Anti-Catholicism

- Traditional African religion

- Atheism

- Baháʼí Faith

- Buddhism

- Christianity

- Anti-Christian sentiment

- Anti-Catholicism

- Anti-Mormonism

- Anti-Jehovah's Witness

- Anti-Eastern Orthodox sentiment

- Anti-Oriental Orthodox sentiment

- Anti-Protestantism

- Falun Gong

- Hinduism (Hinduphobia)

- Islam

- Sunni

- Shi'a

- Ahmadiyya

- Alevism

- Sufis

- Islamophobia

- Judaism

- Religious antisemitism

- Antisemitism

- Anti-Judaism

- New religious movements

- Christian countercult movement

- Neopaganism

- Rastafari

- Zoroastrianism

Anti-Catholicism is hostility towards Catholics or opposition to the Catholic Church, its clergy, and/or its adherents. At various points after the Reformation, some majority Protestant states, including England, Prussia, and Scotland made anti-Catholicism and opposition to the Pope and Catholic rituals major political themes, and the anti-Catholic sentiment which resulted from it frequently lead to religious discrimination against Catholic individuals (often derogatorily referred to in Anglophone Protestant countries as "papists" or "Romanists"). Historian John Wolffe identifies four types of anti-Catholicism: constitutional-national, theological, popular and socio-cultural.

Historically, Catholics who lived in Protestant countries were frequently suspected of conspiring against the state in furtherance of papal interests. Support for the alien pope led to allegations that they lacked loyalty to the state. In majority Protestant countries with large scale immigration, such as the United States and Australia, suspicion of Catholic immigrants or discrimination against them often overlapped or was conflated with nativism, xenophobia, and ethnocentric or racist sentiments (i.e. anti-Italianism, anti-Irish sentiment, Hispanophobia, anti-French sentiment, anti-Quebec sentiment, anti-Polish sentiment).

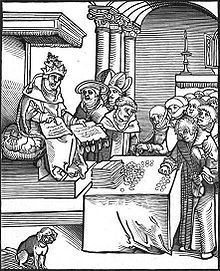

In the Early modern period, the Catholic Church struggled to maintain its traditional religious and political role in the face of rising secular powers in Catholic countries. As a result of these struggles, a hostile attitude towards the considerable political, social, spiritual and religious power of the Pope and the clergy arose in the form of anti-clericalism. The Inquisition was a favorite target of attack. Anti-clerical forces gained strength after 1789 in some primarily Catholic nations, such as France, Spain and Mexico. Political parties formed that expressed a hostile attitude towards the considerable political, social, spiritual and religious power of the Catholic Church in the form of anti-clericalism, attacks on the power of the pope to name bishops, and international orders, especially the Jesuits.

In primarily Protestant countries

Protestant Reformers, including John Wycliffe, Martin Luther, Henry VIII, John Calvin, Thomas Cranmer, John Thomas, John Knox, Roger Williams, Cotton Mather, and John Wesley, as well as most Protestants of the 16th-19th centuries, identified the Papacy with the Antichrist. The Centuriators of Magdeburg, a group of Lutheran scholars in Magdeburg headed by Matthias Flacius, wrote the 12-volume Magdeburg Centuries to discredit the Papacy and lead other Christians to recognize the Pope as the Antichrist. The fifth round of talks in the Lutheran–Catholic dialogue notes,

In calling the pope the "Antichrist", the early Lutherans stood in a tradition that reached back into the eleventh century. Not only dissidents and heretics but even saints had called the bishop of Rome the "Antichrist" when they wished to castigate his abuse of power. What Lutherans incorrectly understood as a papal claim to unlimited authority over everything and everyone reminded them of the Apocalyptic imagery of Daniel 11, a passage that had been applied to the pope as the Antichrist of the last days even prior to the Reformation.

Doctrinal works of literature published by the Lutherans, the Reformed churches, the Presbyterians, the Baptists, the Anabaptists, and the Methodists contain references to the Pope as the Antichrist, including the Smalcald Articles, Article 4 (1537), the Treatise on the Power and Primacy of the Pope (1537), the Westminster Confession, Article 25.6 (1646), and the 1689 Baptist Confession of Faith, Article 26.4. In 1754, John Wesley published his Explanatory Notes Upon the New Testament, which is currently an official Doctrinal Standard of the United Methodist Church. In his notes on the Book of Revelation (chapter 13), he commented: "The whole succession of Popes from Gregory VII are undoubtedly Antichrists. Yet this hinders not, but that the last Pope in this succession will be more eminently the Antichrist, the Man of Sin, adding to that of his predecessors a peculiar degree of wickedness from the bottomless pit."

Referring to the Book of Revelation, Edward Gibbon stated that "The advantage of turning those mysterious prophecies against the See of Rome, inspired the Protestants with uncommon veneration for so useful an ally." Protestants condemned the Catholic policy of mandatory celibacy for priests.

During the Enlightenment Era, which spanned the 17th and 18th centuries, with its strong emphasis on the need for religious toleration, the Inquisition was a favorite target of attack for intellectuals.

British Empire

Great Britain

Institutional anti-Catholicism in Britain and Ireland began with the English Reformation under Henry VIII. The Act of Supremacy of 1534 declared the English crown to be 'the only supreme head on earth of the Church in England' in place of the pope. Any act of allegiance to the latter was considered treasonous because the papacy claimed both spiritual and political power over its followers. It was under this act that saints Thomas More and John Fisher were executed and became martyrs to the Catholic faith.

Queen Mary, Henry's daughter, was a devout Catholic and during her five years as queen (1553–58) she tried to reverse the Reformation. She married the Catholic king of Spain and executed Protestant leaders. Protestants reviled her as "Bloody Mary".

Anti-Catholicism among many of the English was grounded in their fear that the pope sought to reimpose not just religio-spiritual authority over England but also secular power in alliance with their arch-enemy France or Spain. In 1570, Pope Pius V sought to depose Elizabeth with the papal bull Regnans in Excelsis, which declared her a heretic and purported to dissolve the duty of all Elizabeth's subjects of their allegiance to her. This rendered Elizabeth's subjects who persisted in their allegiance to the Catholic Church politically suspect, and made the position of her Catholic subjects largely untenable if they tried to maintain both allegiances at once. The Recusancy Acts, making it a legal obligation to worship in the Anglican faith, date from Elizabeth's reign.

Assassination plots in which Catholics were prime movers fueled anti-Catholicism in England. These included the famous Gunpowder Plot, in which Guy Fawkes and other conspirators plotted to blow up the English Parliament while it was in session. The fictitious "Popish Plot" involving Titus Oates was a hoax that many Protestants believed to be true, exacerbating Anglican-Catholic relations.

The Glorious Revolution of 1688–1689 involved the overthrow of King James II, of the Stuart dynasty, who favoured the Catholics, and his replacement by a Dutch Protestant. For decades the Stuarts were supported by France in plots to invade and conquer Britain, and anti-Catholicism persisted.

Gordon Riots 1780

The Gordon Riots of 1780 were a violent anti-Catholic protest in London against the Papists Act of 1778, which was intended to reduce official discrimination against British Catholics. Lord George Gordon, head of the Protestant Association warned that the law would enable Catholics in the British Army to become a dangerous threat. The protest evolved into riots and widespread looting. Local magistrates were afraid of reprisals and did not issue the riot act. There was no repression until the Army finally moved in and started shooting, killing hundreds of protesters. The main violence lasted from 2 June to 9 June 1780. Public opinion, especially in middle-class and elite circles, repudiated anti-Catholicism and lower-class violence, and rallied behind Lord North's government. Demands were made for a London police force.

19th century

The long bitter wars with France 1793–1815, saw anti-Catholicism emerge as the glue that held the three kingdoms together. From the upper classes to the lower classes, Protestants were brought together from England, Scotland and Ireland into a profound distrust and distaste for all things French. That enemy nation was depicted as the natural home of misery and oppression because of its inherent inability to shed the darkness of Catholic superstition and clerical manipulation.

Catholics in Ireland got the vote in the 1790s but were politically inert for another three decades. Finally, they were mobilized by Daniel O'Connell into majorities in most of the Irish parliamentary districts. They could only elect, but Catholics could not be seated in parliament. The Catholic emancipation issue became a major crisis. Previously anti-Catholic politicians led by the Duke of Wellington and Robert Peel reversed themselves to prevent massive violence. All Catholics in Britain were "emancipated" in the Roman Catholic Relief Act 1829. That is, they were freed from most of the penalties and restrictions they faced. Anti-Catholic attitudes continued, however.

Since 1945

Since World War II anti-Catholic feeling in England has abated somewhat. Ecumenical dialogue between Anglicans and Catholics culminated in the first meeting of an Archbishop of Canterbury with a Pope since the Reformation when Archbishop Geoffrey Fisher visited Rome in 1960. Since then, dialogue has continued through envoys and standing conferences. Meanwhile, both the nonconformist churches such as the Methodists, and the established Church of England, have dramatically declined in membership. Catholic membership in Britain continues to grow, thanks to the immigration of Irish and more recently Polish workers.

Conflict and rivalry between Catholicism and Protestantism since the 1920s, and especially since the 1960s, has centred on the Troubles in Northern Ireland.

Anti-Catholicism in Britain was long represented by the burning of an effigy of the Catholic conspirator Guy Fawkes at widespread celebrations on Guy Fawkes Night every 5 November. However, this celebration has lost most of its anti-Catholic connotations. Only faint remnants of anti-Catholicism are found today.

Ireland

As punishment for the rebellion of 1641, almost all lands owned by Irish Catholics were confiscated and given to Protestant settlers. Under the penal laws, no Irish Catholic could sit in the Parliament of Ireland, even though some 90% of Ireland's population was native Irish Catholic when the first of these bans was introduced in 1691. Catholic / Protestant strife has been blamed for much of "The Troubles", the ongoing struggle in Northern Ireland.

The English Protestant rulers killed many thousands of Irish people (mostly Catholics) who refused to acknowledge the government and sought an alliance with Catholic France, England's great enemy. General Oliver Cromwell, England's military dictator (1653–58) launched a full-scale military attack on Catholics in Ireland, (1649–53). Frances Stewart explains: "Faced with the prospect of an Irish alliance with Charles II, Cromwell carried out a series of massacres in order to subdue the Irish. Then, once Cromwell had returned to England, the English Commissary, General Henry Ireton adopted a deliberate policy of crop burning and starvation, which was responsible for the majority of an estimated 600,000 deaths out of a total Irish population of 1,400,000."

Laws that restricted the rights of Irish Catholics

The Great Famine of Ireland was due in part to Anti-Catholic laws. In the 17th and 18th centuries, Irish Catholics had been prohibited by the penal laws from purchasing or leasing land, from voting, from holding political office, from living in or within 5 miles (8 km) of a corporate town, from obtaining education, from entering a profession, and from doing many other things that were necessary for a person to succeed and prosper in society. The laws had largely been reformed by 1793, and in 1829, Irish Catholics could again sit in parliament following the Act of Emancipation.

Northern Ireland

The state of Northern Ireland came into existence in 1921, following the Government of Ireland Act 1920. Though Catholics were a majority on the island of Ireland, comprising 73.8% of the population in 1911, they were a third of the population in Northern Ireland.

In 1934, Sir James Craig, the first Prime Minister of Northern Ireland, said, "Since we took up office we have tried to be absolutely fair towards all the citizens of Northern Ireland... They still boast of Southern Ireland being a Catholic State. All I boast of is that we are a Protestant Parliament and a Protestant State."

In 1957, Harry Midgley, the Minister of Education in Northern Ireland, said, in Portadown Orange Hall, "All the minority are traitors and have always been traitors to the Government of Northern Ireland."

The first Catholic to be appointed a minister in Northern Ireland was Dr Gerard Newe, in 1971.

Canada

Fears of the Catholic Church were quite strong in the 19th century, especially among Presbyterian and other Protestant Irish immigrants across Canada.

In 1853, the Gavazzi Riots left 10 dead in Quebec in the wake of Catholic Irish protests against Anti-catholic speeches by ex-monk Alessandro Gavazzi. The most influential newspaper in Canada, The Globe of Toronto, was edited by George Brown, a Presbyterian immigrant from Ireland who ridiculed and denounced the Catholic Church, Jesuits, priests, nunneries, etc. Irish Protestants remained a political force until the 20th century. Many belonged to the Orange Order, an anti-Catholic organization with chapters across Canada that was most powerful during the late 19th century.

A key leader was Dalton McCarthy (1836–1898), a Protestant who had immigrated from Ireland. In the late 19th century he mobilized the "Orange" or Protestant Irish, and fiercely fought against Irish Catholics as well as the French Catholics. He especially crusaded for the abolition of the French language in Manitoba and Ontario schools.

French language schools in Canada

One of the most controversial issues was public support for Catholic French-language schools. Although the Confederation Agreement of 1867 guaranteed the status of Catholic schools when legalized by provincial governments, disputes erupted in numerous provinces, especially in the Manitoba Schools Question in the 1890s and in Ontario in the 1910s. In Ontario, Regulation 17 was a regulation by the Ontario Ministry of Education that restricted the use of French as a language of instruction to the first two years of schooling. French Canada reacted vehemently and lost, dooming its French-language Catholic schools. This was a central reason for French Canada's distance from the World War I effort, as its young men refused to enlist.

Protestant elements succeeded in blocking the growth of French-language Catholic public schools. However, the Irish Catholics generally supported the English language position advocated by the Protestants.

Newfoundland

Newfoundland long experienced social and political tensions between the large Irish Catholic working-class, on the one hand and the Anglican elite on the other. In the 1850s, the Catholic bishop organized his flock and made them stalwarts of the Liberal party. Nasty rhetoric was the prevailing style elections; bloody riots were common during the 1861 election. The Protestants narrowly elected Hugh Hoyles as the Conservative Prime Minister. Hoyles unexpectedly reversed his long record of militant Protestant activism and worked to defuse tensions. He shared patronage and power with the Catholics; all jobs and patronage were split between the various religious bodies on a per capita basis. This 'denominational compromise' was further extended to education when all religious schools were put on the basis which the Catholics had enjoyed since the 1840s. Alone in North America Newfoundland had a state funded system of denominational schools. The compromise worked and politics ceased to be about religion and became concerned with purely political and economic issues.

Australia

The presence of Catholicism in Australia came with the 1788 arrival of the First Fleet of British convict ships at Sydney. The colonial authorities blocked a Catholic clerical presence until 1820, reflecting the legal disabilities of Catholics in Britain. Some of the Irish convicts had been transported to Australia for political crimes or social rebellion and authorities remained suspicious of the minority religion.

Catholic convicts were compelled to attend Church of England services and their children and orphans were raised as Anglicans. The first Catholic priests to arrive came as convicts following the Irish 1798 Rebellion. In 1803, one Fr Dixon was conditionally emancipated and permitted to celebrate Mass, but following the Irish led Castle Hill Rebellion of 1804, Dixon's permission was revoked. Fr Jeremiah Flynn, an Irish Cistercian, was appointed as Prefect Apostolic of New Holland and set out uninvited from Britain for the colony. Watched by authorities, Flynn secretly performed priestly duties before being arrested and deported to London. Reaction to the affair in Britain led to two further priests being allowed to travel to the colony in 1820. The Church of England was disestablished in the Colony of New South Wales by the Church Act of 1836. Drafted by the Catholic attorney-general John Plunkett, the act established legal equality for Anglicans, Catholics and Presbyterians and was later extended to Methodists.

By the late 19th century approximately a quarter of the population of Australia were Irish Australians. Many were descended from the 40,000 Irish Catholics who were transported as convicts to Australia before 1867. The majority consisted of British and Irish Protestants. The Catholics dominated the labour unions and the Labor Party. The growth of school systems in the late 19th century typically involved religious issues, pitting Protestants against Catholics. The issue of independence for Ireland was long a sore point, until the matter was resolved by the Irish War of Independence.

Limited freedom of belief is protected by Section 116 of the Constitution of Australia, but sectarianism in Australia was prominent (though generally nonviolent) in the 20th century, flaring during the First World War, again reflecting Ireland's place within the Empire, and the Catholic minority remained subject to discrimination and suspicion. During the First World War, the Irish gave support for the war effort and comprised 20% of the army in France. However, the labour unions and the Irish in particular, strongly opposed conscription, and in alliance with like-minded farmers, defeated it in national plebiscites in 1916 and 1917. The Anglicans in particular talked of Catholic "disloyalty". By the 1920s, Australia had its first Catholic prime minister.

During the 1950s, the split in the Australian Labor Party between allies and opponents of the Catholic anti-Communist B.A. Santamaria meant that the party (in Victoria and Queensland more than elsewhere) was effectively divided between pro-Catholic and anti-Catholic elements. As a result of such disunity the ALP was defeated at every single national election between 1955 and 1972. In the late 20th century, the Catholic Church replaced the Anglican Church as the largest single Christian body in Australia; and it continues to be so in the 21st century, although it still has fewer members than do the various Protestant churches combined.

While older sectarian divides declined, commentators have observed a re-emergence of anti-Catholicism in Australia in recent decades amid rising secularism and broader anti-Christian movements.

New Zealand

According to New Zealand scholar Michael King, the situation in New Zealand has never been as clear as it was in Australia. Catholics first arrived in New Zealand in 1769. The Church has had "a continuous presence there from the time of the permanent settlement by Irish Catholics in the 1820s, and the first conversions of Maori in the 1830s." However the achievement of the English to gain Maori signatures to a "Treaty" in 1840, created a dominant Protestant country, though French Jean Baptiste Pompallier was able to include a clause about guaranteed freedom of religion in the text. Some sectarian violence was evident in New Zealand in the late 19th century and early twentieth.

In the 21st century, Catholicism expresses itself as a left-wing social movement, which includes Jim Anderton; however, other children of established Catholic families have entered politics, where they tend to join right-wing individualist forces (Jim Bolger, Peter Dunne, Gerry Brownlee). King notes (p. 183) that Bolger (centre-right wing National Party) was the country's fourth Catholic Prime Minister. A previous Catholic Prime Minister was Michael Joseph Savage, who instigated numerous social reforms, evidence that since the 1930s, Catholics have been more at odds within their own ranks, than discriminated against in New Zealand society.

German Empire

Unification into the German Empire in 1871 saw a country with a Protestant majority and large Catholic minority, speaking German or Polish. Anti-Catholicism was common. The powerful German Chancellor Otto von Bismarck—a devout Lutheran—forged an alliance with secular liberals in 1871–1878 to launch a Kulturkampf (literally, "culture struggle") especially in Prussia, the largest state in the new German Empire to destroy the political power of the Catholic Church and the Pope. Catholics were numerous in the South (Bavaria, Baden-Wuerttemberg) and west (Rhineland) and fought back. Bismarck intended to end Catholics' loyalty with Rome (ultramontanism) and subordinate all Germans to the power of his state.

Priests and bishops who resisted the Kulturkampf were arrested or removed from their positions. By the height of anti-Catholic legislation, half of the Prussian bishops were in prison or in exile, a quarter of the parishes had no priest, half the monks and nuns had left Prussia, a third of the monasteries and convents were closed, 1800 parish priests were imprisoned or exiled, and thousands of laymen were imprisoned for helping the priests. There were anti-Polish elements in Greater Poland Silesia. The Catholics refused to comply; they strengthened their Centre Party.

Pius IX died in 1878 and was replaced by more conciliatory Pope Leo XIII who negotiated away most of the anti-Catholic laws beginning in 1880. Bismark himself broke with the anti-Catholic Liberals and worked with the Catholic Centre Party to fight Socialism. Pope Leo officially declared the end of the Kulturkampf on 23 May 1887.

Nazi Germany

The Catholic Church faced repression in Nazi Germany (1933-1945). Hitler despised the Church although he had been brought up in a Catholic home. The long-term aim of the Nazis was to de-Christianise Germany and restore Germanic paganism. Richard J. Evans writes that Hitler believed that in the long run National Socialism and religion would not be able to co-exist, and he stressed repeatedly that Nazism was a secular ideology, founded on modern science: "Science, he declared, would easily destroy the last remaining vestiges of superstition". Germany could not tolerate the intervention of foreign influences such as the Pope and "Priests, he said, were 'black bugs', 'abortions in black cassocks'". Nazi ideology desired the subordination of the Church to the State and could not accept an autonomous establishment, whose legitimacy did not spring from the government. From the beginning, the Catholic Church faced general persecution, regimentation and oppression. Aggressive anti-Church radicals like Joseph Goebbels and Martin Bormann saw the conflict with the Churches as a priority concern, and anti-Church and anti-clerical sentiments were strong among grassroots party activists. To many Nazis, Catholics were suspected of insufficient patriotism, or even of disloyalty to the Fatherland, and of serving the interests of "sinister alien forces".

Adolf Hitler had some regard for the organisational power of Catholicism, but towards its teachings he showed nothing but the sharpest hostility, calling them "the systematic cultivation of the human failure": To Hitler, Christianity was a religion that was only fit for slaves and he detested its ethics. Alan Bullock wrote: "Its teaching, he declared, was a rebellion against the natural law of selection by struggle and the survival of the fittest". For political reasons, Hitler was prepared to restrain his anti-clericalism, seeing danger in strengthening the Church by persecuting it, but he intended to wage a show-down against it after the war. Joseph Goebbels, the Minister for Propaganda, led the Nazi persecution of the Catholic clergy and wrote that there was "an insoluble opposition between the Christian and a heroic-German world view". Hitler's chosen deputy, Martin Bormann, was a rigid guardian of Nazi orthodoxy and saw Christianity and Nazism as "incompatible", as did the official Nazi philosopher, Alfred Rosenberg, who wrote in Myth of the Twentieth Century (1930) that Catholics were among the chief enemies of the Germans. In 1934, the Sanctum Officium put Rosenberg's book on the Index Librorum Prohibitorum (forbidden books list of the Church) for scorning and rejecting "all dogmas of the Catholic Church, indeed the very fundamentals of the Christian religion".

The Nazis claimed jurisdiction over all collective and social activity, interfering with Catholic schooling, youth groups, workers' clubs and cultural societies. Hitler moved quickly to eliminate Political Catholicism, rounding up members of the Catholic aligned Bavarian People's Party and Catholic Centre Party, which ceased to exist in early July 1933. Vice Chancellor Papen meanwhile, amid continuing molestation of Catholic clergy and organisations, negotiated a Reich concordat with the Holy See, which prohibited clergy from participating in politics. Hitler then proceeded to close all Catholic institutions whose functions weren't strictly religious:

It quickly became clear that [Hitler] intended to imprison the Catholics, as it were, in their own churches. They could celebrate Mass and retain their rituals as much as they liked, but they could have nothing at all to do with German society otherwise. Catholic schools and newspapers were closed, and a propaganda campaign against the Catholics was launched.

— Extract from An Honourable Defeat by Anton Gill

Almost immediately after agreeing the Concordat, the Nazis promulgated their sterilization law, an offensive policy in the eyes of the Catholic Church and moved to dissolve the Catholic Youth League. Clergy, nuns and lay leaders began to be targeted, leading to thousands of arrests over the ensuing years, often on trumped up charges of currency smuggling or "immorality". In Hitler's Night of the Long Knives purge, Erich Klausener, the head of Catholic Action, was assassinated. Adalbert Probst, national director of the Catholic Youth Sports Association, Fritz Gerlich, editor of Munich's Catholic weekly and Edgar Jung, one of the authors of the Marburg speech, were among the other Catholic opposition figures killed in the purge.

By 1937, the Church hierarchy in Germany, which had initially attempted to co-operate with the new government, had become highly disillusioned. In March, Pope Pius XI issued the Mit brennender Sorge encyclical - accusing the Nazis of violations of the Concordat, and of sowing the "tares of suspicion, discord, hatred, calumny, of secret and open fundamental hostility to Christ and His Church". The Pope noted on the horizon the "threatening storm clouds" of religious wars of extermination over Germany. The Nazis responded with, an intensification of the Church Struggle. There were mass arrests of clergy and Church presses were expropriated. Goebbels renewed the regime's crackdown and propaganda against Catholics. By 1939 all Catholic denominational schools had been disbanded or converted to public facilities. By 1941, all Church press had been banned.

Later Catholic protests included the 22 March 1942 pastoral letter by the German bishops on "The Struggle against Christianity and the Church". About 30 per cent of Catholic priests were disciplined by police during the Nazi era. In effort to counter the strength and influence of spiritual resistance, the security services monitored Catholic clergy very closely - instructing that agents monitor every diocese, that the bishops' reports to the Vatican should be obtained and that bishops' activities be discovered and reported. Priests were frequently denounced, arrested, or sent to concentration camps – many to the dedicated clergy barracks at Dachau. Of a total of 2,720 clergy imprisoned at Dachau, some 2,579 (or 94.88%) were Catholic. Nazi policy towards the Church was at its most severe in the territories it annexed to Greater Germany, where the Nazis set about systematically dismantling the Church - arresting its leaders, exiling its clergymen, closing its churches, monasteries and convents. Many clergymen were murdered.

Netherlands

The independence of the Netherlands from Spanish rule saw a majority Protestant country of Calvinist nature. In Amsterdam Catholic priests were driven out of the city, and Following the Dutch takeover, all churches were converted to Protestant worship, Only in the 20th century was Amsterdam's relation to Catholicism normalised.

Nordic countries

Norway

After the dissolution of Denmark-Norway in 1814, the new Norwegian Constitution of 1814, did not grant religious freedom, as it stated that both Jews and Jesuits were denied entrance to the Kingdom of Norway. It also stated that attendance in a Lutheran church was compulsory, effectively banning Catholics. The ban on Catholicism was lifted in 1842, and the ban on Jews was lifted in 1851. At first, there were multiple restrictions on the practice of Catholicism and only foreign citizens were allowed to practice. The first post-reformation parish was founded in 1843, Catholics were only allowed to celebrate Mass in this one parish. In 1845 most restrictions on non-Lutheran Christianity were lifted, and Catholics were now allowed to practice their religion freely, but Monasticism and Jesuits were first allowed as late as 1897 and 1956 respectively.

United States

John Higham described anti-Catholicism as "the most luxuriant, tenacious tradition of paranoiac agitation in American history".

- Jenkins, Philip. The New Anti-Catholicism: The Last Acceptable Prejudice (Oxford University Press, New ed. 2004). British anti-Catholicism was exported to the United States. Two types of anti-Catholic rhetoric existed in colonial society. The first, derived from the heritage of the Protestant Reformation and the religious wars of the sixteenth century, consisted of the "Anti-Christ" and the "Whore of Babylon" variety and it dominated Anti-Catholic thought until the late seventeenth century. The second was a more secular variety which focused on the supposed intrigue of the Catholics intent on extending medieval despotism worldwide.

Historian Arthur Schlesinger Sr. has called Anti-Catholicism "the deepest-held bias in the history of the American people".

Historian Joseph G. Mannard says that wars reduced anti-Catholicism: "enough Catholics supported the War for Independence to erase many old myths about the inherently treasonable nature of Catholicism....During the Civil War the heavy enlistments of Irish and Germans into the Union Army helped to dispel notions of immigrant and Catholic disloyalty."

Colonial era

American anti-Catholicism has its origins in the Protestant Reformation which generated anti-Catholic propaganda for various political and dynastic reasons. Because the Protestant Reformation justified itself as an effort to correct what it perceived were the errors and the excesses of the Catholic Church, it formed strong positions against the Catholic bishops and the Papacy in particular. These positions were brought to New England by English colonists who were predominantly Puritans. They opposed not only the Catholic Church but also the Church of England which, due to its perpetuation of some Catholic doctrines and practices, was deemed insufficiently "reformed". Furthermore, English and Scottish identity to a large extent was based on opposition to Catholicism. "To be English was to be anti-Catholic," writes Robert Curran.

Because many of the British colonists, such as the Puritans and Congregationalists, were fleeing religious persecution by the Church of England, much of early American religious culture exhibited the more extreme anti-Catholic bias of these Protestant denominations. Monsignor John Tracy Ellis wrote that a "universal anti-Catholic bias was brought to Jamestown in 1607 and vigorously cultivated in all the thirteen colonies from Massachusetts to Georgia". Colonial charters and laws often contained specific proscriptions against Catholics. For example, the second Massachusetts charter of October 7, 1691, decreed "that forever hereafter there shall be liberty of conscience allowed in the worship of God to all Christians, except Papists, inhabiting, or which shall inhabit or be resident within, such Province or Territory". Historians have identified only one Catholic living in colonial Boston--Ann Glover. She was hanged as a witch in 1688, shortly before the much more famous witchcraft trials in nearby Salem.

Monsignor Ellis noted that a common hatred of the Catholic Church could unite Anglican clerics and Puritan ministers despite their differences and conflicts. One of the Intolerable Acts passed by the British Parliament that helped fuel the American Revolution was the Quebec Act of 1774, which granted freedom of worship to Roman Catholics in Canada.

New nation

The Patriot reliance on Catholic France for military, financial and diplomatic aid led to a sharp drop in anti-Catholic rhetoric. Indeed, the king replaced the pope as the demon patriots had to fight against. Anti-Catholicism remained strong among Loyalists, some of whom went to Canada after the war while most remained in the new nation. By the 1780s, Catholics were extended legal toleration in all of the New England states that previously had been so hostile. "In the midst of war and crisis, New Englanders gave up not only their allegiance to Britain but one of their most dearly held prejudices."

George Washington was a vigorous promoter of tolerance for all religious denominations as commander of the army (1775-1783) where he suppressed anti-Catholic celebrations in the Army and appealed to French Catholics in Canada to join the American Revolution; a few hundred of them did. Likewise he guaranteed a high degree of freedom of religion as president (1789-1797), when he often attended services of different denominations. The military alliance with Catholic France in 1778 changed attitudes radically in Boston. Local leaders enthusiastically welcomed French naval and military officers, realizing the alliance was critical to winning independence. The Catholic chaplain of the French army reported in 1781 that he was continually receiving "new civilities" from the best families in Boston; he also noted that "the people in general retain their own prejudices." By 1790, about 500 Catholics in Boston formed the first Catholic Church there.

Fear of the pope agitated some of America's Founding Fathers. For example, in 1788, John Jay urged the New York Legislature to prohibit Catholics from holding office. The legislature refused, but did pass a law designed to reach the same goal by requiring all office-holders to renounce foreign authorities "in all matters ecclesiastical as well as civil". Thomas Jefferson, looking at the Catholic Church in France, wrote, "History, I believe, furnishes no example of a priest-ridden people maintaining a free civil government", and "In every country and in every age, the priest has been hostile to liberty. He is always in alliance with the despot, abetting his abuses in return for protection to his own."

1840s–1850s

Anti-Catholic fears reached a peak in the nineteenth century when the Protestant population became alarmed by the influx of Catholic immigrants. Some claimed that the Catholic Church was the Whore of Babylon described in the Book of Revelation. The resulting "nativist" movement, which achieved prominence in the 1840s, was whipped into a frenzy of anti-Catholicism that led to mob violence, most notably the Philadelphia Nativist Riot of 1844. Historian David Montgomery argues that the Irish Catholic Democrats in Philadelphia had successfully appealed to the upper-class Whig leadership. The Whigs wanted to split the Democratic coalition, so they approved Bishop Kendrick's request that Catholic children be allowed to use their own Bible. That approval outraged the evangelical Protestant leadership, which rallied its support in Philadelphia and nationwide. Montgomery states:

- The school controversy, however, had united 94 leading clergymen of the city in a common pledge to strengthen Protestant education and "awaken the attention of the community to the dangers which... threaten these United States from the assaults of Romanism." The American Tract Society took up the battle cry and launched a national crusade to save the nation from the "spiritual despotism" of Rome. The whole Protestant edifice of churches, Bible societies, temperance societies, and missionary agencies was thus interposed against Catholic electoral maneuvers ...at the very moment when those maneuvers were enjoying some success.

The nativist movement found expression in a national political movement called the "American" or Know-Nothing Party of 1854–56. It had considerable success in local and state elections in 1854-55 by emphasizing nativism and warning against Catholics and immigrants. It nominated former president Millard Fillmore as its presidential candidate in the 1856 election. However, Fillmore was not anti-Catholic or nativist; his campaign concentrated almost entirely on national unity. Historian Tyler Anbinder says, "The American party had dropped nativism from its agenda." Fillmore won 22% of the national popular vote.

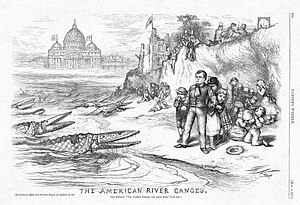

In the Orange Riots in New York City in 1871 and 1872, Irish Catholics violently attacked Irish Protestants, who carried orange banners.

Anti-Catholicism among American Jews further intensified in the 1850s during the international controversy over the Edgardo Mortara case, when a baptized Jewish boy in the Papal States was removed from his family and refused to return to them.

After 1875 many states passed constitutional provisions, called "Blaine Amendments", forbidding tax money be used to fund parochial