Influenza

A study of an outbreak of an (H1N1) influenza in an Israeli military unit of 336 healthy young men to determine the relation of cigarette smoking to the incidence of clinically apparent influenza, revealed that, of 168 smokers, 68.5 percent had influenza, as compared with 47.2 percent of nonsmokers. Influenza was also more severe in the smokers; 50.6 percent of them lost work days or required bed rest, or both, as compared with 30.1 percent of the nonsmokers.

According to a study of 1,900 male cadets after the 1968 Hong Kong A2 influenza epidemic at a South Carolina military academy, compared with nonsmokers, heavy smokers (more than 20 cigarettes per day) had 21% more illnesses and 20% more bed rest, light smokers (20 cigarettes or fewer per day) had 10% more illnesses and 7% more bed rest.

The effect of cigarette smoking upon epidemic influenza was studied prospectively among 1,811 male college students. Clinical influenza incidence among those who daily smoked 21 or more cigarettes was 21% higher than that of non-smokers. Influenza incidence among smokers of 1 to 20 cigarettes daily was intermediate between non-smokers and heavy cigarette smokers.

Surveillance of a 1979 influenza outbreak at a military base for women in Israel revealed that influenza symptoms developed in 60.0% of the current smokers vs. 41.6% of the nonsmokers.

Smoking seems to cause a higher relative influenza-risk in older populations than in younger populations. In a prospective study of community-dwelling people 60–90 years of age, during 1993, of unimmunized people 23% of smokers had clinical influenza as compared with 6% of non-smokers.

Smoking may substantially contribute to the growth of influenza epidemics affecting the entire population. However, the proportion of influenza cases in the general non-smoking population attributable to smokers has not yet been calculated.

Mouth

Perhaps the most serious oral condition that can arise is that of oral cancer. However, smoking also increases the risk for various other oral diseases, some almost completely exclusive to tobacco users. The National Institutes of Health, through the National Cancer Institute, determined in 1998 that "cigar smoking causes a variety of cancers including cancers of the oral cavity (lip, tongue, mouth, throat), esophagus, larynx, and lung." Pipe smoking involves significant health risks, particularly oral cancer. Roughly half of periodontitis or inflammation around the teeth cases are attributed to current or former smoking. Smokeless tobacco causes gingival recession and white mucosal lesions. Up to 90% of periodontitis patients who are not helped by common modes of treatment are smokers. Smokers have significantly greater loss of bone height than nonsmokers, and the trend can be extended to pipe smokers to have more bone loss than nonsmokers.

Smoking has been proven to be an important factor in the staining of teeth. Halitosis or bad breath is common among tobacco smokers. Tooth loss has been shown to be 2 to 3 times higher in smokers than in non-smokers. In addition, complications may further include leukoplakia, the adherent white plaques or patches on the mucous membranes of the oral cavity, including the tongue.

Infection

Smoking is also linked to susceptibility to infectious diseases, particularly in the lungs (pneumonia). Smoking more than 20 cigarettes a day increases the risk of tuberculosis by two to four times, and being a current smoker has been linked to a fourfold increase in the risk of invasive disease caused by the pathogenic bacteria Streptococcus pneumoniae. It is believed that smoking increases the risk of these and other pulmonary and respiratory tract infections both through structural damage and through effects on the immune system. The effects on the immune system include an increase in CD4+ cell production attributable to nicotine, which has tentatively been linked to increased HIV susceptibility.

Smoking increases the risk of Kaposi's sarcoma in people without HIV infection. One study found this only with the male population and could not draw any conclusions for the female participants in the study.

Impotence

The incidence of impotence (difficulty achieving and maintaining penile erection) is approximately 85 percent higher in male smokers compared to non-smokers. Smoking is a key cause of erectile dysfunction (ED). It causes impotence because it promotes arterial narrowing and damages cells lining the inside of the arteries, thus leading to reduce penile blood flow.

Female infertility

Smoking is harmful to the ovaries, potentially causing female infertility, and the degree of damage is dependent upon the amount and length of time a woman smokes. Nicotine and other harmful chemicals in cigarettes interfere with the body's ability to create estrogen, a hormone that regulates folliculogenesis and ovulation. Also, cigarette smoking interferes with folliculogenesis, embryo transport, endometrial receptivity, endometrial angiogenesis, uterine blood flow and the uterine myometrium. Some damage is irreversible, but stopping smoking can prevent further damage. Smokers are 60% more likely to be infertile than non-smokers. Smoking reduces the chances of in vitro fertilization (IVF) producing a live birth by 34% and increases the risk of an IVF pregnancy miscarrying by 30%.

Psychological

American Psychologist stated, "Smokers often report that cigarettes help relieve feelings of stress. However, the stress levels of adult smokers are slightly higher than those of nonsmokers, adolescent smokers report increasing levels of stress as they develop regular patterns of smoking, and smoking cessation leads to reduced stress. Far from acting as an aid for mood control, nicotine dependency seems to exacerbate stress. This is confirmed in the daily mood patterns described by smokers, with normal moods during smoking and worsening moods between cigarettes. Thus, the apparent relaxant effect of smoking only reflects the reversal of the tension and irritability that develop during nicotine depletion. Dependent smokers need nicotine to remain feeling normal."

Immediate effects

Users report feelings of relaxation, sharpness, calmness, and alertness. Those new to smoking may experience nausea, dizziness, increased blood pressure, narrowed arteries, and rapid heart beat. Generally, the unpleasant symptoms will eventually vanish over time, with repeated use, as the body builds a tolerance to the chemicals in the cigarettes, such as nicotine.

Stress

Smokers report higher levels of everyday stress. Several studies have monitored feelings of stress over time and found reduced stress after quitting.

The deleterious mood effects of abstinence explain why smokers suffer more daily stress than non-smokers and become less stressed when they quit smoking. Deprivation reversal also explains much of the arousal data, with deprived smokers being less vigilant and less