Epilepsy

Epilepsy is a group of neurological disorders characterized by recurrent epileptic seizures. Epileptic seizures are episodes that can vary from brief and nearly undetectable periods to long periods of vigorous shaking. These episodes can result in physical injuries, including occasionally broken bones. In epilepsy, seizures have a tendency to recur and, as a rule, have no immediate underlying cause. Isolated seizures that are provoked by a specific cause such as poisoning are not deemed to represent epilepsy. People with epilepsy may be treated differently in various areas of the world and experience varying degrees of social stigma due to their condition.

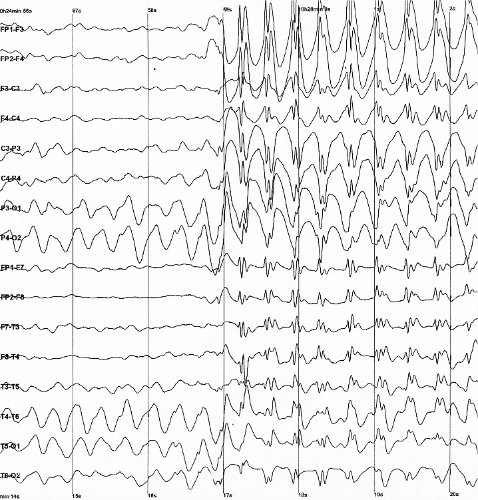

The underlying mechanism of epileptic seizures is excessive and abnormal neuronal activity in the cortex of the brain. The reason this occurs in most cases of epilepsy is unknown. Some cases occur as the result of brain injury, stroke, brain tumors, infections of the brain, or birth defects through a process known as epileptogenesis. Known genetic mutations are directly linked to a small proportion of cases. The diagnosis involves ruling out other conditions that might cause similar symptoms, such as fainting, and determining if another cause of seizures is present, such as alcohol withdrawal or electrolyte problems. This may be partly done by imaging the brain and performing blood tests. Epilepsy can often be confirmed with an electroencephalogram (EEG), but a normal test does not rule out the condition.

Epilepsy that occurs as a result of other issues may be preventable. Seizures are controllable with medication in about 70% of cases; inexpensive anti-seizure medications are often available. In those whose seizures do not respond to medication, surgery, neurostimulation or dietary changes may then be considered. Not all cases of epilepsy are lifelong, and many people improve to the point that treatment is no longer needed.

As of 2015[update], about 39 million people have epilepsy. Nearly 80% of cases occur in the developing world. In 2015, it resulted in 125,000 deaths, an increase from 112,000 in 1990. Epilepsy is more common in older people. In the developed world, onset of new cases occurs most frequently in babies and the elderly. In the developing world, onset is more common in older children and young adults due to differences in the frequency of the underlying causes. About 5–10% of people will have an unprovoked seizure by the age of 80, and the chance of experiencing a second seizure is between 40% and 50%. In many areas of the world, those with epilepsy either have restrictions placed on their ability to drive or are not permitted to drive until they are free of seizures for a specific length of time. The word epilepsy is from Ancient Greek ἐπιλαμβάνειν, 'to seize, possess, or afflict'.

Signs and symptoms

Epilepsy is characterized by a long-term risk of recurrent seizures. These seizures may present in several ways depending on the part of the brain involved and the person's age.

Seizures

The most common type (60%) of seizures are convulsive. Of these, one-third begin as generalized seizures from the start, affecting both hemispheres of the brain. Two-thirds begin as focal seizures (which affect one hemisphere of the brain) which may then progress to generalized seizures. The remaining 40% of seizures are non-convulsive. An example of this type is the absence seizure, which presents as a decreased level of consciousness and usually lasts about 10 seconds.

Focal seizures are often preceded by certain experiences, known as auras. They include sensory (visual, hearing, or smell), psychic, autonomic, and motor phenomena. Jerking activity may start in a specific muscle group and spread to surrounding muscle groups in which case it is known as a Jacksonian march. Automatisms may occur, which are non-consciously-generated activities and mostly simple repetitive movements like smacking of the lips or more complex activities such as attempts to pick up something.

There are six main types of generalized seizures: tonic-clonic, tonic, clonic, myoclonic, absence and atonic seizures. They all involve loss of consciousness and typically happen without warning.

Tonic-clonic seizures occur with a contraction of the limbs followed by their extension along with arching of the back which lasts 10–30 seconds (the tonic phase). A cry may be heard due to contraction of the chest muscles, followed by a shaking of the limbs in unison (clonic phase). Tonic seizures produce constant contractions of the muscles. A person often turns blue as breathing is stopped. In clonic seizures there is shaking of the limbs in unison. After the shaking has stopped it may take 10–30 minutes for the person to return to normal; this period is called the "postictal state" or "postictal phase." Loss of bowel or bladder control may occur during a seizure. The tongue may be bitten at either the tip or on the sides during a seizure. In tonic-clonic seizure, bites to the sides are more common. Tongue bites are also relatively common in psychogenic non-epileptic seizures.

Myoclonic seizures involve spasms of muscles in either a few areas or all over. Absence seizures can be subtle with only a slight turn of the head or eye blinking. The person does not fall over and returns to normal right after it ends. Atonic seizures involve the loss of muscle activity for greater than one second. This typically occurs on both sides of the body.

About 6% of those with epilepsy have seizures that are often triggered by specific events and are known as reflex seizures. Those with reflex epilepsy have seizures that are only triggered by specific stimuli. Common triggers include flashing lights and sudden noises. In certain types of epilepsy, seizures happen more often during sleep, and in other types they occur almost only when sleeping.

Post-ictal

After the active portion of a seizure (the ictal state) there is typically a period of recovery during which there is confusion, referred to as the postictal period before a normal level of consciousness returns. It usually lasts 3 to 15 minutes but may last for hours. Other common symptoms include feeling tired, headache, difficulty speaking, and abnormal behavior. Psychosis after a seizure is relatively common, occurring in 6–10% of people. Often people do not remember what happened during this time. Localized weakness, known as Todd's paralysis, may also occur after a focal seizure. When it occurs it typically lasts for seconds to minutes but may rarely last for a day or two.

Psychosocial

Epilepsy can have adverse effects on social and psychological well-being. These effects may include social isolation, stigmatization, or disability. They may result in lower educational achievement and worse employment outcomes. Learning disabilities are common in those with the condition, and especially among children with epilepsy. The stigma of epilepsy can also affect the families of those with the disorder.

Certain disorders occur more often in people with epilepsy, depending partly on the epilepsy syndrome present. These include depression, anxiety, obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD), and migraine. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder affects three to five times more children with epilepsy than children without the condition. ADHD and epilepsy have significant consequences on a child's behavioral, learning, and social development. Epilepsy is also more common in children with autism.

Causes

Epilepsy can have both genetic and acquired causes, with interaction of these factors in many cases. Established acquired causes include serious brain trauma, stroke, tumours and problems in the brain as a result of a previous infection. In about 60% of cases the cause is unknown. Epilepsies caused by genetic, congenital, or developmental conditions are more common among younger people, while brain tumors and strokes are more likely in older people.

Seizures may also occur as a consequence of other health problems; if they occur right around a specific cause, such as a stroke, head injury, toxic ingestion or metabolic problem, they are known as acute symptomatic seizures and are in the broader classification of seizure-related disorders rather than epilepsy itself.

Genetics

Genetics is believed to be involved in the majority of cases, either directly or indirectly. Some epilepsies are due to a single gene defect (1–2%); most are due to the interaction of multiple genes and environmental factors. Each of the single gene defects is rare, with more than 200 in all described. Most genes involved affect ion channels, either directly or indirectly. These include genes for ion channels themselves, enzymes, GABA, and G protein-coupled receptors.

In identical twins, if one is affected there is a 50–60% chance that the other will also be affected. In non-identical twins the risk is 15%. These risks are greater in those with generalized rather than focal seizures. If both twins are affected, most of the time they have the same epileptic syndrome (70–90%). Other close relatives of a person with epilepsy have a risk five times that of the general population. Between 1 and 10% of those with Down syndrome and 90% of those with Angelman syndrome have epilepsy.

Acquired

Epilepsy may occur as a result of a number of other conditions including tumors, strokes, head trauma, previous infections of the central nervous system, genetic abnormalities, and as a result of brain damage around the time of birth. Of those with brain tumors, almost 30% have epilepsy, making them the cause of about 4% of cases. The risk is greatest for tumors in the temporal lobe and those that grow slowly. Other mass lesions such as cerebral cavernous malformations and arteriovenous malformations have risks as high as 40–60%. Of those who have had a stroke, 2–4% develop epilepsy. In the United Kingdom strokes account for 15% of cases and it is believed to be the cause in 30% of the elderly. Between 6 and 20% of epilepsy is believed to be due to head trauma. Mild brain injury increases the risk about two-fold while severe brain injury increases the risk seven-fold. In those who have experienced a high-powered gunshot wound to the head, the risk is about 50%.

Some evidence links epilepsy and celiac disease and non-celiac gluten sensitivity, while other evidence does not. There appears to be a specific syndrome which includes coeliac disease, epilepsy and calcifications in the brain. A 2012 review estimates that between 1% and 6% of people with epilepsy have coeliac disease while 1% of the general population has the condition.

The risk of epilepsy following meningitis is less than 10%; that disease more commonly causes seizures during the infection itself. In herpes simplex encephalitis the risk of a seizure is around 50% with a high risk of epilepsy following (up to 25%). A form of an infection with the pork tapeworm (cysticercosis), in the brain, is known as neurocysticercosis, and is the cause of up to half of epilepsy cases in areas of the world where the parasite is common. Epilepsy may also occur after other brain infections such as cerebral malaria, toxoplasmosis, and toxocariasis. Chronic alcohol use increases the risk of epilepsy: those who drink six units of alcohol per day have a 2.5-fold increase in risk. Other risks include Alzheimer's disease, multiple sclerosis, tuberous sclerosis, and autoimmune encephalitis. Getting vaccinated does not increase the risk of epilepsy. Malnutrition is a risk factor seen mostly in the developing world, although it is unclear however if it is a direct cause or an association. People with cerebral palsy have an increased risk of epilepsy, with half of people with spastic quadriplegia and spastic hemiplegia having the disease.

Mechanism

Normally brain electrical activity is non-synchronous, as neurons do not normally fire in sync with each other, but rather fire in order as signals travel throughout the brain. Its activity is regulated by various factors both within the neuron and the cellular environment. Factors within the neuron include the type, number and distribution of ion channels, changes to receptors and changes of gene expression. Factors around the neuron include ion concentrations, synaptic plasticity and regulation of transmitter breakdown by glial cells. Chronic inflammation also appears to play a role.

Epilepsy

The exact mechanism of epilepsy is unknown, but a little is known about its cellular and network mechanisms. However, it is unknown under which circumstances the brain shifts into the activity of a seizure with its excessive synchronization.

In epilepsy, the resistance of excitatory neurons to fire during this period is decreased. This may occur due to changes in ion channels or inhibitory neurons not functioning properly. This then results in a specific area from which seizures may develop, known as a "seizure focus". Another mechanism of epilepsy may be the up-regulation of excitatory circuits or down-regulation of inhibitory circuits following an injury to the brain. These secondary epilepsies occur through processes known as epileptogenesis. Failure of the blood–brain barrier may also be a causal mechanism as it would allow substances in the blood to enter the brain.

Seizures

There is evidence that epileptic seizures are usually not a random event. Seizures are often brought on by factors such as stress, alcohol abuse, flickering light, or a lack of sleep, among others. The term seizure threshold is used to indicate the amount of stimulus necessary to bring about a seizure. Seizure threshold is lowered in epilepsy.

In epileptic seizures a group of neurons begin firing in an abnormal, excessive, and synchronized manner. This results in a wave of depolarization known as a paroxysmal depolarizing shift. Normally, after an excitatory neuron fires it becomes more resistant to firing for a period of time. This is due in part to the effect of inhibitory neurons, electrical changes within the excitatory neuron, and the negative effects of adenosine.

Focal seizures begin in one hemisphere of the brain while generalized seizures begin in both hemispheres. Some types of seizures may change brain structure, while others appear to have little effect. Gliosis, neuronal loss, and atrophy of specific areas of the brain are linked to epilepsy but it is unclear if epilepsy causes these changes or if these changes result in epilepsy.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of epilepsy is typically made based on observation of the seizure onset and the underlying cause. An electroencephalogram (EEG) to look for abnormal patterns of brain waves and neuroimaging (CT scan or MRI) to look at the structure of the brain are also usually part of the workup. While figuring out a specific epileptic syndrome is often attempted, it is not always possible. Video and EEG monitoring may be useful in difficult cases.

Definition

Epilepsy is a disorder of the brain defined by any of the following conditions:

- At least two unprovoked (or reflex) seizures occurring more than 24 hours apart

- One unprovoked (or reflex) seizure and a probability of further seizures similar to the general recurrence risk (at least 60%) after two unprovoked seizures, occurring over the next 10 years

- Diagnosis of an epilepsy syndrome

Furthermore, epilepsy is considered to be resolved for individuals who had an age-dependent epilepsy syndrome but are now past that age or those who have remained seizure-free for the last 10 years, with no seizure medicines for the last 5 years.

This 2014 definition of the International League Against Epilepsy is a clarification of the ILAE 2005 conceptual definition, according to which epilepsy is "a disorder of the brain characterized by an enduring predisposition to generate epileptic seizures and by the neurobiologic, cognitive, psychological, and social consequences of this condition. The definition of epilepsy requires the occurrence of at least one epileptic seizure."

It is, therefore, possible to outgrow epilepsy or to undergo treatment that causes epilepsy to be resolved, but with no guarantee that it will not return. In the definition, epilepsy is now called a disease, rather than a disorder. This was a decision of the executive committee of the ILAE, taken because the word "disorder," while perhaps having less stigma than does "disease," also does not express the degree of seriousness that epilepsy deserves.

The definition is practical in nature and is designed for clinical use. In particular, it aims to clarify when an "enduring predisposition" according to the 2005 conceptual definition is present. Researchers, statistically-minded epidemiologists, and other specialized groups may choose to use the older definition or a definition of their own devising. The ILAE considers doing so is perfectly allowable, so long as it is clear what definition is being used.

Classification

In contrast to the classification of seizures which focuses on what happens during a seizure, the classification of epilepsies focuses on the underlying causes. When a person is admitted to hospital after an epileptic seizure the diagnostic workup results preferably in the seizure itself being classified (e.g. tonic-clonic) and in the underlying disease being identified (e.g. hippocampal sclerosis). The name of the diagnosis finally made depends on the available diagnostic results and the applied definitions and classifications (of seizures and epilepsies) and its respective terminology.

The International League Against Epilepsy (ILAE) provided a classification of the epilepsies and epileptic syndromes in 1989 as follows:

- Localization-related epilepsies and syndromes

- Unknown cause (e.g. benign childhood epilepsy with centrotemporal spikes)

- Symptomatic/cryptogenic (e.g. temporal lobe epilepsy)

- Generalized

- Unknown cause (e.g. childhood absence epilepsy)

- Cryptogenic or symptomatic (e.g. Lennox-Gastaut syndrome)

- Symptomatic (e.g. early infantile epileptic encephalopathy with burst suppression)

- Epilepsies and syndromes undetermined whether focal or generalized

- With both generalized and focal seizures (e.g. epilepsy with continuous spike-waves during slow wave sleep)

- Special syndromes (with situation-related seizures)

- Localization-related epilepsies and syndromes

This classification was widely accepted but has also been criticized mainly because the underlying causes of epilepsy (which are a major determinant of clinical course and prognosis) were not covered in detail. In 2010 the ILAE Commission for Classification of the Epilepsies addressed this issue and divided epilepsies into three categories (genetic, structural/metabolic, unknown cause) that were refined in their 2011 recommendation into four categories and a number of subcategories reflecting recent technologic and scientific advances.

- Unknown cause (mostly genetic or presumed genetic origin)

- Pure epilepsies due to single gene disorders

- Pure epilepsies with complex inheritance

- Symptomatic (associated with gross anatomic or pathologic abnormalities)

- Mostly genetic or developmental causation

- Childhood epilepsy syndromes

- Progressive myoclonic epilepsies

- Neurocutaneous syndromes

- Other neurologic single gene disorders

- Disorders of chromosome function

- Developmental anomalies of cerebral structure

- Mostly acquired causes

- Hippocampal sclerosis

- Perinatal and infantile causes

- Cerebral trauma, tumor or infection

- Cerebrovascular disorders

- Cerebral immunologic disorders

- Degenerative and other neurologic conditions

- Mostly genetic or developmental causation

- Provoked (a specific systemic or environmental factor is the predominant cause of the seizures)

- Provoking factors

- Reflex epilepsies

- Cryptogenic (presumed symptomatic nature in which the cause has not been identified)

- Unknown cause (mostly genetic or presumed genetic origin)

Syndromes

Cases of epilepsy may be organized into epilepsy syndromes by the specific features that are present. These features include the age that seizure begin, the seizure types, EEG findings, among others. Identifying an epilepsy syndrome is useful as it helps determine the underlying causes as well as what anti-seizure medication should be tried.

The ability to categorize a case of epilepsy into a specific syndrome occurs more often with children since the onset of seizures is commonly early. Less serious examples are benign rolandic epilepsy (2.8 per 100,000), childhood absence epilepsy (0.8 per 100,000) and juvenile myoclonic epilepsy (0.7 per 100,000). Severe syndromes with diffuse brain dysfunction caused, at least partly, by some aspect of epilepsy, are also referred to as epileptic encephalopathies. These are associated with frequent seizures that are resistant to treatment and severe cognitive dysfunction, for instance Lennox–Gastaut syndrome and West syndrome. Genetics is believed to play an important role in epilepsies by a number of mechanisms. Simple and complex modes of inheritance have been identified for some of them. However, extensive screening have failed to identify many single gene variants of large effect. More recent exome and genome sequencing studies have begun to reveal a number of de novo gene mutations that are responsible for some epileptic encephalopathies, including CHD2 and SYNGAP1 and DNM1, GABBR2, FASN and RYR3.

Syndromes in which causes are not clearly identified are difficult to match with categories of the current classification of epilepsy. Categorization for these cases was made somewhat arbitrarily. The idiopathic (unknown cause) category of the 2011 classification includes syndromes in which the general clinical features and/or age specificity strongly point to a presumed genetic cause. Some childhood epilepsy syndromes are included in the unknown cause category in which the cause is presumed genetic, for instance benign rolandic epilepsy. Others are included in symptomatic despite a presumed genetic cause (in at least in some cases), for instance Lennox-Gastaut syndrome. Clinical syndromes in which epilepsy is not the main feature (e.g. Angelman syndrome) were categorized symptomatic but it was argued to include these within the category idiopathic. Classification of epilepsies and particularly of epilepsy syndromes will change with advances in research.

Tests

An electroencephalogram (EEG) can assist in showing brain activity suggestive of an increased risk of seizures. It is only recommended for those who are likely to have had an epileptic seizure on the basis of symptoms. In the diagnosis of epilepsy, electroencephalography may help distinguish the type of seizure or syndrome present. In children it is typically only needed after a second seizure. It cannot be used to rule out the diagnosis and may be falsely positive in those without the disease. In certain situations it may be useful to perform the EEG while the affected individual is sleeping or sleep deprived.

Diagnostic imaging by CT scan and MRI is recommended after a first non-febrile seizure to detect structural problems in and around the brain. MRI is generally a better imaging test except when bleeding is suspected, for which CT is more sensitive and more easily available. If someone attends the emergency room with a seizure but returns to normal quickly, imaging tests may be done at a later point. If a person has a previous diagnosis of epilepsy with previous imaging, repeating the imaging is usually not needed even if there are subsequent seizures.

For adults, the testing of electrolyte, blood glucose and calcium levels is important to rule out problems with these as causes. An electrocardiogram can rule out problems with the rhythm of the heart. A lumbar puncture may be useful to diagnose a central nervous system infection but is not routinely needed. In children additional tests may be required such as urine biochemistry and blood testing looking for metabolic disorders.

A high blood prolactin level within the first 20 minutes following a seizure may be useful to help confirm an epileptic seizure as opposed to psychogenic non-epileptic seizure. Serum prolactin level is less useful for detecting focal seizures. If it is normal an epileptic seizure is still possible and a serum prolactin does not separate epileptic seizures from syncope. It is not recommended as a routine part of the diagnosis of epilepsy.

Differential diagnosis

Diagnosis of epilepsy can be difficult. A number of other conditions may present very similar signs and symptoms to seizures, including syncope, hyperventilation, migraines, narcolepsy, panic attacks and psychogenic non-epileptic seizures (PNES). In particular a syncope can be accompanied by a short episode of convulsions. Nocturnal frontal lobe epilepsy, often misdiagnosed as nightmares, was considered to be a parasomnia but later identified to be an epilepsy syndrome. Attacks of the movement disorder paroxysmal dyskinesia may be taken for epileptic seizures. The cause of a drop attack can be, among many others, an atonic seizure.

Children may have behaviors that are easily mistaken for epileptic seizures but are not. These include breath-holding spells, bed wetting, night terrors, tics and shudder attacks. Gastroesophageal reflux may cause arching of the back and twisting of the head to the side in infants, which may be mistaken for tonic-clonic seizures.

Misdiagnosis is frequent (occurring in about 5 to 30% of cases). Different studies showed that in many cases seizure-like attacks in apparent treatment-resistant epilepsy have a cardiovascular cause. Approximately 20% of the people seen at epilepsy clinics have PNES and of those who have PNES about 10% also have epilepsy; separating the two based on the seizure episode alone without further testing is often difficult.

Prevention

While many cases are not preventable, efforts to reduce head injuries, provide good care around the time of birth, and reduce environmental parasites such as the pork tapeworm may be effective. Efforts in one part of Central America to decrease rates of pork tapeworm resulted in a 50% decrease in new cases of epilepsy.

Management

Epilepsy is usually treated with daily medication once a second seizure has occurred, while medication may be started after the first seizure in those at high risk for subsequent seizures. Supporting people's self management of their condition may be useful. In drug-resistant cases different management options may be looked at including a special diet, the implantation of a neurostimulator, or neurosurgery.

First aid

Rolling people with an active tonic-clonic seizure onto their side and into the recovery position helps prevent fluids from getting into the lungs. Putting fingers, a bite block or tongue depressor in the mouth is not recommended as it might make the person vomit or result in the rescuer being bitten. Efforts should be taken to prevent further self-injury. Spinal precautions are generally not needed.

If a seizure lasts longer than 5 minutes or if there are more than two seizures in an hour without a return to a normal level of consciousness between them, it is considered a medical emergency known as status epilepticus. This may require medical help to keep the airway open and protected; a nasopharyngeal airway may be useful for this. At home the recommended initial medication for seizure of a long duration is midazolam placed in the mouth. Diazepam may also be used rectally. In hospital, intravenous lorazepam is preferred. If two doses of benzodiazepines are not effective, other medications such as phenytoin are recommended. Convulsive status epilepticus that does not respond to initial treatment typically requires admission to the intensive care unit and treatment with stronger agents such as thiopentone or propofol.

Medications

The mainstay treatment of epilepsy is anticonvulsant medications, possibly for the person's entire life. The choice of anticonvulsant is based on seizure type, epilepsy syndrome, other medications used, other health problems, and the person's age and lifestyle. A single medication is recommended initially; if this is not effective, switching to a single other medication is recommended. Two medications at once is recommended only if a single medication does not work. In about half, the first agent is effective; a second single agent helps in about 13% and a third or two agents at the same time may help an additional 4%. About 30% of people continue to have seizures despite anticonvulsant treatment.

There are a number of medications available including phenytoin, carbamazepine and valproate. Evidence suggests that phenytoin, carbamazepine, and valproate may be equally effective in both focal and generalized seizures. Controlled release carbamazepine appears to work as well as immediate release carbamazepine, and may have fewer side effects. In the United Kingdom, carbamazepine or lamotrigine are recommended as first-line treatment for focal seizures, with levetiracetam and valproate as second-line due to issues of cost and side effects. Valproate is recommended first-line for generalized seizures with lamotrigine being second-line. In those with absence seizures, ethosuximide or valproate are recommended; valproate is particularly effective in myoclonic seizures and tonic or atonic seizures. If seizures are well-controlled on a particular treatment, it is not usually necessary to routinely check the medication levels in the blood.

The least expensive anticonvulsant is phenobarbital at around US$5 a year. The World Health Organization gives it a first-line recommendation in the developing world and it is commonly used there. Access however may be difficult as some countries label it as a controlled drug.

Adverse effects from medications are reported in 10 to 90% of people, depending on how and from whom the data is collected. Most adverse effects are dose-related and mild. Some examples include mood changes, sleepiness, or an unsteadiness in gait. Certain medications have side effects that are not related to dose such as rashes, liver toxicity, or suppression of the bone marrow. Up to a quarter of people stop treatment due to adverse effects. Some medications are associated with birth defects when used in pregnancy. Many of the common used medications, such as valproate, phenytoin, carbamazepine, phenobarbitol, and gabapentin have been reported to cause increased risk of birth defects, especially when used during the first trimester. Despite this, treatment is often continued once effective, because the risk of untreated epilepsy is believed to be greater than the risk of the medications. Among the antiepileptic medications, levetiracetam and lamotrigine seem to carry the lowest risk of causing birth defects.

Slowly stopping medications may be reasonable in some people who do not have a seizure for two to four years; however, around a third of people have a recurrence, most often during the first six months. Stopping is possible in about 70% of children and 60% of adults. Measuring medication levels is not generally needed in those whose seizures are well controlled.

Surgery

Epilepsy surgery may be an option for people with focal seizures that remain a problem despite other treatments. These other treatments include at least a trial of two or three medications. The goal of surgery is total control of seizures and this may be achieved in 60–70% of cases. Common procedures include cutting out the hippocampus via an anterior temporal lobe resection, removal of tumors, and removing parts of the neocortex. Some procedures such as a corpus callosotomy are attempted in an effort to decrease the number of seizures rather than cure the condition. Following surgery, medications may be slowly withdrawn in many cases.

Neurostimulation may be another option in those who are not candidates for surgery. Three types have been used in those who do not respond to medications: vagus nerve stimulation, anterior thalamic stimulation, and closed-loop responsive stimulation.

Diet

There is promising evidence that a ketogenic diet (high-fat, low-carbohydrate, adequate-protein) decreases the number of seizures and eliminate seizures in some; however, further research is necessary. It is a reasonable option in those who have epilepsy that is not improved with medications and for whom surgery is not an option. About 10% stay on the diet for a few years due to issues of effectiveness and tolerability. Side effects include stomach and intestinal problems in 30%, and there are long-term concerns about heart disease. Less radical diets are easier to tolerate and may be effective. It is unclear why this diet works. In people with coeliac disease or non-celiac gluten sensitivity and occipital calcifications, a gluten-free diet may decrease the frequency of seizures.

Other

Avoidance therapy consists of minimizing or eliminating triggers. For example, those who are sensitive to light may have success with using a small television, avoiding video games, or wearing dark glasses. Operant-based biofeedback based on the EEG waves has some support in those who do not respond to medications. Psychological methods should not, however, be used to replace medications.

Exercise has been proposed as possibly useful for preventing seizures, with some data to support this claim. Some dogs, commonly referred to as seizure dogs, may help during or after a seizure. It is not clear if dogs have the ability to predict seizures before they occur.

There is moderate-quality evidence supporting the use of psychological interventions along with other treatments in epilepsy. This can improve quality of life, enhance emotional wellbeing, and reduce fatigue in adults and adolescents. Psychological interventions may also improve seizure control for some individuals by promoting self-management and adherence.

As an add-on therapy in those who are not well controlled with other medications, cannabidiol appears to be useful in some children. In 2018 the FDA approved this product for Lennox–Gastaut syndrome and Dravet syndrome.

Alternative medicine

Alternative medicine, including acupuncture, routine vitamins, and yoga, have no reliable evidence to support their use in epilepsy. Melatonin, as of 2016[update], is insufficiently supported by evidence. The trials were of poor methodological quality and it was not possible to draw any definitive conclusions.

Prognosis

Epilepsy cannot usually be cured, but medication can control seizures effectively in about 70% of cases. Of those with generalized seizures, more than 80% can be well controlled with medications while this is true in only 50% of people with focal seizures. One predictor of long-term outcome is the number of seizures that occur in the first six months. Other factors increasing the risk of a poor outcome include little response to the initial treatment, generalized seizures, a family history of epilepsy, psychiatric problems, and waves on the EEG representing generalized epileptiform activity. In the developing world, 75% of people are either untreated or not appropriately treated. In Africa, 90% do not get treatment. This is partly related to appropriate medications not being available or being too expensive.

Mortality

People with epilepsy are at an increased risk of death. This increase is between 1.6 and 4.1 fold greater than that of the general population. The greatest increase in mortality from epilepsy is among the elderly. Those with epilepsy due to an unknown cause have little increased risk.

Mortality is often related to: the underlying cause of the seizures, status epilepticus, suicide, trauma, and sudden unexpected death in epilepsy (SUDEP). Death from status epilepticus is primarily due to an underlying problem rather than missing doses of medications. The risk of suicide is between 2 and 6 times higher in those with epilepsy; the cause of this is unclear. SUDEP appears to be partly related to the frequency of generalized tonic-clonic seizures and accounts for about 15% of epilepsy-related deaths; it is unclear how to decrease its risk.

In the United Kingdom, it is estimated that 40–60% of deaths are possibly preventable. In the developing world, many deaths are due to untreated epilepsy leading to falls or status epilepticus.

Epidemiology

Epilepsy is one of the most common serious neurological disorders affecting about 39 million people as of 2015[update]. It affects 1% of the population by age 20 and 3% of the population by age 75. It is more common in males than females with the overall difference being small. Most of those with the disorder (80%) are in low income populations or the developing world.

The estimated prevalence of active epilepsy (as of 2012[update]) is in the range 3–10 per 1,000, with active epilepsy defined as someone with epilepsy who has had a least one unprovoked seizure in the last five years. Epilepsy begins each year in 40–70 per 100,000 in developed countries and 80–140 per 100,000 in developing countries. Poverty is a risk and includes both being from a poor country and being poor relative to others within one's country. In the developed world epilepsy most commonly starts either in the young or in the old. In the developing world its onset is more common in older children and young adults due to the higher rates of trauma and infectious diseases. In developed countries the number of cases a year has decreased in children and increased among the elderly between the 1970s and 2003. This has been attributed partly to better survival following strokes in the elderly.

History

The oldest medical records show that epilepsy has been affecting people at least since the beginning of recorded history. Throughout ancient history, the disease was thought to be a spiritual condition. The world's oldest description of an epileptic seizure comes from a text in Akkadian (a language used in ancient Mesopotamia) and was written around 2000 BC. The person described in the text was diagnosed as being under the influence of a moon god, and underwent an exorcism. Epileptic seizures are listed in the Code of Hammurabi (c. 1790 BC) as reason for which a purchased slave may be returned for a refund, and the Edwin Smith Papyrus (c. 1700 BC) describes cases of individuals with epileptic convulsions.

The oldest known detailed record of the disease itself is in the Sakikku, a Babylonian cuneiform medical text from 1067–1046 BC. This text gives signs and symptoms, details treatment and likely outcomes, and describes many features of the different seizure types. As the Babylonians had no biomedical understanding of the nature of disease, they attributed the seizures to possession by evil spirits and called for treating the condition through spiritual means. Around 900 BC, Punarvasu Atreya described epilepsy as loss of consciousness; this definition was carried forward into the Ayurvedic text of Charaka Samhita (about 400 BC).

The ancient Greeks had contradictory views of the disease. They thought of epilepsy as a form of spiritual possession, but also associated the condition with genius and the divine. One of the names they gave to it was the sacred disease (ἠ ἱερὰ νόσος). Epilepsy appears within Greek mythology: it is associated with the Moon