Congenital Hyperinsulinism

Congenital hyperinsulinism is a condition that causes individuals to have abnormally high levels of insulin, which is a hormone that helps control blood sugar levels. People with this condition have frequent episodes of low blood sugar (hypoglycemia). In infants and young children, these episodes are characterized by a lack of energy (lethargy), irritability, or difficulty feeding. Repeated episodes of low blood sugar increase the risk for serious complications such as breathing difficulties, seizures, intellectual disability, vision loss, brain damage, and coma.

The severity of congenital hyperinsulinism varies widely among affected individuals, even among members of the same family. About 60 percent of infants with this condition experience a hypoglycemic episode within the first month of life. Other affected children develop hypoglycemia by early childhood. Unlike typical episodes of hypoglycemia, which occur most often after periods without food (fasting) or after exercising, episodes of hypoglycemia in people with congenital hyperinsulinism can also occur after eating.

Frequency

Congenital hyperinsulinism affects approximately 1 in 50,000 newborns. This condition is more common in certain populations, affecting up to 1 in 2,500 newborns.

Causes

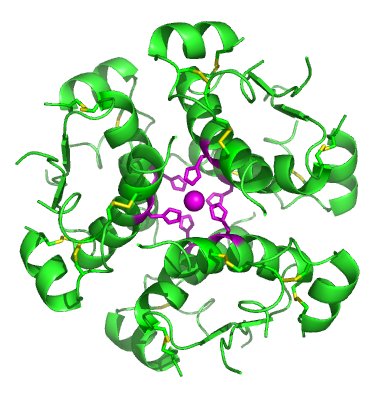

Congenital hyperinsulinism is caused by mutations in genes that regulate the release (secretion) of insulin, which is produced by beta cells in the pancreas. Insulin clears excess sugar (in the form of glucose) from the bloodstream by passing glucose into cells to be used as energy.

Gene mutations that cause congenital hyperinsulinism lead to over-secretion of insulin from beta cells. Normally, insulin is secreted in response to the amount of glucose in the bloodstream: when glucose levels rise, so does insulin secretion. However, in people with congenital hyperinsulinism, insulin is secreted from beta cells regardless of the amount of glucose present in the blood. This excessive secretion of insulin results in glucose being rapidly removed from the bloodstream and passed into tissues such as muscle, liver, and fat. A lack of glucose in the blood results in frequent states of hypoglycemia in people with congenital hyperinsulinism. Insufficient blood glucose also deprives the brain of its primary source of fuel.

Mutations in at least nine genes have been found to cause congenital hyperinsulinism. Mutations in the ABCC8 gene are the most common known cause of the disorder. They account for this condition in approximately 40 percent of affected individuals. Less frequently, mutations in the KCNJ11 gene have been found in people with congenital hyperinsulinism. Mutations in each of the other genes associated with this condition account for only a small percentage of cases.

In approximately half of people with congenital hyperinsulinism, the cause is unknown.

Learn more about the genes associated with Congenital hyperinsulinism

Additional Information from NCBI Gene:

Inheritance Pattern

Congenital hyperinsulinism can have different inheritance patterns, usually depending on the form of the condition. At least two forms of the condition have been identified. The most common form is the diffuse form, which occurs when all of the beta cells in the pancreas secrete too much insulin. The focal form of congenital hyperinsulinism occurs when only some of the beta cells over-secrete insulin.

Most often, the diffuse form of congenital hyperinsulinism is inherited in an autosomal recessive pattern, which means both copies of the gene in each cell have mutations. The parents of an individual with an autosomal recessive condition each carry one copy of the mutated gene, but they typically do not show signs and symptoms of the condition.

Less frequently, the diffuse form is inherited in an autosomal dominant pattern, which means one copy of the altered gene in each cell is sufficient to cause the disorder.

The inheritance of the focal form of congenital hyperinsulinism is more complex. For most genes, both copies are turned on (active) in all cells, but for a small subset of genes, one of the two copies is turned off (inactive). Most people with the focal form of this condition inherit one copy of the mutated, inactive gene from their unaffected father. During embryonic development, a mutation occurs in the other, active copy of the gene. This second mutation is found within only some cells in the pancreas. As a result, some pancreatic beta cells have abnormal insulin secretion, while other beta cells function normally.