Leber Congenital Amaurosis 14

A number sign (#) is used with this entry because of evidence that Leber congenital amaurosis-14 (LCA14) is caused by homozygous mutation in the LRAT gene (604863) on chromosome 4q32.

Mutation in the LRAT gene can also cause juvenile retinitis pigmentosa and a form of early-onset severe retinal dystrophy.

DescriptionAutosomal recessive childhood-onset severe retinal dystrophy is a heterogeneous group of disorders affecting rod and cone photoreceptors simultaneously. The most severe cases are termed Leber congenital amaurosis, whereas the less aggressive forms are usually considered juvenile retinitis pigmentosa (Gu et al., 1997).

For a general phenotypic description and a discussion of genetic heterogeneity of Leber congenital amaurosis, see LCA1 (204000); for retinitis pigmentosa, see 268000.

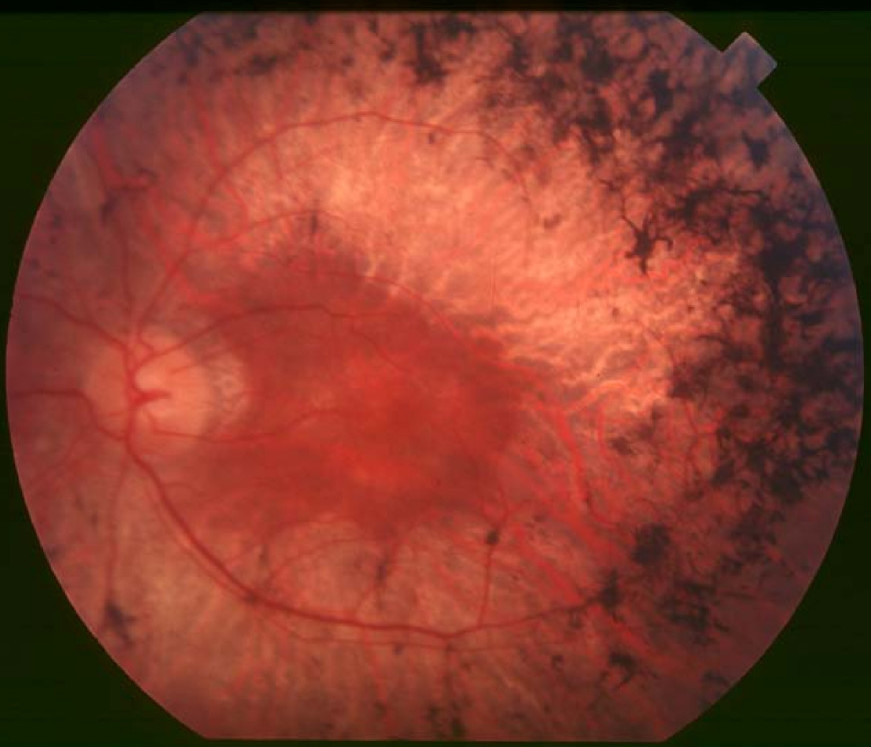

Clinical FeaturesThompson et al. (2001) studied 3 patients with early-onset severe retinal dystrophy. Two were female patients who had night blindness and poor vision in childhood and were diagnosed with retinitis pigmentosa (RP) at 2 years and 7 years of age, respectively. One had a visual field of less than 5 degrees, whereas the other had a visual field restricted to tiny central islands; in the latter patient, funduscopic examination showed optic disc pallor, attenuated retinal arterioles, peripheral retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) atrophy, and perimacular retinal surface wrinkling but little bone-spicule pigment. The third patient was a man who had nystagmus and was diagnosed with retinal degeneration at 3 years of age. He had no electroretinogram (ERG) responses at age 15 and at age 25 had no central vision.

Senechal et al. (2006) reported a boy with an 'RPE65 phenotype' (see LCA2, 204100), who had severe visual impairment and did not follow objects in infancy but could follow lights. He had no nystagmus but was profoundly night-blind. He progressively improved so that he recognized various objects and could move by himself in a bright environment at age 21 months. Examination revealed normal-appearing maculas with good reflexes and normal optic discs; there was no pigment deposit in the posterior pole or periphery, but retinal vessels were slightly narrowed. There were no depigmentation spots or flecks. The ERG was flat for all types of stimulation.

Den Hollander et al. (2007) described 2 unrelated French Canadian probands with retinal disease. The first was a woman diagnosed with Leber congenital amaurosis who had onset of disease noted at the age of 2 months, with night blindness and nystagmus but no photophobia. Funduscopic examination at 23 years of age showed normal RPE and retinal appearance in the posterior pole, then a sharp demarcation to an area with significant retinal hypopigmentation outside the arcades and to the periphery; Goldmann visual fields were 10 degrees with the V4e target. Over the next 10 years, she maintained hand motion vision, but her visual fields declined to 5 degrees, and she developed mild posterior subcapsular cataracts and a mild bull's eye maculopathy. The second proband and his affected sister, who were diagnosed with juvenile RP, presented with a history of night blindness from 2 years of age, poorly reactive pupils, and an accommodative esotropia. At 6 years of age, funduscopic examination in the boy showed a normal appearance at the posterior pole with sharp demarcation of the peripheral retina outside the arcades, with striking grainy (salt and pepper) retinal degeneration. Goldmann visual fields (V4e) were 75 degrees at age 7 years and 65 degrees at 9 years of age; visual acuity decreased from 20/70 OU to 20/100 OD and 20/200 OS over that period. His sister was very photophobic, with fine horizontal nystagmus and sluggish pupils. Retinal examination revealed pale optic discs, narrow blood vessels, and a marked translucency of the peripheral retina and RPE, with a grainy appearance. At 7 years of age, visual acuity was 20/150 and Goldmann visual fields (V4e) were 30 degrees.

Molecular GeneticsThompson et al. (2001) screened 267 retinal dystrophy patients for mutations in the LRAT gene and identified a missense mutation in 2 patients (S175R; 604863.0001) and a 2-bp deletion (604863.0002) in another patient; all 3 patients had severe, early-onset disease. Thompson et al. (2001) stated that their findings highlighted the importance of genetic defects in vitamin A metabolism as causes of retinal dystrophies and extended prospects for retinoid replacement therapy in this group of diseases.

In a 21-month-old boy who was diagnosed with Leber congenital amaurosis-2 (LCA2; 204100) but who was negative for mutation in the RPE65 gene (180069), Senechal et al. (2006) screened the LRAT gene and identified homozygosity for a 2-bp deletion (604863.0003). The unaffected first-cousin parents were heterozygous for the mutation, which was not found in 112 ethnically matched chromosomes. Senechal et al. (2006) noted that the 'early-onset severe retinal dystrophy' described by Thompson et al. (2001) in 3 patients with mutations in the LRAT gene (see 604863.0001 and 604863.0002) was compatible with the clinical description of this LCA patient.

In 2 unrelated French Canadian probands, 1 diagnosed with LCA and the other with juvenile RP, den Hollander et al. (2007) identified homozygosity for the same 2-bp deletion previously found by Senechal et al. (2006) in a French boy diagnosed with LCA. Den Hollander et al. (2007) suggested that the 2-bp deletion (217delAT) might represent a founder mutation originating from France.