Dementia With Lewy Bodies

Dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB) is a type of dementia accompanied by changes in sleep, behavior, cognition, movement, and autonomic bodily functions. Memory loss is not always an early symptom. The disease worsens over time and is usually diagnosed when cognitive decline interferes with normal daily functioning. Together with Parkinson's disease dementia, DLB is one of the two Lewy body dementias. It is a common form of dementia, but the prevalence is not known accurately and many diagnoses are missed. The disease was first described by Kenji Kosaka in 1976.

REM sleep behavior disorder (RBD)—in which people lose the muscle paralysis that normally occurs during REM sleep and act out their dreams—is a core feature. RBD may appear years or decades before other symptoms. Other core features are visual hallucinations, marked fluctuations in attention or alertness, and parkinsonism (slowness of movement, trouble walking, or rigidity). Not all features must be present for a diagnosis. Definitive diagnosis usually requires an autopsy, but a likely diagnosis is made based on symptoms and tests which may include blood tests, neuropsychological tests, imaging, and sleep studies.

Most people with DLB do not have affected family members, although occasionally DLB runs in a family. The exact cause is unknown, but involves widespread deposits of abnormal clumps of protein that form in neurons of the diseased brain. Known as Lewy bodies (discovered in 1912 by Frederic Lewy) and Lewy neurites, these clumps affect both the central nervous system and the autonomic nervous system. Heart function and every level of gastrointestinal function—from chewing to defecation—can be affected, constipation being one of the most common symptoms. Low blood pressure upon standing can also be a symptom. DLB also affects behavior; mood changes such as depression and apathy are common.

DLB typically begins after the age of fifty and people with the disease have a life expectancy of about eight years after diagnosis. There is no cure or medication to stop the disease from progressing, and people in the latter stages of DLB may be unable to care for themselves. Treatments aim to relieve some of the symptoms and reduce the burden on caregivers. Medicines such as donepezil and rivastigmine are effective at improving cognition and overall functioning, and melatonin can be used for sleep-related symptoms.[9] Antipsychotics are usually avoided, even for hallucinations, because severe and life-threatening reactions occur in almost half of people with DLB,[10] and their use can result in death.[11] Management of the many different symptoms is challenging, as it involves multiple specialties and education of caregivers.

Classification

Dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB) is a type of dementia that is progressive and neurodegenerative; that is, it is characterized by degeneration of the central nervous system that worsens over time.

Dementia with Lewy bodies is sometimes classified in other ways. It is one of the two Lewy body dementias, along with Parkinson's disease dementia. The atypical parkinsonian syndromes include DLB, along with other conditions. Lastly, DLB is a synucleinopathy, meaning that it is characterized by abnormal deposits of alpha-synuclein protein in the brain. The synucleinopathies include Parkinson's disease, multiple system atrophy, and other rarer conditions.

Signs and symptoms

DLB is dementia that occurs with "some combination of fluctuating cognition, recurrent visual hallucinations, rapid eye movement (REM) sleep behavior disorder (RBD), and parkinsonism starting with or after the dementia diagnosis", according to Armstrong (2019). DLB has widely varying symptoms and is more complex than many other dementias. Several areas of functioning can be affected by Lewy pathology, in which the alpha-synuclein deposits that cause DLB damage many different regions of the nervous system (such as the autonomic nervous system and numerous regions of the brain).

In DLB, there is an identifiable set of early signs and symptoms; these are called the prodromal, or pre-dementia, phase of the disease. These early signs can appear 15 years or more before dementia develops. The earliest signs are constipation and dizziness from autonomic dysfunction, hyposmia (reduced ability to smell), visual hallucinations, and RBD. RBD may appear years or decades before other symptoms.[22] Memory loss is not always an early symptom.

The symptoms can be divided into essential, core, and supportive features. Dementia is the essential feature and must be present for diagnosis, while core and supportive features are further evidence in support of diagnosis (see diagnostic criteria below).[24]

Essential feature

A dementia diagnosis is made after cognitive decline progresses to a point of interfering with normal daily activities, or social or occupational function.[24] While dementia is an essential feature of DLB, it does not always appear early on, and is more likely to present as the condition progresses.[24]

Core features

While specific symptoms may vary, the core features of DLB are fluctuating cognition, alertness or attention; REM sleep behavior disorder; one or more of the cardinal features of parkinsonism, not due to medication or stroke; and repeated visual hallucinations.

The 2017 Fourth Consensus Report of the DLB Consortium determined these to be core features based on the availability of high-quality evidence indicating they are highly specific to the condition.[24]

Fluctuating cognition, alertness or attention

Besides memory loss, the three most common cognitive symptoms in DLB are impairments of attention, executive function, and visuospatial function. These impairments are present early in the course of the disease.[24] Individuals with DLB may be easily distracted, have a hard time focusing on tasks, or appear to be "delirium-like", "zoning out", or in states of altered consciousness[24] with spells of confusion, agitation or incoherent speech. They may have disorganized speech and their ability to organize their thoughts may change during the day.[24] Executive function describes attentional and behavioral controls, memory and cognitive flexibility that aid problem solving and planning. Problems with executive function surface in activities requiring planning and organizing. Deficits can manifest in impaired job performance, inability to follow conversations, difficulties with multitasking, or mistakes in driving, such as misjudging distances or becoming lost. The person with DLB may experience disorders of wakefulness or sleep disorders (in addition to REM sleep behavior disorder) that can be severe.[22] These disorders include daytime sleepiness, drowsiness or napping more than two hours a day, insomnia, periodic limb movements, restless legs syndrome and sleep apnea.[22]

REM sleep behavior disorder

and dementia with Lewy bodies

—B. Tousi (2017), Diagnosis and Management of Cognitive and Behavioral Changes in Dementia With Lewy Bodies.[32]

REM sleep behavior disorder (RBD) is a parasomnia in which individuals lose the paralysis of muscles (atonia) that is normal during rapid eye movement (REM) sleep, and consequently act out their dreams or make other abnormal movements or vocalizations. About 80% of those with DLB have RBD. Abnormal sleep behaviors may begin before cognitive decline is observed,[24] and may appear decades before any other symptoms, often as the first clinical indication of DLB and an early sign of a synucleinopathy. On autopsy, 94 to 98% of individuals with polysomnography-confirmed RBD have a synucleinopathy—most commonly DLB or Parkinson's disease[36] in about equal proportions. More than three out of four people with RBD are diagnosed with a neurodegenerative condition within ten years, but additional neurodegenerative diagnoses may emerge up to 50 years after RBD diagnosis. RBD may subside over time.[24]

Individuals with RBD may not be aware that they act out their dreams. RBD behaviors may include yelling, screaming, laughing, crying, unintelligible talking, nonviolent flailing, or more violent punching, kicking, choking, or scratching. The reported dream enactment behaviors are frequently violent, and involve a theme of being chased or attacked.[36] People with RBD may fall out of bed or injure themselves or their bed partners,[24][36] which may cause bruises, fractures, or subdural hematomae. Because people are more likely to remember or report violent dreams and behaviors—and to be referred to a specialist when injury occurs—recall or selection bias may explain the prevalence of violence reported in RBD.

Parkinsonism

Parkinsonism is a clinical syndrome characterized by slowness of movement, rigidity, postural instability, and tremor; it is found in DLB and many other conditions like Parkinson's disease, Parkinson's disease dementia, and others. Parkinsonism occurs in more than 85% of people with DLB, who may have one or more of these cardinal features,[24] although tremor at rest is less common.[48]

Motor symptoms may include shuffling gait, problems with balance, falls, blank expression, reduced range of facial expression, and low speech volume or a weak voice. Presentation of motor symptoms is variable, but they are usually symmetric, presenting on both sides of the body. Only one of the cardinal symptoms of parkinsonism may be present, and the symptoms may be less severe than in persons with Parkinson's disease.[50]

Visual hallucinations

Up to 80% of people with DLB have visual hallucinations, typically early in the course of the disease.[24] They are recurrent and frequent; may be scenic, elaborate and detailed; and usually involve animated perceptions of animals or people, including children and family members. Examples of visual hallucinations "vary from 'little people' who casually walk around the house, 'ghosts' of dead parents who sit quietly at the bedside, to 'bicycles' that hang off of trees in the back yard".

These hallucinations can sometimes provoke fear, although their content is more typically neutral. In some cases, the person with DLB may have insight that the hallucinations are not real. Among those with more disrupted cognition, the hallucinations can become more complex, and they may be less aware that their hallucinations are not real.[55] Visual misperceptions or illusions are also common in DLB but differ from visual hallucinations. While visual hallucinations occur in the absence of real stimuli, visual illusions occur when real stimuli are incorrectly perceived;[55] for example, a person with DLB may misinterpret a floor lamp for a person.

Supportive features

Supportive features of DLB have less diagnostic weight, but they provide evidence for the diagnosis.[24] Supportive features may be present early in the progression, and persist over time; they are common but they are not specific to the diagnosis. The supportive features are:

- marked sensitivity to antipsychotics (neuroleptics);

- marked dysautonomia (autonomic dysfunction) in which the autonomic nervous system does not work properly;

- hallucinations in senses other than vision (hearing, touch, taste, and smell;[56]

- hypersomnia (excessive sleepiness);

- hyposmia (reduced ability to smell);

- false beliefs and delusions organized around a common theme;

- postural instability, loss of consciousness, and frequent falls;

- apathy, anxiety, or depression.

Partly because of loss of cells that release the neurotransmitter dopamine, people with DLB may have neuroleptic malignant syndrome, impairments in cognition or alertness, or irreversible exacerbation of parkinsonism including severe rigidity, and dysautonomia from the use of antipsychotics.[58]

Dysautonomia (autonomic dysfunction) occurs when Lewy pathology affects the peripheral autonomic nervous system (the nerves that serve organs such as the intestines, heart, and urinary tract). The first signs of autonomic dysfunction are often subtle. Symptoms include blood pressure problems such as orthostatic hypotension (dizziness after standing up) and supine hypertension; constipation, urinary problems, and sexual dysfunction; loss of or reduced ability to smell; and excessive sweating, drooling, or salivation, and problems swallowing (dysphagia).

Alpha-synuclein deposits can affect cardiac muscle and blood vessels. "Degeneration of the cardiac sympathetic nerves is a neuropathological feature" of the Lewy body dementias, according to Yamada et al. Almost all people with synucleinopathies have cardiovascular dysfunction, although most are asymptomatic. Between 50 and 60% of individuals with DLB have orthostatic hypotension due to reduced blood flow, which can result in lightheadedness, feeling faint, and blurred vision.

From chewing to defecation, alpha-synuclein deposits affect every level of gastrointestinal function.[68] Almost all persons with DLB have upper gastrointestinal tract dysfunction (such as gastroparesis, delayed gastric emptying) or lower gastrointestinal dysfunction (such as constipation and prolonged stool transit time). Persons with Lewy body dementia almost universally experience nausea, gastric retention, or abdominal distention from delayed gastric emptying. Problems with gastrointestinal function can affect medication absorption.[68] Constipation can present a decade before diagnosis, and is one of the most common symptoms for people with Lewy body dementia.[68] Dysphagia is milder than in other synucleinopathies and presents later. Urinary difficulties (urinary retention, waking at night to urinate, increased urinary frequency and urgency, and over- or underactive bladder) typically appear later and may be mild or moderate. Sexual dysfunction usually appears early in synucleinopathies, and may include erectile dysfunction and difficulty achieving orgasm or ejaculating.

Among the other supportive features, psychiatric symptoms are often present when the individual first comes to clinical attention and are more likely, compared to AD, to cause more impairment. About one-third of people with DLB have depression, and they often have anxiety as well.[10] Anxiety leads to increased risk of falls,[74] and apathy may lead to less social interaction.

Agitation, behavioral disturbances,[75] and delusions typically appear later in the course of the disease. Delusions may have a paranoid quality, involving themes like a house being broken in to, infidelity, or abandonment.[56] Individuals with DLB who misplace items may have delusions about theft. Capgras delusion may occur, in which the person with DLB loses knowledge of the spouse, caregiver, or partner's face, and is convinced that an imposter has replaced them. Hallucinations in other modalities are sometimes present, but are less frequent.[56]

Sleep disorders (disrupted sleep cycles, sleep apnea, and arousal from periodic limb movement disorder) are common in DLB and may lead to hypersomnia. Loss of sense of smell may occur several years before other symptoms.

Causes

Like other synucleinopathies, the exact cause of DLB is unknown. Synucleinopathies are typically caused by interactions of genetic and environmental influences. Most people with DLB do not have affected family members, although occasionally DLB runs in a family. The heritability of DLB is thought to be around 30% (that is, about 70% of traits associated with DLB are not inherited).[81]

There is overlap in the genetic risk factors for DLB, Alzheimer's disease (AD), Parkinson's disease, and Parkinson's disease dementia. The APOE gene has three common variants. One, APOE ε4, is a risk factor for DLB and Alzheimer's disease, whereas APOE ε2 may be protective against both. Mutations in GBA, a gene for a lysosomal enzyme, are associated with both DLB and Parkinson's disease. Rarely, mutations in SNCA, the gene for alpha-synuclein, or LRRK2, a gene for a kinase enzyme, can cause any of DLB, Alzheimer's disease, Parkinson's disease or Parkinson's disease dementia. This suggests some shared genetic pathology may underlie all four diseases.

The greatest risk of developing DLB is being over the age of 50. Having REM sleep behavior disorder or Parkinson's disease confers a higher risk for developing DLB. Risk of developing DLB has not been linked to any specific lifestyle factors. Risk factors for rapid conversion of RBD to a synucleinopathy include impairments in color vision or the ability to smell, mild cognitive impairment, and abnormal dopaminergic imaging.

Pathophysiology

DLB is characterized by the development of abnormal collections of alpha-synuclein protein within diseased brain neurons, known as Lewy bodies and Lewy neurites. When these clumps of protein form, neurons function less optimally and eventually die. Neuronal loss in DLB leads to profound dopamine dysfunction and marked cholinergic pathology; other neurotransmitters might be affected, but less is known about them. Damage in the brain is widespread, and affects many domains of functioning. Loss of acetylcholine-producing neurons is thought to account for degeneration in memory and learning, while the death of dopamine-producing neurons appears to be responsible for degeneration of behavior, cognition, mood, movement, motivation, and sleep. The extent of Lewy body neuronal damage is a key determinant of dementia in the Lewy body disorders.

The precise mechanisms contributing to DLB are not well understood and are a matter of some controversy.[92] The role of alpha-synuclein deposits is unclear, because individuals with no signs of DLB have been found on autopsy to have advanced alpha-synuclein pathology. The relationship between Lewy pathology and widespread cell death is contentious.[92] It is not known if the pathology spreads between cells or follows another pattern. The mechanisms that contribute to cell death, how the disease advances through the brain, and the timing of cognitive decline are all poorly understood.[92] There is no model to account for the specific neurons and brain regions that are affected.[92]

Autopsy studies and amyloid imaging studies using Pittsburgh compound B (PiB) indicate that tau protein pathology and amyloid plaques, which are hallmarks of AD, are also common in DLB and more common than in Parkinson's disease dementia. Amyloid-beta (Aβ) deposits are found in the tauopathies—neurodegenerative diseases characterized by neurofibrillary tangles of hyperphosphorylated tau protein—but the mechanism underlying dementia is often mixed, and Aβ is also a factor in DLB.

A proposed pathophysiology for RBD implicates neurons in the reticular formation that regulate REM sleep. RBD might appear decades earlier than other symptoms in the Lewy body dementias because these cells are affected earlier, before spreading to other brain regions.

Diagnosis

Dementia with Lewy bodies can only be definitively diagnosed after death with an autopsy of the brain (or in rare familial cases, via a genetic test), so diagnosis of the living is referred to as probable or possible.[24] Diagnosing DLB can be challenging because of the wide range of symptoms with differing levels of severity in each individual. DLB is often misdiagnosed or, in its early stages, confused with Alzheimer’s disease. As many as one in three diagnoses of DLB may be missed. Another complicating factor is that DLB can occur along with AD; autopsy reveals that most people with DLB have some level of changes attributed to AD in their brains, which contributes to the wide-ranging variety of symptoms and diagnostic difficulty.[106] Despite the difficulty in diagnosis, a prompt diagnosis is important because of the serious risks of sensitivity to antipsychotics and the need to inform both the person with DLB and the person's caregivers about those medications' side effects. The management of DLB is difficult in comparison to many other neurodegenerative diseases, so an accurate diagnosis is important.

Criteria

The 2017 Fourth Consensus Report established diagnostic criteria for probable and possible DLB, recognizing advances in detection since the earlier Third Consensus (2005) version. The 2017 criteria are based on essential, core, and supportive clinical features, and diagnostic biomarkers.

The essential feature is dementia; for a DLB diagnosis, it must be significant enough to interfere with social or occupational functioning.[24]

The four core clinical features (described in the Signs and symptoms section) are fluctuating cognition, visual hallucinations, REM sleep behavior disorder, and signs of parkinsonism. Supportive clinical features are marked sensitivity to antipsychotics; marked autonomic dysfunction; nonvisual hallucinations; hypersomnia; reduced ability to smell; false beliefs and delusions organized around a common theme; postural instability, loss of consciousness and frequent falls; and apathy, anxiety, or depression.

Direct laboratory-measurable biomarkers for DLB diagnosis are not known, but several indirect methods can lend further evidence for diagnosis.[24] The indicative diagnostic biomarkers are: reduced dopamine transporter uptake in the basal ganglia shown on PET or SPECT imaging; low uptake of 123iodine-metaiodobenzylguanidine (123I-MIBG) shown on myocardial scintigraphy; and loss of atonia during REM sleep evidenced on polysomnography. Supportive diagnostic biomarkers (from PET, SPECT, CT, or MRI brain imaging studies or EEG monitoring) are: lack of damage to medial temporal lobe; reduced occipital activity; and prominent slow-wave activity.[24]

Probable DLB can be diagnosed when dementia and at least two core features are present, or when one core feature and at least one indicative biomarker are present. Possible DLB can be diagnosed when dementia and only one core feature are present or, if no core features are present, then at least one indicative biomarker is present.[24]

DLB is distinguished from Parkinson's disease dementia by the time frame in which dementia symptoms appear relative to parkinsonian symptoms. DLB is diagnosed when cognitive symptoms begin before or at the same time as parkinsonian motor signs. Parkinson's disease dementia would be the diagnosis when Parkinson's disease is well established before the dementia occurs (the onset of dementia is more than a year after the onset of parkinsonian symptoms).[111]

DLB is listed in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5) as major or mild neurocognitive disorder with Lewy bodies. The differences between the DSM and DLB Consortium diagnostic criteria are: 1) the DSM does not include low dopamine transporter uptake as a supportive feature, and 2) unclear diagnostic weight is assigned to biomarkers in the DSM. Lewy body dementias are classified by the World Health Organization in its ICD-10, the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, in chapter VI, as diseases of the nervous system, code 31.8.

Clinical history and testing

Diagnostic tests can be used to establish some features of the condition and distinguish them from symptoms of other conditions. Diagnosis may include taking the person's medical history, a physical exam, assessment of neurological function, testing to rule out conditions that may cause similar symptoms, brain imaging, neuropsychological testing to assess cognitive function, sleep studies, or myocardial scintigraphy.[24] Laboratory testing can rule out other conditions that can cause similar symptoms, such as abnormal thyroid function, syphilis, HIV, or vitamin deficiencies that may cause symptoms similar to dementia.

Dementia screening tests are the Mini-Mental State Examination and the Montreal Cognitive Assessment. For tests of attention, digit span, serial sevens, and spatial span can be used for simple screening, and the Revised Digit Symbol Subtest of the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale may show defects in attention that are characteristic of DLB. The Frontal Assessment Battery, Stroop test and Wisconsin Card Sorting Test are used for evaluation of executive function, and there are many other screening instruments available.

If DLB is suspected when parkinsonism and dementia are the only presenting features, PET or SPECT imaging may show reduced dopamine transporter activity. A DLB diagnosis may be warranted if other conditions with reduced dopamine transporter uptake can be ruled out.[24]

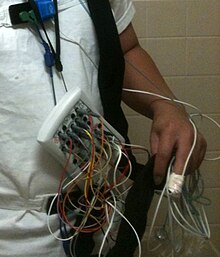

RBD is diagnosed either by sleep study recording or, when sleep studies cannot be performed, by medical history and validated questionnaires.[24] In individuals with dementia and a history of RBD, a probable DLB diagnosis can be justified (even with no other core feature or biomarker) based on a sleep study showing REM sleep without atonia because it is so highly predictive.[24] Conditions similar to RBD, like severe sleep apnea and periodic limb movement disorder, must be ruled out.[24] Prompt evaluation and treatment of RBD is indicated when a prior history of violence or injury is present as it may increase the likelihood of future violent dream enactment behaviors. Individuals with RBD may not be able to provide a history of dream enactment behavior, so bed partners are also consulted.[24] The REM Sleep Behavior Disorder Single-Question Screen offers diagnostic sensitivity and specificity in the absence of polysomnography with one question: "Have you ever been told, or suspected yourself, that you seem to 'act out your dreams' while asleep (for example, punching, flailing your arms in the air, making running movements, etc.)?"[117] Because some individuals with DLB do not have RBD, normal findings from a sleep study can not rule out DLB.

Since 2001, 123iodine-metaiodobenzylguanidine (123I-MIBG) myocardial scintigraphy has been used diagnostically in East Asia (principally Japan), but not in the United States.[32] MIBG is taken up by sympathetic nerve endings, such as those that innervate the heart, and is labeled for scintigraphy with radioactive 123iodine. Autonomic dysfunction resulting from damage to nerves in the heart in patients with DLB is associated with lower cardiac uptake of 123I-MIBG.

There is no genetic test to determine if an individual will develop DLB[24] and, according to the Lewy Body Dementia Association, genetic testing is not routinely recommended because there are only rare instances of hereditary DLB.

Differential

Many neurodegenerative conditions share cognitive and motor symptoms with dementia with Lewy bodies. The differential diagnosis includes Alzheimer's disease; such synucleinopathies as Parkinson's disease dementia, Parkinson's disease, and multiple system atrophy; vascular dementia; and progressive supranuclear palsy, corticobasal degeneration, and corticobasal syndrome.

The symptoms of DLB are easily confused with delirium, or more rarely as psychosis; prodromal subtypes of delirium-onset DLB and psychiatric-onset DLB have been proposed. Mismanagement of delirium is a particular concern because of the risks to people with DLB associated with antipsychotics. A careful examination for features of DLB is warranted in individuals with unexplained delirium. PET or SPECT imaging showing reduced dopamine transporter uptake can help distinguish DLB from delirium.

Lewy pathology affects the peripheral autonomic nervous system; autonomic dysfunction is observed less often in AD, frontotemporal, or vascular dementias, so its presence can help differentiate them. MRI scans almost always show abnormalities in the brains of people with vascular dementia, which can begin suddenly.

Alzheimer's disease

DLB is distinguishable from AD even in the prodromal phase. Short-term memory impairment is seen early in AD and is a prominent feature, while fluctuating attention is uncommon; impairment in DLB is more often seen first as fluctuating cognition. In contrast to AD—in which the hippocampus is among the first brain structures affected, and episodic memory loss related to encoding of memories is typically the earliest symptom—memory impairment occurs later in DLB. People with amnestic mild cognitive impairment (in which memory loss is the main symptom) may progress to AD, whereas those with non-amnestic mild cognitive impairment (which has more prominent impairments in language, visuospatial, and executive domains) are more likely to progress towards DLB. Memory loss in DLB has a different progression from AD because frontal structures are involved earlier, with later involvement of temporoparietal brain structures. Verbal memory is not as severely affected as in AD.

While 74% of people with autopsy-confirmed DLB had deficits in planning and organization, they show up in only 45% of people with AD. Visuospatial processing deficits are present in most individuals with DLB, and they show up earlier and are more pronounced than in AD. Hallucinations typically occur early in the course of DLB, are less common in early AD, but usually occur later in AD. AD pathology frequently co-occurs in DLB, so the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) testing for Aβ and tau protein that is often used to detect AD is not useful in differentiating AD and DLB.

PET or SPECT imaging can be used to detect reduced dopamine transporter uptake and distinguish AD from DLB. Severe atrophy of the hippocampus is more typical of AD than DLB. Before dementia develops (during the mild cognitive impairment phase), MRI scans show normal hippocampal volume. After dementia develops, MRI shows more atrophy among individuals with AD, and a slower reduction in volume over time among people with DLB than those with AD. Compared to people with AD, FDG-PET brain scans in people with DLB often show a cingulate island sign.

In East Asia, particularly Japan,123I-MIBG is used in the differential diagnosis of DLB and AD, because reduced labeling of cardiac nerves is seen only in Lewy body disorders. Other indicative and supportive biomarkers are useful in distinguishing DLB and AD (preservation of medial temporal lobe structures, reduced occipital activity, and slow-wave EEG activity).[24]

Synucleinopathies

Dementia with Lewy bodies and Parkinson's disease dementia are clinically similar after dementia occurs in Parkinson's disease. Delusions in Parkinson's disease dementia are less common than in DLB, and persons with Parkinson's disease are typically less caught up in their visual hallucinations than those with DLB. There is a lower incidence of tremor at rest in DLB than in Parkinson's disease, and signs of parkinsonism in DLB are more symmetrical. In multiple system atrophy, autonomic dysfunction appears earlier and is more severe, and is accompanied by uncoordinated movements, while visual hallucinations and fluctuating cognition are less common than in DLB. Urinary difficulty is one of the earliest symptoms with multiple system atrophy, and is often severe.

Frontotemporal dementias

Corticobasal syndrome, corticobasal degeneration and progressive supranuclear palsy are frontotemporal dementias with features of parkinsonism and impaired cognition. Similar to DLB, imaging may show reduced dopamine transporter uptake. Corticobasal syndrome and degeneration, and progressive supranuclear palsy, are usually distinguished from DLB by history and examination. Motor movements in corticobasal syndrome are asymmetrical. There are differences in posture, gaze and facial expressions in the most common variants of progressive supranuclear palsy, and falling backwards is more common relative to DLB. Visual hallucinations and fluctuating cognition are unusual in corticobasal degeneration and progressive supranuclear palsy.

Management

Palliative care is offered to ameliorate symptoms, but there are no medications that can slow, stop, or improve the relentless progression of the disease. No medications for DLB are approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration as of 2020, although donepezil is licensed in Japan and the Philippines for the treatment of DLB. As of 2020, there has been little study on the best management for non-motor symptoms such as sleep disorders and autonomic dysfunction; most information on management of autonomic dysfunction in DLB is based on studies of people with Parkinson's disease.[142]

Management can be challenging because of the need to balance treatment of different symptoms: cognitive dysfunction, neuropsychiatric features, impairments related to the motor system, and other nonmotor symptoms. Individuals with DLB have widely different symptoms that fluctuate over time, and treating one symptom can worsen another; suboptimal care can result from a lack or coordination among the physicians treating different symptoms.[142] A multidisciplinary approach—going beyond early and accurate diagnosis to include educating and supporting the caregivers—is favored.[9][144]

Medication

—B.P. Boot (2015), Comprehensive treatment of dementia with Lewy bodies[58]

Pharmacological management of DLB is complex because of adverse effects to medications and the wide range of symptoms