Vesicoureteral Reflux

Hydronephrosis

Hydronephrosis is swelling of one or both kidneys. Kidney swelling happens when urine can't drain from a kidney and builds up in the kidney as a result. This can occur from a blockage in the tubes that drain urine from the kidneys (ureters) or from an anatomical defect that doesn't allow urine to drain properly.

Hydronephrosis can happen at any age. Hydronephrosis in children may be diagnosed during infancy or sometimes during a prenatal ultrasound before the baby is born.

Hydronephrosis doesn't always cause symptoms. When they occur, signs and symptoms of hydronephrosis might include:

- Pain in the side and back that may travel to the lower abdomen or groin

- Urinary problems, such as pain with urination or feeling an urgent or frequent need to urinate

- Nausea and vomiting

- Fever

- Failure to thrive, in infants

Causes

Typically, urine passes from the kidney through a tube called a ureter that drains into the bladder, and then out of the body. But, sometimes urine backs up or remains inside the kidney or in the ureter. That's when hydronephrosis can develop.

Some common causes of hydronephrosis include:

- Partial blockage in the urinary tract. Urinary tract blockages often form where the kidney meets the ureter. Less commonly, blockages may occur where the ureter meets the bladder.

- Vesicoureteral reflux. Vesicoureteral reflux happens when urine flows backward through the ureter from the bladder up into the kidney. Typically, urine flows only one way in the ureter. Urine flowing the wrong way makes it difficult for the kidney to empty properly and causes the kidney to swell.

Less-common causes of hydronephrosis include kidney stones, a tumor in the abdomen or pelvis, and problems with nerves that lead to the bladder.

Diagnosis

Your health care provider may refer you to a doctor who specializes in conditions affecting the urinary system (urologist) for your diagnosis.

Tests for diagnosing hydronephrosis may include:

- A blood test to evaluate kidney function

- A urine test to check for signs of infection or urinary stones that could cause a blockage

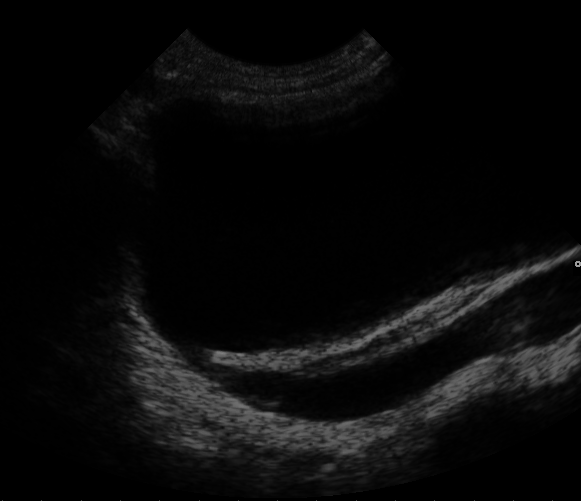

- An ultrasound imaging exam, during which your doctor can view the kidneys, bladder and other urinary structures to identify potential problems

- A specialized X-ray of the urinary tract that uses a special dye to outline the kidneys, ureters, bladder and urethra, capturing images before and during urination

If necessary, your doctor may recommend additional imaging exams, such as a CT scan or MRI. Another possibility is a test called a MAG3 scan that evaluates function and drainage in the kidney.

Treatment

Treatment for hydronephrosis depends on the underlying cause. Although surgery is sometimes needed, hydronephrosis often resolves on its own.

- Mild to moderate hydronephrosis. Your doctor may opt for a wait-and-see approach to see if you get better on your own. Even so, your doctor may recommend preventive antibiotic therapy to lower the risk of urinary tract infections.

- Severe hydronephrosis. When hydronephrosis makes it hard for the kidney to function — as can happen in more-severe hydronephrosis or in hydronephrosis that involves reflux — surgery may be recommended to fix a blockage or correct reflux.

Left untreated, severe hydronephrosis can lead to permanent kidney damage. Rarely, it can cause kidney failure. But hydronephrosis typically affects only one kidney and the other kidney can do the work for both.

Diagnosis

A urine test can reveal whether your child has a UTI. Other tests may be necessary, including:

- Kidney and bladder ultrasound. This imaging method uses high-frequency sound waves to produce images of the kidney and bladder. Ultrasound can detect structural abnormalities. This same technology, often used during pregnancy to monitor fetal development, may also reveal swollen kidneys in the baby, an indication of primary vesicoureteral reflux.

-

Specialized X-ray of urinary tract system. This test uses X-rays of the bladder when it's full and when it's emptying to detect abnormalities. A thin, flexible tube (catheter) is inserted through the urethra and into the bladder while your child lies on his or her back on an X-ray table. After contrast dye is injected into the bladder through the catheter, your child's bladder is X-rayed in various positions.

Then the catheter is removed so that your child can urinate, and more X-rays are taken of the bladder and urethra during urination to see whether the urinary tract is functioning correctly. Risks associated with this test include discomfort from the catheter or from having a full bladder and the possibility of a new urinary tract infection.

- Nuclear scan. This test uses a tracer called a radioisotope. The scanner detects the tracer and shows whether the urinary tract is functioning correctly. Risks include discomfort from the catheter and discomfort during urination.

Grading the condition

After testing, doctors grade the degree of reflux. In the mildest cases, urine backs up only to the ureter (grade I). The most severe cases involve severe kidney swelling (hydronephrosis) and twisting of the ureter (grade V).

Treatment

Treatment options for vesicoureteral reflux depend on the severity of the condition. Children with mild cases of primary vesicoureteral reflux may eventually outgrow the disorder. In this case, your doctor may recommend a wait-and-see approach.

For more severe vesicoureteral reflux, treatment options include:

Medications

UTIs require prompt treatment with antibiotics to keep the infection from moving to the kidneys. To prevent UTIs, doctors may also prescribe antibiotics at a lower dose than for treating an infection.

A child being treated with medication needs to be monitored for as long as he or she is taking antibiotics. This includes periodic physical exams and urine tests to detect breakthrough infections — UTIs that occur despite the antibiotic treatment — and occasional radiographic scans of the bladder and kidneys to determine if your child has outgrown vesicoureteral reflux.

Surgery

Surgery for vesicoureteral reflux repairs the defect in the valve between the bladder and each affected ureter. A defect in the valve keeps it from closing and preventing urine from flowing backward.

Methods of surgical repair include:

- Open surgery. Performed using general anesthesia, this surgery requires an incision in the lower abdomen through which the surgeon repairs the problem. This type of surgery usually requires a few days' stay in the hospital, during which a catheter is kept in place to drain your child's bladder. Vesicoureteral reflux may persist in a small number of children, but it generally resolves on its own without need for further intervention.

-

Robotic-assisted laparoscopic surgery. Similar to open surgery, this procedure involves repairing the valve between the ureter and the bladder, but it's performed using small incisions. Advantages include smaller incisions and possibly less bladder spasms than open surgery.

But, preliminary findings suggest that robotic-assisted laparoscopic surgery may not have as high of a success rate as open surgery. The procedure was also associated with a longer operating time, but a shorter hospital stay.

-

Endoscopic surgery. In this procedure, the doctor inserts a lighted tube (cystoscope) through the urethra to see inside your child's bladder, and then injects a bulking agent around the opening of the affected ureter to try to strengthen the valve's ability to close properly.

This method is minimally invasive compared with open surgery and presents fewer risks, though it may not be as effective. This procedure also requires general anesthesia, but generally can be performed as outpatient surgery.

Treatment of vesicoureteral reflux at Mayo Clinic is unique in its individualized approach to medical care. Cases of reflux aren't all the same. Mayo Clinic's pediatric urologists emphasize a thorough medical history and exam to fit each patient and family.

Because bowel and bladder dysfunction can have a significant impact in some patients with recurring urinary tract infections with or without reflux, Mayo Clinic has a state-of-the-art pelvic floor rehabilitation and biofeedback program to help cure these conditions.

When surgery is necessary, your Mayo Clinic care team implements a surgical plan designed to give the best results with the least invasive method. Mayo Clinic physicians are innovators of the hidden incision endoscopic surgery (HIdES) procedure, which allows for surgery to be done with incisions that aren't visible if the child wears a bathing suit.

Lifestyle and home remedies

Urinary tract infections, which are so common to vesicoureteral reflux, can be painful. But you can take steps to ease your child's discomfort until antibiotics clear the infection. They include:

- Encourage your child to drink fluids, particularly water. Drinking water dilutes urine and may help flush out bacteria.

- Provide a heating pad or a warm blanket or towel. Warmth can help minimize feelings of pressure or pain. If you don't have a heating pad, place a towel or blanket in the dryer for a few minutes to warm it up. Be sure the towel or blanket is just warm, not hot, and then place it over your child's abdomen.

If bladder and bowel dysfunction (BBD) contributes to your child's vesicoureteral reflux, encourage healthy toileting habits. Avoiding constipation and emptying the bladder every two hours while awake may help.

Preparing for your appointment

Doctors usually discover vesicoureteral reflux as part of follow-up testing when an infant or young child is diagnosed with a urinary tract infection. If your child has signs and symptoms, such as pain or burning during urination or a persistent, unexplained fever, call your child's doctor.

After evaluation, your child may be referred to a doctor who specializes in urinary tract conditions (urologist) or a doctor who specializes in kidney conditions (nephrologist).

Here's some information to help you get ready, and what to expect from your child's doctor.

What you can do

Before your appointment, take time to write down key information, including:

- Signs and symptoms your child has been experiencing, and for how long

- Information about your child's medical history, including other recent health problems

- Details about your family's medical history, including whether any of your child's first-degree relatives — such as a parent or sibling — have been diagnosed with vesicoureteral reflux

- Names and dosages of any prescription and over-the-counter medications that your child is taking

- Questions to ask your doctor

For vesicoureteral reflux, some basic questions to ask your child's doctor include:

- What's the most likely cause of my child's signs and symptoms?

- Are there other possible causes, such as a bladder or kidney infection?

- What kinds of tests does my child need?

- How likely is it that my child's condition will get better without treatment?

- What are the benefits and risks of the recommended treatment in my child's case?

- Is my child at risk of complications from this condition?

- How will you monitor my child's health over time?

- What steps can I take to reduce my child's risk of future urinary tract infections?

- Are my other children at increased risk of this condition?

- Do you recommend that my child see a specialist?

Don't hesitate to ask additional questions that occur to you during your child's appointment. The best treatment option for vesicoureteral reflux — which can range from watchful waiting to surgery — often isn't clear-cut. To choose a treatment that feels right to you and your child, it's important that you understand your child's condition and the benefits and risks of each available therapy.

What to expect from your doctor

Your child's doctor will perform a physical examination of your child. He or she is likely to ask you a number of questions as well. Being ready to answer them may reserve time to go over points you want to spend more time on. Your doctor may ask:

- When did you first notice that your child was experiencing symptoms?

- Have these symptoms been continuous or do they come and go?

- How severe are your child's symptoms?

- Does anything seem to improve these symptoms?

- What, if anything, appears to worsen your child's symptoms?

- Does anyone in your family have a history of vesicoureteral reflux?

- Has your child had any growth problems?

- What types of antibiotics has your child received for other infections, such as ear infections?