Measles

Measles is a highly contagious infectious disease caused by measles virus. Symptoms usually develop 10–12 days after exposure to an infected person and last 7–10 days. Initial symptoms typically include fever, often greater than 40 °C (104 °F), cough, runny nose, and inflamed eyes. Small white spots known as Koplik's spots may form inside the mouth two or three days after the start of symptoms. A red, flat rash which usually starts on the face and then spreads to the rest of the body typically begins three to five days after the start of symptoms. Common complications include diarrhea (in 8% of cases), middle ear infection (7%), and pneumonia (6%). These occur in part due to measles-induced immunosuppression. Less commonly seizures, blindness, or inflammation of the brain may occur. Other names include morbilli, rubeola, red measles, and English measles. Both rubella, also known as German measles, and roseola are different diseases caused by unrelated viruses.

Measles is an airborne disease which spreads easily from one person to the next through the coughs and sneezes of infected people. It may also be spread through direct contact with mouth or nasal secretions. It is extremely contagious–nine out of ten people who are not immune and share living space with an infected person will be infected. Furthermore, measles's reproductive number estimates vary beyond the frequently cited range of 12 to 18. People are infectious to others from four days before to four days after the start of the rash. While often regarded as a childhood illness, it can affect people of any age. Most people do not get the disease more than once. Testing for the measles virus in suspected cases is important for public health efforts. Measles is not known to occur in other animals.

Once a person has become infected, no specific treatment is available, although supportive care may improve outcomes. Such care may include oral rehydration solution (slightly sweet and salty fluids), healthy food, and medications to control the fever. Antibiotics should be prescribed if secondary bacterial infections such as ear infections or pneumonia occur. Vitamin A supplementation is also recommended for children. Among cases reported in USA between 1985 and 1992 the death was the outcome in just 0.2% of cases, but may be up to 10% in people with malnutrition. Most of those who die from the infection are less than five years old.

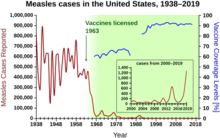

The measles vaccine is effective at preventing the disease, is exceptionally safe, and is often delivered in combination with other vaccines. Vaccination resulted in an 80% decrease in deaths from measles between 2000 and 2017, with about 85% of children worldwide having received their first dose as of 2017. Measles affects about 20 million people a year, primarily in the developing areas of Africa and Asia. It is one of the leading vaccine-preventable disease causes of death. In 1980, 2.6 million people died of it, and in 1990, 545,000 died; by 2014, global vaccination programs had reduced the number of deaths from measles to 73,000. Despite these trends, rates of disease and deaths increased from 2017 to 2019 due to a decrease in immunization.

Play media

Play mediaSigns and symptoms

Symptoms typically begin 10–14 days after exposure. The classic symptoms include a four-day fever (the 4 D's) and the three C's—cough, coryza (head cold, fever, sneezing), and conjunctivitis (red eyes)—along with a maculopapular rash. Fever is common and typically lasts for about one week; the fever seen with measles is often as high as 40 °C (104 °F).

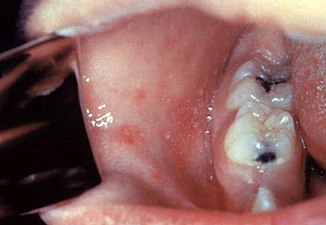

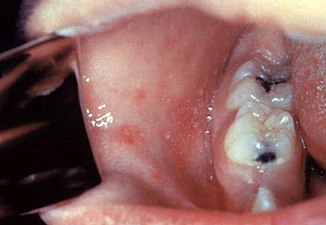

Koplik's spots seen inside the mouth are diagnostic for measles, but are temporary and therefore rarely seen. Koplik spots are small white spots that are commonly seen on the inside of the cheeks opposite the molars. They appear as "grains of salt on a reddish background." Recognizing these spots before a person reaches their maximum infectiousness can help reduce the spread of the disease.

The characteristic measles rash is classically described as a generalized red maculopapular rash that begins several days after the fever starts. It starts on the back of the ears and, after a few hours, spreads to the head and neck before spreading to cover most of the body, often causing itching. The measles rash appears two to four days after the initial symptoms and lasts for up to eight days. The rash is said to "stain", changing color from red to dark brown, before disappearing. Overall, measles usually resolves after about three weeks.

People who have been vaccinated against measles but have incomplete protective immunity may experience a form of modified measles. Modified measles is characterized by a prolonged incubation period, milder, and less characteristic symptoms (sparse and discrete rash of short duration).

A Filipino baby with measles

Koplik's spots on the third pre-eruptive day

Koplik's spots on the day of measles rash.

Complications

Complications of measles are relatively common, ranging from mild ones such as diarrhea to serious ones such as pneumonia (either direct viral pneumonia or secondary bacterial pneumonia), laryngotracheobronchitis (croup) (either direct viral laryngotracheobronchitis or secondary bacterial bronchitis), otitis media, acute brain inflammation (and very rarely subacute sclerosing panencephalitis), and corneal ulceration (leading to corneal scarring).

In addition, measles can suppress the immune system for weeks to months, and this can contribute to bacterial superinfections such as otitis media and bacterial pneumonia. Two months after recovery there is a 11–73% decrease in the number of antibodies against other bacteria and viruses.

The death rate in the 1920s was around 30% for measles pneumonia. People who are at high risk for complications are infants and children aged less than 5 years; adults aged over 20 years; pregnant women; people with compromised immune systems, such as from leukemia, HIV infection or innate immunodeficiency; and those who are malnourished or have vitamin A deficiency. Complications are usually more severe in adults. Between 1987 and 2000, the case fatality rate across the United States was three deaths per 1,000 cases attributable to measles, or 0.3%. In underdeveloped nations with high rates of malnutrition and poor healthcare, fatality rates have been as high as 28%. In immunocompromised persons (e.g., people with AIDS) the fatality rate is approximately 30%.

Even in previously healthy children, measles can cause serious illness requiring hospitalization. One out of every 1,000 measles cases progresses to acute encephalitis, which often results in permanent brain damage. One to three out of every 1,000 children who become infected with measles will die from respiratory and neurological complications.

Cause

Measles is caused by the measles virus, a single-stranded, negative-sense, enveloped RNA virus of the genus Morbillivirus within the family Paramyxoviridae.

The virus is highly contagious and is spread by coughing and sneezing via close personal contact or direct contact with secretions. Measles is the most contagious transmissible virus known. It remains infective for up to two hours in that airspace or nearby surfaces. Measles is so contagious that if one person has it, 90% of nearby non-immune people will also become infected. Humans are the only natural hosts of the virus, and no other animal reservoirs are known to exist.

Risk factors for measles virus infection include immunodeficiency caused by HIV or AIDS, immunosuppression following receipt of an organ or a stem cell transplant, alkylating agents, or corticosteroid therapy, regardless of immunization status; travel to areas where measles commonly occurs or contact with travelers from such an area; and the loss of passive, inherited antibodies before the age of routine immunization.

Pathophysiology

Once the measles virus gets onto the mucosa, it infects the epithelial cells in the trachea or bronchi. Measles virus uses a protein on its surface called hemagglutinin (H protein), to bind to a target receptor on the host cell, which could be CD46, which is expressed on all nucleated human cells, CD150, aka signaling lymphocyte activation molecule or SLAM, which is found on immune cells like B or T cells, and antigen-presenting cells, or nectin-4, a cellular adhesion molecule. Once bound, the fusion, or F protein helps the virus fuse with the membrane and ultimately get inside the cell.

As the virus is a single-stranded negative-sense RNA virus, it includes the enzyme RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp) which is used to transcribe its genome into a positive-sense mRNA strand.

After that it is ready to be translated into viral proteins, wrapped in the cell's lipid envelope, and sent out of the cell as a newly made virus. Within days, the measles virus spreads through local tissue and is picked up by dendritic cells and alveolar macrophages, and carried from that local tissue in the lungs to the local lymph nodes. From there it continues to spread, eventually getting into the blood and spreading to more lung tissue, as well as other organs like the intestines and the brain. Functional impairment of the infected dendritic cells by the measles virus is thought to contribute to measles-induced immunosuppression.

Diagnosis

Typically, clinical diagnosis begins with the onset of fever and malaise about 10 days after exposure to the measles virus, followed by the emergence of cough, coryza, and conjunctivitis that worsen in severity over 4 days of appearing. Observation of Koplik's spots is also diagnostic. Other possible condition that can result in these symptoms include parvovirus, dengue fever, Kawasaki disease, and scarlet fever. Laboratory confirmation is however strongly recommended.

Laboratory testing

Laboratory diagnosis of measles can be done with confirmation of positive measles IgM antibodies or detection of measles virus RNA from throat, nasal or urine specimen by using the reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction assay. This method is particularly useful to confirm cases when the IgM antibodies results are inconclusive. For people unable to have their blood drawn, saliva can be collected for salivary measles-specific IgA testing. Salivary tests used to diagnose measles involve collecting a saliva sample and testing for the presence of measles antibodies. This method is not ideal, as saliva contains many other fluids and proteins which may make it difficult to collect samples and detect measles antibodies. Saliva also contains 800 times fewer antibodies than blood samples do, which makes salivary testing additionally difficult. Positive contact with other people known to have measles adds evidence to the diagnosis.

Prevention

Mothers who are immune to measles pass antibodies to their children while they are still in the womb, especially if the mother acquired immunity through infection rather than vaccination. Such antibodies will usually give newborn infants some immunity against measles, but these antibodies are gradually lost over the course of the first nine months of life. Infants under one year of age whose maternal anti-measles antibodies have disappeared become susceptible to infection with the measles virus.

In developed countries, it is recommended that children be immunized against measles at 12 months, generally as part of a three-part MMR vaccine (measles, mumps, and rubella). The vaccine is generally not given before this age because such infants respond inadequately to the vaccine due to an immature immune system. A second dose of the vaccine is usually given to children between the ages of four and five, to increase rates of immunity. Measles vaccines have been given to over a billion people. Vaccination rates have been high enough to make measles relatively uncommon. Adverse reactions to vaccination are rare, with fever and pain at the injection site being the most common. Life-threatening adverse reactions occur in less than one per million vaccinations (<0.0001%).

In developing countries where measles is common, the World Health Organization (WHO) recommends two doses of vaccine be given, at six and nine months of age. The vaccine should be given whether the child is HIV-infected or not. The vaccine is less effective in HIV-infected infants than in the general population, but early treatment with antiretroviral drugs can increase its effectiveness. Measles vaccination programs are often used to deliver other child health interventions as well, such as bed nets to protect against malaria, antiparasite medicine and vitamin A supplements, and so contribute to the reduction of child deaths from other causes.

The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) recommends that all adult international travelers who do not have positive evidence of previous measles immunity receive two doses of MMR vaccine before traveling, although birth before 1957 is presumptive evidence of immunity. Those born in the United States before 1957 are likely to have been naturally infected with measles virus and generally need not be considered susceptible.

There have been false claims of an association between the measles vaccine and autism; this incorrect concern has reduced the rate of vaccination and increased the number of cases of measles where immunization rates became too low to maintain herd immunity. Additionally, there have been false claims that measles infection protects against cancer.

Administration of the MMR vaccine may prevent measles after exposure to the virus (post-exposure prophylaxis). Post-exposure prophylaxis guidelines are specific to jurisdiction and population. Passive immunization against measles by an intramuscular injection of antibodies could be effective up to the seventh day after exposure. Compared to no treatment, the risk of measles infection is reduced by 83%, and the risk of death by measles is reduced by 76%. However, the effectiveness of passive immunization in comparison to active measles vaccine is not clear.

The MMR vaccine is 95% effective for preventing measles after one dose if the vaccine is given to a child who is 12 months or older; if a second dose of the MMR vaccine is given, it will provide immunity in 99% of children.

There is no evidence that the measles vaccine virus can be transmitted to other persons.

Treatment

There is no specific antiviral treatment if measles develops. Instead the medications are generally aimed at treating superinfections, maintaining good hydration with adequate fluids, and pain relief. Some groups, like young children and the severely malnourished, are also given vitamin A, which act as an immunomodulator that boosts the antibody responses to measles and decreases the risk of serious complications.

Medications

Treatment is supportive, with ibuprofen or paracetamol (acetaminophen) to reduce fever and pain and, if required, a fast-acting medication to dilate the airways for cough. As for aspirin, some research has suggested a correlation between children who take aspirin and the development of Reye syndrome.

The use of vitamin A during treatment is recommended to decrease the risk of blindness; however, it does not prevent or cure the disease. A systematic review of trials into its use found no reduction in overall mortality, but two doses (200 000 IU) of vitamin A was shown to reduce mortality for measles in children younger than two years of age. It is unclear if zinc supplementation in children with measles affects outcomes as it has not been sufficiently studied. There are no adequate studies on whether Chinese medicinal herbs are effective.

Prognosis

Most people survive measles, though in some cases, complications may occur. About 1 in 4 individuals will be hospitalized and 1–2 in 1000 will die. Complications are more likely in children under age 5 and adults over age 20. Pneumonia is the most common fatal complication of measles infection and accounts for 56-86% of measles-related deaths.

Possible consequences of measles virus infection include laryngotracheobronchitis, sensorineural hearing loss, and—in about 1 in 10,000 to 1 in 300,000 cases—panencephalitis, which is usually fatal. Acute measles encephalitis is another serious risk of measles virus infection. It typically occurs two days to one week after the measles rash breaks out and begins with very high fever, severe headache, convulsions and altered mentation. A person with measles encephalitis may become comatose, and death or brain injury may occur.

For people having had measles, it is rare to ever have a symptomatic reinfection.

The measles virus can kill cells that make antibodies, and thus weakens the immune system which can cause deaths from other diseases. Suppression of the immune system by measles lasts about two years and has been epidemiologically implicated in up to 90% of childhood deaths in third world countries, and historically may have caused rather more deaths in the United States, the UK and Denmark than were directly caused by measles.

Epidemiology

Measles is extremely infectious and its continued circulation in a community depends on the generation of susceptible hosts by birth of children. In communities that generate insufficient new hosts the disease will die out. This concept was first recognized in measles by Bartlett in 1957, who referred to the minimum number supporting measles as the critical community size (CCS). Analysis of outbreaks in island communities suggested that the CCS for measles is around 250,000. To achieve herd immunity, more than 95% of the community must be vaccinated due to the ease with which measles is transmitted from person to person.

In 2011, the WHO estimated that 158,000 deaths were caused by measles. This is down from 630,000 deaths in 1990. As of 2018, measles remains a leading cause of vaccine-preventable deaths in the world. In developed countries the mortality rate is lower, for example in England and Wales from 2007 to 2017 death occurred between two and three cases out of 10,000. In children one to three cases out of every 1,000 die in the United States (0.1–0.2%). In populations with high levels of malnutrition and a lack of adequate healthcare, mortality can be as high as 10%. In cases with complications, the rate may rise to 20–30%. In 2012, the number of deaths due to measles was 78% lower than in 2000 due to increased rates of immunization among UN member states.

| WHO-Region | 1980 | 1990 | 2000 | 2005 | 2014 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| African Region | 1,240,993 | 481,204 | 520,102 | 316,224 | 71,574 |

| Region of the Americas | 257,790 | 218,579 | 1,755 | 66 | 19,898 |

| Eastern Mediterranean Region | 341,624 | 59,058 | 38,592 | 15,069 | 28,031 |

| European Region | 851,849 | 234,827 | 37,421 | 37,332 | 16,899 |

| South-East Asia Region | 199,535 | 224,925 | 61,975 | 83,627 | 112,418 |

| Western Pacific Region | 1,319,640 | 155,490 | 176,493 | 128,016 | 213,366 |

| Worldwide | 4,211,431 | 1,374,083 | 836,338 | 580,287 | 462,186 |

Even in countries where vaccination has been introduced, rates may remain high. Measles is a leading cause of vaccine-preventable childhood mortality. Worldwide, the fatality rate has been significantly reduced by a vaccination campaign led by partners in the Measles Initiative: the American Red Cross, the United States CDC, the United Nations Foundation, UNICEF and the WHO. Globally, measles fell 60% from an estimated 873,000 deaths in 1999 to 345,000 in 2005. Estimates for 2008 indicate deaths fell further to 164,000 globally, with 77% of the remaining measles deaths in 2008 occurring within the Southeast Asian region. There were 142,300 measles related deaths globally in 2018, of which most cases were reported from African and eastern Mediterranean regions. These estimates were slightly higher than that of 2017, when 124,000 deaths were reported due to measles infection globally.

In 2000, the WHO established the Global Measles and Rubella Laboratory Network (GMRLN) to provide laboratory surveillance for measles, rubella, and congenital rubella syndrome. Data from 2016 to 2018 show that the most frequently detected measles virus genotypes are decreasing, suggesting that increasing global population immunity has decreased the number of chains of transmission.

Cases reported in the first three months of 2019, were 300% higher than in the first three months of 2018, with outbreaks in every region of the world, even in countries with high overall vaccination coverage where it spread among clusters of unvaccinated people. The numbers of reported cases as of mid-November is over 413,000 globally, with an additional 250,000 cases in DRC (as reported through their national system),similar to the increasing trends of infection reported in the earlier months of 2019, compared to 2018. In 2019, the total number of cases worldwide climbed to 869,770. The number of cases reported for 2020 is lower compare to 2019. It has been suggested that the COVID-19 pandemic has affected vaccination campaigns around the world, including in countries currently experiencing outbreaks, which could affect the number of cases in the future.

Europe

In England and Wales, though deaths from measles were uncommon they averaged about 500 per year in the 1940s. Deaths diminished with the improvement of medical care in the 1950s but the incidence of the disease didn't retreat until vaccination was introduced in the late 1960s. Wider coverage was achieved in the 1980s with the measles, mumps and rubella, MMR vaccine.

In 2013–14, there were almost 10,000 cases in 30 European countries. Most cases occurred in unvaccinated individuals and over 90% of cases occurred in Germany, Italy, Netherlands, Romania, and United Kingdom. Between October 2014 and March 2015, a measles outbreak in the German capital of Berlin resulted in at least 782 cases. In 2017, numbers continued to increase in Europe to 21,315 cases, with 35 deaths. In preliminary figures for 2018, reported cases in the region increased 3-fold to 82,596 in 47 countries, with 72 deaths; Ukraine had the most cases (53,218), with the highest incidence rates being in Ukraine (1209 cases per million), Serbia (579), Georgia (564) and Albania (500). The previous year (2017) saw an estimated measles vaccine coverage of 95% for the first dose and 90% for the second dose in the region, the latter figure being the highest-ever estimated second-dose coverage.

In 2019, the United Kingdom, Albania, the Czech Republic, and Greece lost their measles-free status due to ongoing and prolonged spread of the disease in these countries. In the first 6 months of 2019, 90,000 cases occurred in Europe.

Americas

As a result of widespread vaccination, the disease was declared eliminated from the Americas in 2016. However, there were cases again in 2017, 2018, 2019, and 2020 in this region.

United States

In the United States, measles affected approximately 3,000 people per million in the 1960s before the vaccine was available. With consistent widespread childhood vaccination, this figure fell to 13 cases per million by the 1980s, and to about 1 case per million by the year 2000.

In 1991, an outbreak of measles in Philadelphia was centered at the Faith Tabernacle Congregation, a faith healing church that actively discouraged parishioners from vaccinating their children. Over 1400 people were infected with measles and nine children died.

Before immunization in the United States, between three and four million cases occurred each year. The United States was declared free of circulating measles in 2000, with 911 cases from 2001 to 2011. In 2014 the CDC said endemic measles, rubella, and congenital rubella syndrome had not returned to the United States. Occasional measles outbreaks persist, however, because of cases imported from abroad, of which more than half are the result of unvaccinated U.S. residents who are infected abroad and infect others upon return to the United States. The CDC continues to recommend measles vaccination throughout the population to prevent outbreaks like these.

In 2014, an outbreak was initiated in Ohio when two unvaccinated Amish men harboring asymptomatic measles returned to the United States from missionary work in the Philippines. Their return to a community with low vaccination rates led to an outbreak that rose to include a total of 383 cases across nine counties. Of the 383 cases, 340 (89%) occurred in unvaccinated individuals.

From 4 January, to 2 April 2015, there were 159 cases of measles reported to the CDC. Of those 159 cases, 111 (70%) were determined to have come from an earlier exposure in late December 2014. This outbreak was believed to have originated from the Disneyland theme park in California. The Disneyland outbreak was held responsible for the infection of 147 people in seven U.S. states as well as Mexico and Canada, the majority of which were either unvaccinated or had unknown vaccination status. Of the cases 48% were unvaccinated and 38% were unsure of their vaccination status. The initial exposure to the virus was never identified.

In 2015, a U.S. woman in Washington state died of pneumonia, as a result of measles. She was the first fatality in the U.S. from measles since 2003. The woman had been vaccinated for measles and was taking immunosuppressive drug for another condition. The drugs suppressed the woman's immunity to measles, and the woman became infected with measles; she did not develop a rash, but contracted pneumonia, which caused her death.

In June 2017, the Maine Health and Environmental Testing Laboratory confirmed a case of measles in Franklin County. This instance marks the first case of measles in 20 years for the state of Maine. In 2018 one case occurred in Portland, Oregon, with 500 people exposed; 40 of them lacked immunity to the virus and were being monitored by county health officials as of 2 July 2018. There were 273 cases of measles reported throughout the United States in 2018, including an outbreak in Brooklyn with more than 200 reported cases from October 2018 to February 2019. The outbreak was tied with population density of the Orthodox Jewish community, with the initial exposure from an unvaccinated child that caught measles while visiting Israel.

A resurgence of measles occurred during 2019, which has been generally tied to parents choosing not to have their children vaccinated as most of the reported cases have occurred in people 19 years old or younger. Cases were first reported in Washington state in January, with an outbreak of at least 58 confirmed cases most within Clark County, which has a higher rate of vaccination exemptions compared to the rest of the state; nearly one in four kindergartners in Clark did not receive vaccinations, according to state data. This led Washington state governor Jay Inslee to declare a state of emergency, and the state's congress to introduce legislation to disallow vaccination exemption for personal or philosophical reasons. In April 2019, New York Mayor Bill de Blasio declared a public health emergency because of "a huge spike" in cases of measles where there were 285 cases centred on the Orthodox Jewish areas of Brooklyn in 2018, while there were only two cases in 2017. There were 168 more in neighboring Rockland County. Other outbreaks have included Santa Cruz County and Butte County in California, and the states of New Jersey and Michigan. As of April 2019[update], there have been 695 cases of measles reported in 22 states. This is the highest number of measles cases since it was declared eradicated in 2000. From 1 January, to 31 December 2019, 1,282 individual cases of measles were confirmed in 31 states. This is the greatest number of cases reported in the U.S. since 1992. Of the 1,282 cases, 128 of the people who got measles were hospitalized, and 61 reported having complications, including pneumonia and encephalitis.

Brazil

The spread of measles had been interrupted in Brazil in 2016, with the last known case twelve months earlier. This last case was in the state of Ceará.

Brazil won a measles elimination certificate by the Pan American Health Organization in 2016, but the Ministry of Health has proclaimed that the country has struggled to keep this certificate, since two outbreaks had already been identified in 2018, one in the state of Amazonas and another one in Roraima, in addition to cases in other states (Rio de Janeiro, Rio Grande do Sul, Pará, São Paulo and Rondônia), totaling 1053 confirmed cases until 1 August 2018. In these outbreaks, and in most other cases, the contagion was related to the importation of the virus, especially from Venezuela. This was confirmed by the genotype of the virus (D8) that was identified, which is the same that circulates in Venezuela.

Southeast Asia

In the Vietnamese measles epidemic in spring of 2014, an estimated 8,500 measles cases were reported as of 19 April, with 114 fatalities; as of 30 May, 21,639 suspected measles cases had been reported, with 142 measles-related fatalities. In the Naga Self-Administered Zone in a remote northern region of Myanmar, at least 40 children died during a measles outbreak in August 2016 that was probably caused by lack of vaccination in an area of poor health infrastructure. Following the 2019 Philippines measles outbreak, 23,563 measles cases have been reported in the country with 338 fatalities. A measles outbreak also happened among the Malaysian Orang Asli sub-group of Batek people in the state of Kelantan from May 2019, causing the deaths of 15 from the tribe.

South Pacific

A measles outbreak in New Zealand has 2193 confirmed cases and two deaths. A measles outbreak in Tonga has 612 cases of measles.

Samoa

A measles outbreak in Samoa in late 2019 has over 5,700 cases of measles and 83 deaths, out of a Samoan population of 200,000. Over three percent of the population were infected, and a state of emergency was declared from 17 November to 7 December. A vaccination campaign brought the measles vaccination rate from 31 to 34% in 2018 to an estimated 94% of the eligible population in December 2019.

Africa

The Democratic Republic of the Congo and Madagascar have reported