Tropical Disease

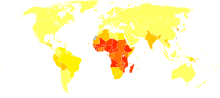

Tropical diseases are diseases that are prevalent in or unique to tropical and subtropical regions. The diseases are less prevalent in temperate climates, due in part to the occurrence of a cold season, which controls the insect population by forcing hibernation. However, many were present in northern Europe and northern America in the 17th and 18th centuries before modern understanding of disease causation. The initial impetus for tropical medicine was to protect the health of colonial settlers, notably in India under the British Raj. Insects such as mosquitoes and flies are by far the most common disease carrier, or vector. These insects may carry a parasite, bacterium or virus that is infectious to humans and animals. Most often disease is transmitted by an insect "bite", which causes transmission of the infectious agent through subcutaneous blood exchange. Vaccines are not available for most of the diseases listed here, and many do not have cures.

Human exploration of tropical rainforests, deforestation, rising immigration and increased international air travel and other tourism to tropical regions has led to an increased incidence of such diseases to non-tropical countries.

Health programmes

In 1975 the Special Programme for Research and Training in Tropical Diseases (TDR) was established to focus on neglected infectious diseases which disproportionately affect poor and marginalized populations in developing regions of Africa, Asia, Central America and North South America. It was established at the World Health Organization, which is the executing agency, and is co-sponsored by the United Nations Children's Fund, United Nations Development Programme, the World Bank and the World Health Organization.

TDR's vision is to foster an effective global research effort on infectious diseases of poverty in which disease endemic countries play a pivotal role. It has a dual mission of developing new tools and strategies against these diseases, and to develop the research and leadership capacity in the countries where the diseases occur. The TDR secretariat is based in Geneva, Switzerland, but the work is conducted throughout the world through many partners and funded grants.

Some examples of work include helping to develop new treatments for diseases, such as ivermectin for onchocerciasis (river blindness); showing how packaging can improve use of artemesinin-combination treatment (ACT) for malaria; demonstrating the effectiveness of bednets to prevent mosquito bites and malaria; and documenting how community-based and community-led programmes increases distribution of multiple treatments. TDR history

The current TDR disease portfolio includes the following entries:

| Disease | When added | Pathogen | Primary vector | Primary endemic areas | Frequency | Annual deaths | Symptoms | Complications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Malaria | 1975 | Plasmodium falciparum and four other Plasmodium species of protazoa | Anopheles mosquitoes | throughout the tropics | 228 million (2018) | 405,000 (2018) | fever, tiredness, vomiting, headache | yellow skin, seizures, coma, death |

| Schistosomiasis /ˌʃɪstəsəˈmaɪəsɪs/ (snail fever, bilharzia, "schisto") | 1975 | Schistosoma flatworms (blood flukes) | freshwater snails | throughout the tropics | 252 million (2015) | 4,400–200,000 | abdominal pain, diarrhea, bloody stool, blood in the urine. In children, it may cause poor growth and learning difficulty. | Liver damage, kidney failure, infertility, bladder cancer |

| Lymphatic filariasis | 1975 | Wuchereria bancrofti, Brugia malayi, and Brugia timori filarial worms | mosquitoes | throughout the tropics | 38.5 million (2015) | few | lymphoedema, elephantiasis, hydrocele | |

| Onchocerciasis /ˌɒŋkoʊsɜːrˈkaɪəsɪs, -ˈsaɪ-/ (river blindness) | 1975 | Onchocerca volvulus filarial worms | Simuliidae black flies | sub-Saharan Africa | 15.5 million (2015) | 0 | itching, papules | edema, lymphadenopathy, visual impairment, blindness |

| Chagas disease (American trypanosomiasis) | 1975 | Trypanosoma cruzi protozoa | Triatominae kissing bugs | South America | 6.2 million (2017) | 7,900 (2017) | fever, swollen lymph nodes, headache | heart failure, enlarged esophagus, enlarged colon |

| African trypanosomiasis (sleeping sickness) | 1975 | Trypanosoma brucei gambiense and T. b. rhodesiense protozoa | Glossina tsetse flies | sub-Saharan Africa | 11,000 (2015) | 3,500 (2015) | first stage: fever, headache, itchiness, joint pain

second stage: insomnia, confusion, ataxia, hemiparesis, paralysis |

anemia, endocrine disfunction, cardiac disfunction, kidney dysfunction, coma, death |

| Leishmaniasis | 1975 | Leishmania protozoa | Phlebotominae sandflies | throughout the tropics | 4–12 million | 24,200 (2015) | skin ulcers | fever, anemia, enlarged liver, enlarged spleen, death |

| Leprosy† (Hansen's disease) | 1975 | Mycobacterium leprae and M. lepromatosis mycobacteria | extensive contact (probably airborne disease) | throughout the tropics | 209,000 (2018) | few | skin lesions, numbness | permanent damage to the skin, nerves, limbs, and eyes |

| Dengue fever | 1999 | dengue virus | Aedes aegypti and other Aedes mosquitoes | tropical Asia | 390 million (2020) | 40,000 | fever, headache, muscle and joint pain, rash, vomiting, diarrhea | low levels of blood platelets, hypotension, hemorrhage, shock |

| Tuberculosis† (TB, consumption) | 1999 | Mycobacterium tuberculosis mycobacteria | airborne disease | worldwide | 10 million (active, 2018),

2 billion (latent, 2018) |

1.5 million (2018) | chronic cough, fever, cough with bloody mucus, weight loss | death |

| TB-HIV coinfection‡ | 1999 | HIV + Mycobacterium tuberculosis | sexual contact + airborne disease | Africa | 1.2 million (2015) | 251,000 (2018) | ||

| Sexually transmitted infections (notably syphilis, gonorrhoea, chlamydia, trichomoniasis, hepatitis B, HSV, HIV, and HPV) | 2000 | bacteria, parasite, viruses | sexual contact | worldwide | various | various |

- † Although leprosy and tuberculosis are not exclusively tropical diseases, their high incidence in the tropics justifies their inclusion.

- ‡ People living with HIV are 19 (15-22) times more likely to develop active TB disease than people without HIV.

Other neglected tropical diseases

Additional neglected tropical diseases include:

| Disease | Causative Agent | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| Hookworm | Ancylostoma duodenale and Necator americanus | |

| Trichuriasis | Trichuris trichiura | |

| Treponematoses | Treponema pallidum pertenue, Treponema pallidum endemicum, Treponema pallidum carateum, Treponema pallidum pallidum | |

| Buruli ulcer | Mycobacterium ulcerans | |

| Dracunculiasis | Dracunculus medinensis | |

| Leptospirosis | Leptospira | |

| Strongyloidiasis | Strongyloides stercoralis | |

| Foodborne trematodiases | Trematoda | |

| Neurocysticercosis | Taenia solium | |

| Scabies | Sarcoptes scabiei | |

| Flavivirus Infections | Yellow fever virus, West Nile virus, dengue virus, Tick-borne encephalitis virus, Zika virus |

Some tropical diseases are very rare, but may occur in sudden epidemics, such as the Ebola hemorrhagic fever, Lassa fever and the Marburg virus. There are hundreds of different tropical diseases which are less known or rarer, but that, nonetheless, have importance for public health.

Relation of climate to tropical diseases

The so-called "exotic" diseases in the tropics have long been noted both by travelers, explorers, etc., as well as by physicians. One obvious reason is that the hot climate present during all the year and the larger volume of rains directly affect the formation of breeding grounds, the larger number and variety of natural reservoirs and animal diseases that can be transmitted to humans (zoonosis), the largest number of possible insect vectors of diseases. It is possible also that higher temperatures may favor the replication of pathogenic agents both inside and outside biological organisms. Socio-economic factors may be also in operation, since most of the poorest nations of the world are in the tropics. Tropical countries like Brazil, which have improved their socio-economic situation and invested in hygiene, public health and the combat of transmissible diseases have achieved dramatic results in relation to the elimination or decrease of many endemic tropical diseases in their territory.

Climate change, global warming caused by the greenhouse effect, and the resulting increase in global temperatures, are possibly causing tropical diseases and vectors to spread to higher altitudes in mountainous regions, and to higher latitudes that were previously spared, such as the Southern United States, the Mediterranean area, etc. For example, in the Monteverde cloud forest of Costa Rica, global warming enabled Chytridiomycosis, a tropical disease, to flourish and thus force into decline amphibian populations of the Monteverde Harlequin frog. Here, global warming raised the heights of orographic cloud formation, and thus produced cloud cover that would facilitate optimum growth conditions for the implicated pathogen, B. dendrobatidis.

Prevention and treatment

Vector-borne diseases

Vectors are living organisms that pass disease between humans or from animal to human. The vector carrying the highest number of diseases is the mosquito, which is responsible for the tropical diseases dengue and malaria. Many different approaches have been taken to treat and prevent these diseases. NIH-funded research has produced genetically modify mosquitoes that are unable to spread diseases such as malaria. An issue with this approach is global accessibility to genetic engineering technology; Approximately 50% of scientists in the field do not have access to information on genetically modified mosquito trials being conducted.

Other prevention methods include:

- Draining wetlands to reduce populations of insects and other vectors, or introducing natural predators of the vectors.

- The application of insecticides and/or insect repellents) to strategic surfaces such as clothing, skin, buildings, insect habitats, and bed nets.

- The use of a mosquito net over a bed (also known as a "bed net") to reduce nighttime transmission, since certain species of tropical mosquitoes feed mainly at night.

Sexually transmitted diseases

Both pharmacologic pre-exposure prophylaxis (to prevent disease before exposure to the environment and/or vector) and pharmacologic post-exposure prophylaxis (to prevent disease after exposure to the environment and/or vector) are used to prevent and treat HIV

Community approaches

Assisting with economic development in endemic regions can contribute to prevention and treatment of tropical diseases. For example, microloans enable communities to invest in health programs that lead to more effective disease treatment and prevention technology.

Educational campaigns can aid in the prevention of various diseases. Educating children about how diseases spread and how they can be prevented has proven to be effective in practicing preventative measures. Educational campaigns can yield significant benefits at low costs.

Other approaches

- Use of water wells, and/or water filtration, water filters, or water treatment with water tablets to produce drinking water free of parasites.

- Sanitation to prevent transmission through human waste.

- Development and use of vaccines to promote disease immunity.

- Pharmacologic treatment (to treat disease after infection or infestation).

See also

- Hospital for Tropical Diseases

- Tropical medicine

- Infectious disease

- Neglected diseases

- List of epidemics

- Waterborne diseases

- Globalization and disease