Vertigo, Benign Recurrent

Benign recurrent vertigo (BRV1) has been mapped to chromosome 6p.

Another locus for benign recurrent vertigo has been identified on chromosome 22q12 (BRV2; 613106).

DescriptionBenign recurrent vertigo (BRV), also known as benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV), is a common disorder affecting up to 2% of the adult population. The majority of individuals with chronic recurrent vertigo have no identifiable cause, no progression of the disorder, and no other neurologic or auditory signs. Many families have multiple affected individuals, suggesting familial transmission of the disorder with moderate to high penetrance (summary by Lee et al., 2006).

Clinical FeaturesBaloh et al. (1994) described 3 patients who presented with episodic vertigo followed by gait imbalance and oscillopsia and were found to have profound bilateral vestibular loss despite normal hearing. All had a parent with similar findings. The patients, their affected parent, and multiple other family members had a history of migraine headaches, although several of the family members with migraine had normal vestibular function. Acetazolamide stopped or markedly decreased the frequency of vertigo attacks in the 3 patients treated, but had little affect on the chronic vestibular loss. The syndrome, referred to as Dandy syndrome by Belal (1980) and described by Dandy (1941), is characterized by the features reported here. Although some ototoxins, such as streptomycin and gentamicin, are relatively specific for the vestibular system, other causes of Dandy syndrome also produce severe bilateral hearing loss.

Wilmot (1998) suggested that familial vestibulopathy may be the same as episodic ataxia type 2 (EA2; 108500) and spinocerebellar ataxia-6 (SCA6; 183086), both of which are due to mutations in the calcium channel gene CACNA1A (601011).

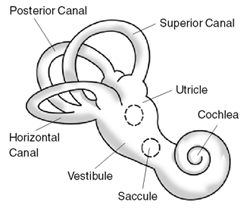

InheritanceBenign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV) is thought to be caused by dislodged otoconia from the utricular macula floating in the semicircular canals. At least half of BPPV cases are idiopathic. Experience with familial cases suggested to Gizzi et al. (1998) a genetic predisposition. They surveyed 120 successive BPPV patients and 120 successive dizzy patients without BPPV regarding the frequency of dizziness and BPPV (diagnosed by a physician) among family members. Patients in the BPPV group were 5 times as likely to have relatives with BPPV compared to the dizzy control group.

Oh et al. (2001) studied the families of 24 probands with benign recurrent vertigo who reported a family history of similar attacks of vertigo. The probands underwent a diagnostic evaluation to exclude identifiable causes. A questionnaire was sent to relatives of the probands. Of the 220 relatives responding, 37% reported benign recurrent vertigo, compared to 2% of unrelated spouses, and 50% met the criteria for migraine, compared to 23% of unrelated spouses. Of the first-degree relatives with benign recurrent vertigo, 73% were female. The authors concluded that the pedigrees were most consistent with autosomal dominant transmission of benign recurrent vertigo, with decreased penetrance in males.

MappingBy genomewide linkage analysis on 4 families with bilateral vestibulopathy, 3 of whom were reported by Baloh et al. (1994), Jen et al. (2004) identified a 24-cM region on chromosome 6q suggestive of linkage to the disorder (maximum multipoint parametric lod score of 2.9 at marker D6S1556). A small Swedish family with vestibulopathy (Brantberg, 2003) did not show linkage to this region, suggesting genetic heterogeneity.