Epilepsy

Overview

Epilepsy — also known as a seizure disorder — is a brain disorder that causes recurring seizures. There are many types of epilepsy. In some people, the cause can be identified. In others, the cause isn't known.

Epilepsy is common. It's estimated that 1 in 26 people develops the disorder, according to the Epilepsy Foundation. Epilepsy affects people of all genders, races, ethnic backgrounds and ages.

Seizure symptoms can vary widely. Some people may lose awareness during a seizure but others don't. Some people stare blankly for a few seconds during a seizure. Others may repeatedly twitch their arms or legs, movements known as convulsions or spasms.

Having a single seizure doesn't mean you have epilepsy. Epilepsy is diagnosed if you've had at least two unprovoked seizures at least 24 hours apart. Unprovoked seizures don't have a clear cause.

Treatment with medicines or sometimes surgery can control seizures for most people with epilepsy. Some people require lifelong treatment. For others, seizures eventually go away. Some children with epilepsy may outgrow the condition with age.

Symptoms

Seizure symptoms vary depending on the type of seizure. Because epilepsy is caused by certain activity in the brain, seizures can affect any brain process. Seizure symptoms may include:

- Temporary confusion.

- A staring spell.

- Stiff muscles.

- Uncontrollable jerking movements of the arms and legs.

- Loss of consciousness or awareness.

- Psychological symptoms such as fear, anxiety or deja vu.

Sometimes, people with epilepsy may have changes in their behavior. They also may have symptoms of psychosis.

Most people with epilepsy tend to have the same type of seizure each time. Symptoms are usually similar from episode to episode.

Warning signs of seizures

Some people with focal seizures experience warning signs in the moments before a seizure begins. These warning signs are known as aura. They might include a feeling in the stomach. Or they might include an emotion such as fear. Some people might feel deja vu. Aura also might be a taste or a smell. It might even be visual, such as a steady or flashing light, a color, or a shape. Some people may experience dizziness and loss of balance. Others may see things that aren't there, known as hallucinations.

Seizures are classified as either focal or generalized, based on how and where the brain activity causing the seizure begins.

When seizures appear to result from activity in just one area of the brain, they're called focal seizures. These seizures fall into two categories:

- Focal seizures without loss of consciousness. Once called simple partial seizures, these seizures don't cause a loss of consciousness. They may alter emotions or change the way things look, smell, feel, taste or sound. Some people experience deja vu. This type of seizure also may result in involuntary jerking of one body part, such as an arm or a leg, and spontaneous sensory symptoms such as tingling, dizziness and flashing lights.

- Focal seizures with impaired awareness. Once called complex partial seizures, these seizures involve a change or loss of consciousness or awareness. This type of seizure may seem like being in a dream. During a focal seizure with impaired awareness, people may stare into space and not respond in typical ways to the environment. They also may perform repetitive movements, such as hand rubbing, chewing, swallowing or walking in circles.

Symptoms of focal seizures may be confused with other neurological disorders, such as migraine, narcolepsy or mental illness. A thorough examination and testing are needed to distinguish epilepsy from other disorders.

Types of focal seizures include:

- Frontal lobe seizures. Frontal lobe seizures begin in the front of the brain. This is the part of the brain that controls movement. Frontal lobe seizures cause people to move their heads and eyes to one side. They won't respond when spoken to and may scream or laugh. They might extend one arm and flex the other arm. They also might make repetitive movements such as rocking or bicycle pedaling.

- Temporal lobe seizures. Temporal lobe seizures begin in the areas of the brain called the temporal lobes. The temporal lobes process emotions and play a role in short-term memory. People who have these seizures often experience an aura. The aura may include sudden emotion such as fear or joy, a sudden taste or smell, a feeling of deja vu, or a rising sensation in the stomach. During the seizure, people may lose awareness of their surroundings, stare into space, smack their lips, swallow or chew repeatedly, or have unusual movements of their fingers.

- Occipital lobe seizures. These seizures begin in the area of the brain called the occipital lobe. This lobe affects vision and how people see. People who have this type of seizure may have hallucinations. Or they may lose some or all of their vision during the seizure. These seizures also might cause eye blinking or make the eyes move.

Generalized seizures

Seizures that appear to involve all areas of the brain are called generalized seizures. Generalized seizures include:

- Absence seizures. Absence seizures, previously known as petit mal seizures, typically occur in children. Symptoms include staring into space with or without subtle body movements. Movements may include eye blinking or lip smacking and only last 5 to 10 seconds. These seizures may occur in clusters, happening as often as 100 times a day, and cause a brief loss of awareness.

- Tonic seizures. Tonic seizures cause stiff muscles and may affect consciousness. These seizures usually affect muscles in the back, arms and legs and may cause falls to the ground.

- Atonic seizures. Atonic seizures, also known as drop seizures, cause a loss of muscle control. Since this most often affects the legs, it often causes sudden collapse or falls to the ground.

- Clonic seizures. Clonic seizures are associated with repeated or rhythmic jerking muscle movements. These seizures usually affect the neck, face and arms.

- Myoclonic seizures. Myoclonic seizures usually appear as sudden brief jerks or twitches and usually affect the upper body, arms and legs.

- Tonic-clonic seizures. Tonic-clonic seizures, previously known as grand mal seizures, are the most dramatic type of epileptic seizure. They can cause an abrupt loss of consciousness and body stiffening, twitching and shaking. They sometimes cause loss of bladder control or biting of the tongue.

When to see a doctor

Seek immediate medical help if any of the following occurs:

- The seizure lasts more than five minutes.

- Breathing or consciousness doesn't return after the seizure stops.

- A second seizure follows immediately.

- You have a high fever.

- You're pregnant.

- You have diabetes.

- You've injured yourself during the seizure.

- You continue to have seizures even though you've been taking anti-seizure medicine.

If you experience a seizure for the first time, seek medical advice.

Causes

Epilepsy has no identifiable cause in about half the people with the condition. In the other half, the condition may be traced to various factors, including:

-

Genetic influence. Some types of epilepsy run in families. In these instances, it's likely that there's a genetic influence. Researchers have linked some types of epilepsy to specific genes. But some people have genetic epilepsy that isn't hereditary. Genetic changes can occur in a child without being passed down from a parent.

For most people, genes are only part of the cause of epilepsy. Certain genes may make a person more sensitive to environmental conditions that trigger seizures.

- Head trauma. Head trauma as a result of a car accident or other traumatic injury can cause epilepsy.

- Factors in the brain. Brain tumors can cause epilepsy. Epilepsy also may be caused by the way blood vessels form in the brain. People with blood vessel conditions such as arteriovenous malformations and cavernous malformations can have seizures. And in adults older than age 35, stroke is a leading cause of epilepsy.

- Infections. Meningitis, HIV, viral encephalitis and some parasitic infections can cause epilepsy.

- Injury before birth. Before they're born, babies are sensitive to brain damage that could be caused by several factors. They might include an infection in the mother, poor nutrition or oxygen deficiencies. This brain damage can result in epilepsy or cerebral palsy.

- Developmental disorders. Epilepsy can sometimes happen with developmental disorders. People with autism are more likely to have epilepsy than are people without autism. Research also has found that people with epilepsy are more likely to have other developmental disorders such as attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Having both conditions may be related to the genes involved in both epilepsy and developmental disorders.

Risk factors

Certain factors may increase your risk of epilepsy:

- Age. The onset of epilepsy is most common in children and older adults, but the condition can occur at any age.

- Family history. If you have a family history of epilepsy, you may be at an increased risk of developing a seizure disorder.

- Head injuries. Head injuries are responsible for some cases of epilepsy. You can reduce your risk by wearing a seat belt while riding in a car and by wearing a helmet while bicycling, skiing, riding a motorcycle or engaging in other activities with a high risk of head injury.

- Stroke and other vascular diseases. Stroke and other blood vessel diseases can cause brain damage. Brain damage may trigger seizures and epilepsy. You can take a number of steps to reduce your risk of these diseases, including limiting your intake of alcohol and avoiding cigarettes, eating a healthy diet, and exercising regularly.

- Dementia. Dementia can increase the risk of epilepsy in older adults.

- Brain infections. Infections such as meningitis, which causes inflammation in the brain or spinal cord, can increase your risk.

- Seizures in childhood. High fevers in childhood can sometimes be associated with seizures. Children who have seizures due to high fevers generally won't develop epilepsy. The risk of epilepsy increases if a child has a long fever-associated seizure, another nervous system condition or a family history of epilepsy.

Complications

Having a seizure at certain times can lead to circumstances that are dangerous to yourself or others.

- Falling. If you fall during a seizure, you can injure your head or break a bone.

- Drowning. If you have epilepsy, you're 13 to 19 times more likely to drown while swimming or bathing than the rest of the population because of the possibility of having a seizure while in the water.

-

Car accidents. A seizure that causes either loss of awareness or control can be dangerous if you're driving a car or operating other equipment.

Many states have driver's license restrictions related to a driver's ability to control seizures. In these states, there is a minimum amount of time that a driver must be seizure-free, ranging from months to years, before being allowed to drive.

- Problems with sleep. People who have epilepsy also tend to have sleep problems, such as trouble falling asleep or staying asleep, known as insomnia.

-

Pregnancy complications. Seizures during pregnancy pose dangers to both mother and baby, and certain anti-epileptic medicines increase the risk of birth defects. If you have epilepsy and you're considering becoming pregnant, get medical help as you plan your pregnancy.

Most women with epilepsy can become pregnant and have healthy babies. You'll need to be carefully monitored throughout pregnancy, and medicines may need to be adjusted. It's very important that you work with your health care team to plan your pregnancy.

- Memory problems. People with some types of epilepsy have memory problems.

Emotional health issues

People with epilepsy are more likely to have psychological problems. Problems may be a result of dealing with the condition itself as well as medicine side effects. But even people with well-controlled epilepsy are at increased risk. Emotional health problems that may affect people with epilepsy include:

- Depression.

- Anxiety

- Suicidal thoughts and behaviors.

Other life-threatening complications of epilepsy are uncommon but may happen These include:

- Status epilepticus. This condition occurs if you're in a state of continuous seizure activity lasting more than five minutes or if you have frequent recurrent seizures without regaining full consciousness in between them. People with status epilepticus have an increased risk of permanent brain damage and death.

-

Sudden unexpected death in epilepsy (SUDEP). People with epilepsy also have a small risk of sudden unexpected death. The cause is unknown, but some research shows it may occur due to heart or respiratory conditions.

People with frequent tonic-clonic seizures or people whose seizures aren't controlled by medicines may be at higher risk of SUDEP. Overall, about 1% of people with epilepsy die of SUDEP. It's most common in those with severe epilepsy that doesn't respond to treatment.

Diagnosis

To diagnose your condition, your health care provider will likely review your symptoms and medical history. You may have several tests to diagnose epilepsy and to detect the cause of seizures. Your evaluation may include:

- A neurological exam. This exam tests your behavior, motor abilities, mental function and other areas to diagnose your condition and determine the type of epilepsy you may have.

- Blood tests. A blood sample can detect signs of infections, genetic conditions or other conditions that may be associated with seizures.

-

Genetic testing. In some people with epilepsy, genetic testing may give more information about the condition and how to treat it. Genetic testing is most often performed in children but also may be helpful in some adults with epilepsy.

You also may have one or more brain imaging tests and scans that detect brain changes:

-

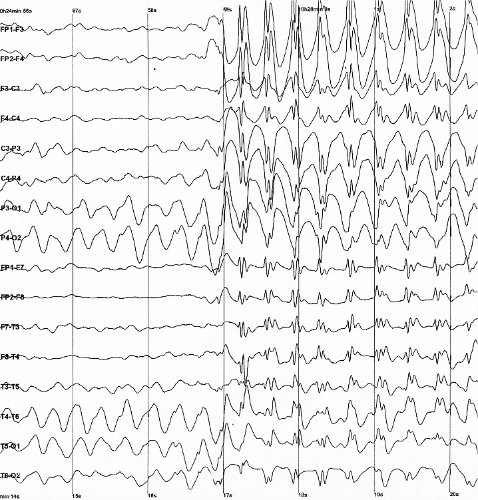

Electroencephalogram (EEG). This is the most common test used to diagnose epilepsy. In this test, electrodes are attached to your scalp with a paste-like substance or cap. The electrodes record the electrical activity of your brain.

If you have epilepsy, it's common to have changes in your typical pattern of brain waves. These changes occur even when you're not having a seizure. Your health care provider may monitor you on video during an EEG to detect and record any seizures you experience. This may be done while you're awake or asleep. Recording the seizures may help determine what kind of seizures you're having or rule out other conditions.

The test may be done in a health care provider's office or the hospital. If appropriate, you also may have an ambulatory EEG, which you wear at home while the EEG records seizure activity over the course of a few days.

You may get instructions to do something that can cause seizures, such as getting little sleep prior to the test.

- High-density EEG. In a variation of an EEG test, you may have a high-density EEG, which spaces electrodes more closely than does conventional EEG. High-density EEG may help more precisely determine which areas of your brain are affected by seizures.

- Computerized tomography (CT) scan. A CT scan uses X-rays to obtain cross-sectional images of your brain. CT scans can detect tumors, bleeding or cysts in the brain that might be causing epilepsy.

- Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). An MRI uses powerful magnets and radio waves to create a detailed view of the brain. Like a CT scan, an MRI looks at the structure of the brain to detect what may be causing seizures. But an MRI provides a more detailed look at the brain than a CT scan.

- Functional MRI (fMRI). A functional MRI measures the changes in blood flow that occur when specific parts of the brain are working. This test may be used before surgery to identify the exact locations of critical functions, such as speech and movement, so that surgeons can avoid injuring those places while operating.

- Positron emission tomography (PET). PET scans use a small amount of low-dose radioactive material that's injected into a vein to help visualize metabolic activity of the brain and detect changes. Areas of the brain with low metabolism may indicate places where seizures occur.

Single-photon emission computerized tomography (SPECT). This type of test is used primarily if MRI and EEG didn't pinpoint the location in the brain where the seizures are originating.

A SPECT test uses a small amount of low-dose radioactive material that's injected into a vein to create a detailed, 3D map of the blood flow activity in the brain during seizures. Areas of higher than typical blood flow during a seizure may indicate places where seizures occur.

Another type of SPECT test called subtraction ictal SPECT coregistered to MRI (SISCOM) may provide even more-detailed results by overlapping the SPECT results with brain MRI results.

- Neuropsychological tests. These tests assess thinking, memory and speech skills. The test results help determine which areas of the brain are affected by seizures.

Along with your test results, a combination of analysis techniques may be used to help pinpoint where in the brain seizures start:

- Statistical parametric mapping (SPM). SPM is a method of comparing areas of the brain that have increased blood flow during seizures to the same areas of the brains of people who don't have seizures. This provides information about where seizures begin.

- Electrical source imaging (ESI). ESI is a technique that takes EEG data and projects it onto an MRI of the brain to show areas where seizures are occurring. This technique provides more-precise detail than does EEG alone.

- Magnetoencephalography (MEG). MEG measures the magnetic fields produced by brain activity. This helps identify potential areas where seizures start. MEG can be more accurate than EEG because the skull and tissue surrounding the brain interfere less with magnetic fields than with electrical impulses. MEG and MRI together provide images that show areas of the brain both affected by seizures and not affected by seizures.

Accurate diagnosis of your seizure type and where seizures begin gives you the best chance for finding an effective treatment.

Treatment

Treatment can help people diagnosed with epilepsy have fewer seizures or even completely stop having seizures. Possible treatments include:

- Medicines.

- Surgery.

- Therapies that stimulate the brain using a device.

- A ketogenic diet.

Medication

Most people with epilepsy can become seizure-free by taking one anti-seizure medicine, which is also called anti-epileptic medicine. Others may be able to decrease the frequency and intensity of their seizures by taking a combination of medicines.

Many children with epilepsy who aren't experiencing epilepsy symptoms can eventually discontinue medicines and live a seizure-free life. Many adults can discontinue medicines after two or more years without seizures. Your health care team can advise you about the appropriate time to stop taking medicines.

Finding the right medicine and dosage can be complex. Your provider may consider your condition, frequency of seizures, age and other factors when choosing which medicine to prescribe. Your provider also may review any other medicines you may be taking to ensure the anti-epileptic medicines won't interact with them.

You may first take a single medicine at a relatively low dosage and then increase the dosage gradually until your seizures are well controlled.

There are more than 20 different types of anti-seizure medicines available. The medicines that you take to treat your epilepsy depend on the type of seizures you have, as well as other factors such as your age and other health conditions.

These medicines may have some side effects. Mild side effects include:

- Fatigue.

- Dizziness.

- Weight gain.

- Loss of bone density.

- Skin rashes.

- Loss of coordination.

- Speech problems.

- Memory and thinking problems.

More-severe but rare side effects include:

- Depression.

- Suicidal thoughts and behaviors.

- Severe rash.

- Inflammation of certain organs, such as the liver.

To achieve the best seizure control possible with medicine, follow these steps:

- Take medicines exactly as prescribed.

- Always call your health care provider before switching to a generic version of your medicine or taking other medicines — those you get with or without a prescription — or herbal remedies.

- Never stop taking your medicine without talking to your health care provider.

- Notify your health care provider immediately if you notice new or increased feelings of depression, suicidal thoughts, or unusual changes in your mood or behaviors.

- Tell your health care provider if you have migraines. Your provider may prescribe one of the anti-epileptic medicines that can prevent your migraines and treat epilepsy.

At least half the people newly diagnosed with epilepsy become seizure-free with their first medicine. If anti-seizure medicines don't provide good results, you may be able to have surgery or other therapies. You'll likely have regular follow-up appointments with your health care provider to evaluate your condition and medicines.

Surgery

When medicines do not provide adequate control of seizures, epilepsy surgery may be an option. With epilepsy surgery, a surgeon removes the area of your brain that's causing seizures.

Surgery usually happens when tests show that:

- Your seizures originate in a small, well-defined area of your brain.

- The area in your brain to be operated on doesn't interfere with vital functions such as speech, language, motor function, vision or hearing.

For some types of epilepsy, minimally invasive approaches such as MRI-guided stereotactic laser ablation may provide effective treatment when an open procedure may be too risky. In these procedures, a thermal laser probe is directed at the specific area in the brain causing seizures to destroy that tissue in an effort to better control the seizures.

Although you may continue to need some medicine to help prevent seizures after successful surgery, you may be able to take fewer medicines and reduce your doses.

In a small number of people, surgery for epilepsy can cause complications such as permanently altering thinking abilities. Talk to your surgical team members about their experience, success rates and complication rates with the procedure you're considering.

Therapies

Apart from medicines and surgery, these potential therapies offer an alternative for treating epilepsy:

-

Vagus nerve stimulation. Vagus nerve stimulation may be an option when medicines haven't worked well enough to control seizures and surgery isn't possible. In vagus nerve stimulation, a device called a vagus nerve stimulator is implanted underneath the skin of the chest, similar to a heart pacemaker. Wires from the stimulator are connected to the vagus nerve in the neck.

The battery-powered device sends bursts of electrical energy through the vagus nerve and to the brain. It's not clear how this inhibits seizures, but the device can usually reduce seizures by 20% to 40%.

Most people still need to take anti-epileptic medicine, although some people may be able to lower their medicine dose. Vagus nerve stimulation side effects may include throat pain, hoarse voice, shortness of breath or coughing.

- Deep brain stimulation. In deep brain stimulation, surgeons implant electrodes into a specific part of the brain, typically the thalamus. The electrodes are connected to a generator implanted in the chest. The generator regularly sends electrical pulses to the brain at timed intervals and may reduce seizures. Deep brain stimulation is often used for people whose seizures don't get better with medicine.

- Responsive neurostimulation. These implantable, pacemaker-like devices can help significantly reduce how often seizures occur. These responsive stimulation devices analyze brain activity patterns to detect seizures as they start and deliver an electrical charge or medicine to stop the seizure before it causes impairment. Research shows that this therapy has few side effects and can provide long-term seizure relief.

Ketogenic diet

Some children and adults with epilepsy have been able to reduce their seizures by following a strict diet that's high in fats and low in carbohydrates. This may be an option when medicines aren't helping to control epilepsy.

In this diet, called a ketogenic diet, the body breaks down fats instead of carbohydrates for energy. After a few years, some children may be able to stop the ketogenic diet — under close supervision of their health care providers — and remain seizure-free.

Experts don't fully know how a ketogenic diet works to reduce seizures. But researchers think that the diet creates chemical changes that suppress seizures. The diet also alters the actions of brain cells to reduce seizures.

Get medical advice if you or your child is considering a ketogenic diet. It's important to make sure that your child doesn't become malnourished when following the diet.

Side effects of a ketogenic diet may include dehydration, constipation, slowed growth because of nutritional deficiencies and a buildup of uric acid in the blood, which can cause kidney stones. These side effects are uncommon if the diet is properly and medically supervised.

Following a ketogenic diet can be a challenge. Low-glycemic index and modified Atkins diets offer less restrictive alternatives that may still provide some benefit for seizure control.

Potential future treatments

Researchers are studying many potential new treatments for epilepsy, including:

- Continuous stimulation of the seizure onset zone, known as subthreshold stimulation. Subthreshold stimulation — continuous stimulation to an area of the brain below a level that's physically noticeable — appears to improve seizure outcomes and quality of life for some people with seizures. Subthreshold stimulation helps stop a seizure before it happens. This treatment approach may work in people who have seizures that start in an area of the brain called the eloquent area that can't be removed because it would affect speech and motor functions. Or it might benefit people whose seizure characteristics mean their chances of successful treatment with responsive neurostimulation are low.

- Minimally invasive surgery. New minimally invasive surgical techniques, such as MRI-guided focused ultrasound, show promise for treating seizures. These surgeries have fewer risks than traditional open-brain surgery for epilepsy.

- Transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS). TMS applies focused magnetic fields on areas of the brain where seizures occur to treat seizures without the need for surgery. It may be used for patients whose seizures occur close to the surface of the brain and can't be treated with surgery.

- External trigeminal nerve stimulation. Similar to vagus nerve stimulation, a device stimulates specific nerves to reduce frequency of seizures. But unlike in vagus nerve stimulation, the device is worn outside the body so that no surgery is needed to put the device in the body. In studies, external trigeminal nerve stimulation provided improvements in both seizure control and mood.

Clinical trials

Explore Mayo Clinic studies testing new treatments, interventions and tests as a means to prevent, detect, treat or manage this condition.

Lifestyle and home remedies

Understanding your condition can help you take better control of it:

- Take your medicine correctly. Don't adjust your dosage before talking to a member of your health care team. If you feel that your medicine should be changed, discuss it with your provider.

- Get enough sleep. Lack of sleep can trigger seizures. Be sure to get adequate rest every night.

- Wear a medical alert bracelet. This will help emergency personnel know how to treat you correctly.

- Exercise. Exercising may help keep you physically healthy and reduce depression. Make sure to drink enough water, and rest if you get tired during exercise.

In addition, make healthy life choices, such as managing stress, limiting alcoholic beverages and avoiding cigarettes.

Coping and support

Uncontrolled seizures and their effects on your life may at times feel overwhelming or lead to depression. It's important not to let epilepsy hold you back. You can still live an active, full life. To help cope:

- Educate yourself and your friends and family about epilepsy so that they understand the condition.

- Try to ignore negative reactions from people. It helps to learn about epilepsy so that you know the facts as opposed to misconceptions about the disease. And try to keep your sense of humor.

- Live as independently as possible. Continue to work, if possible. If you can't drive because of your seizures, investigate public transportation options near you. If you aren't allowed to drive, you might consider moving to a city with good public transportation options.

- Find a health care provider you like and with whom you feel comfortable.

- Try not to constantly worry about having a seizure.

- Find an epilepsy support group to meet people who understand what you're going through.

If your seizures are so severe that you can't work outside your home, there are still ways to feel productive and connected to people. You may consider working from home.

Let people you work and live with know the correct way to handle a seizure in case they are with you when you have one. You may offer them suggestions, such as:

- Carefully roll the person onto one side to prevent choking.

- Place something soft under the person's head.

- Loosen tight neckwear.

- Don't try to put your fingers or anything else in the person's mouth. People with epilepsy will not "swallow" their tongues during a seizure — it's physically impossible.

- Don't try to restrain someone having a seizure.

- If the person is moving, clear away dangerous objects.

- If immediate medical help is needed, stay with the person until medical personnel arrive.

- Observe the person closely so that you can provide details on what happened.

- Time the seizures.

- Be calm during the seizures.

Preparing for your appointment

You're likely to start by seeing your primary care provider. However, when you call to set up an appointment, you may be referred immediately to a specialist. This specialist may be a doctor trained in brain and nervous system conditions, known as a neurologist, or a neurologist trained in epilepsy, known as an epileptologist.

Because appointments can be brief, and because there's often a lot to talk about, it's a good idea to be well prepared for your appointment. Here's some information to help you get ready for your appointment, and what to expect.

What you can do

-

Keep a detailed seizure calendar. Each time a seizure occurs, write down the time, the type of seizure you experienced and how long it lasted. Also make note of any circumstances, such as missed medicines, sleep deprivation, increased stress, menstruation or other events that might trigger seizure activity.

Seek input from people who may observe your seizures, including family, friends and co-workers, so that you can record information you may not know.

- Be aware of any pre-appointment restrictions. At the time you make the appointment, ask if there's anything you need to do in advance, such as restrict your diet.

- Write down key personal information, including any major stresses or recent life changes.

- Make a list of all medicines, vitamins or supplements that you're taking.

-

Take a family member or friend along. Sometimes it can be difficult to remember all the information provided to you during an appointment. Someone who accompanies you may remember something that you missed or forgot.

Also, because you may not be aware of everything that happens when you're having a seizure, someone else who has seen your seizures may be able to answer questions during your appointment.

- Write down questions to ask your health care provider. Preparing a list of questions will help you make the most of your appointment time.

For epilepsy, some basic questions include:

- What is likely causing my seizures?

- What kinds of tests do I need?

- Is my epilepsy likely temporary or chronic?

- What treatment approach do you recommend?

- What are the alternatives to the primary approach that you're suggesting?

- How can I make sure that I don't hurt myself if I have another seizure?

- I have these other health conditions. How can I best manage them together?

- Are there any restrictions that I need to follow?

- Should I see a specialist? What will that cost, and will my insurance cover it?

- Is there a generic alternative to the medicine you're prescribing?

- Are there any brochures or other printed material that I can take home with me? What websites do you recommend?

In addition to the questions that you've prepared, don't hesitate to ask questions during your appointment at any time that you don't understand something.

What to expect from your doctor

Your health care provider is likely to ask you a number of questions, such as:

- When did you first begin experiencing seizures?

- Do your seizures seem to be triggered by certain events or conditions?

- Do you have similar sensations just before the onset of a seizure?

- Have your seizures been frequent or occasional?

- What symptoms do you have when you experience a seizure?

- What, if anything, seems to improve your seizures?

- What, if anything, appears to worsen your seizures?

What you can do in the meantime

Certain conditions and activities can trigger seizures, so it may be helpful to:

- Avoid drinking excessive amounts of alcohol.

- Avoid using nicotine.

- Get enough sleep.

- Reduce stress.

Also, it's important to start keeping a log of your seizures before your appointment.